Kharkiv

A Kidnapped Ukraine Or Why It Is Good To Be Radical

Publication: 8 May 2023

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESWe, the Central Europeans, were the quickest to see through it. And at the same time, a further task is facing us. For it is a good thing that alongside Ukraine as a political reality and sovereign state, its culture is increasingly mentioned in the international circulation and in the media.

From the perspective of history, thirty years is not much, although from the perspective of someone’s life it is quite a lot. I was fortunate to have been born in that part of “Eastern Europe” where parting with communism was done very gently, and I grew up in a time of vanishing borders. Nevertheless, the bloody scenes of Bucharest in 1989 and later the several-years-long drama of the former Yugoslavia made me immune to illusions.

Russia, as we all know, is like a matrioshka. Once the Soviet layer was shattered, a blushing babushka appeared, greeted with some relief by the so-called “mature democracies”. In polite company it was inappropriate to ask: “Why do you have such big eyes? Why do you have such teeth?” On a more serious note, we were wrong to assume that the Autumn of Nations had passed. In fact, only the first act was behind us. Now the second act is playing out. Because from the perspective of history, thirty years is not much to do away with the structures of evil.

When the babushka took off her kerchief in February 2022, we saw the phantom of an empire that had by no means passed into history, and at the same time it became clear how much had been done over the past thirty years to make us, Europeans, justify its existence in our heads again. Today we already realise that the disarmament of the empire from our imagination is as important as the military arming of the defenders of Ukraine. The task for us, people of culture, is precisely the former.

One toxic mystification is the notion of a “great” Russian culture, without which the European heritage supposedly remains incomplete.

A few days after the outbreak of the war, a Polish writer blithely confessed that he would gladly shoot the Russians who invaded Ukraine, but that he would not for anything in the world give up his engagement with the great Russian culture, because he would be doing himself a disservice.

Three months later, in May, on the seventieth day of the war, maestro Daniel Barenboim, most eminent Berlin conductor, spoke out. He lamented the boycott of Russian music on Polish stages. A conductor friend lamented to him that he couldn’t even conduct Tchaikovsky’s “Third Symphony” in Katowice, which the gracious composer had, after all, subtitled “Poland”. “It’s grotesque and even stupid,” he rebuked us Poles. The maestro confused boycott with silence to honour the victims. And the more victims, the longer the silence lasts.

What puzzled me, however, was why the absence of Russian music bothered the conductor so much. Why were no other composers able to soothe him? Let’s say: Dvořák, Janáček, Bartók, Szymanowski, Enescu… Why was the absence of Russian repertoire a blow to European stages, while none of the great stars shed tears over the underperformed Polish, Czech, Lithuanian, or Romanian music?

The surprising answer came a month later from St. Petersburg. Mikhail Piotrovsky, director of the Hermitage, said in a now famous interview that Russian culture was even more European than the cultures of some European countries, such as Norway! That Russia’s European traditions dated back to antiquity, as evidenced by monuments in the south – in Crimea! I was quite incredulous, for he was talking about the monuments stolen from Ukraine, the whole forcibly seized chunk of it. But I should not have been surprised, because such are the rules of imperial culture, which appropriates and disowns, seeing nothing wrong with it; which ruthlessly colonises, and annihilates the insubordinate.

However, there is a difference between old and contemporary imperialism, namely today’s empires establish their rule primarily over people’s imagination, and unfortunately they use culture as their weapon.

Take a look at Wikipedia. Admittedly, the Russian language makes a distinction between the terms “russkij” and “rossijskij”, distinguishing nationality from citizenship, but who would bother with that! In the Russian-language version, Georgia’s greatest artist, Niko Pirosmani, is a Russian artist, which he neither was, nor wanted to be, nor even could have been, because he never as much as went outside Tbilisi. The authors of Russian entries about Ilya Riepin or Nikolai Gogol, who were born near Poltava and Kharkiv, are also quite unequivocal, even if the author of “Dead Souls” once confessed that he himself did not know what kind of soul he had…

Such “nuances” have been exposed for years by Mykola Ryabchuk, patiently explaining that individually they seem insignificant, but as a whole they present a false picture – less favourable for Georgia or Ukraine, but always favourable for Russia.

In the empire, the rule was simple. Anyone could make the upward climb in the social hierarchy of either Czarist Russia or the Soviet Union, provided he became a Russian. If he insisted on his Georgianness, Lithuanianness, or Ukrainianness, he was doomed to stay on the sidelines.

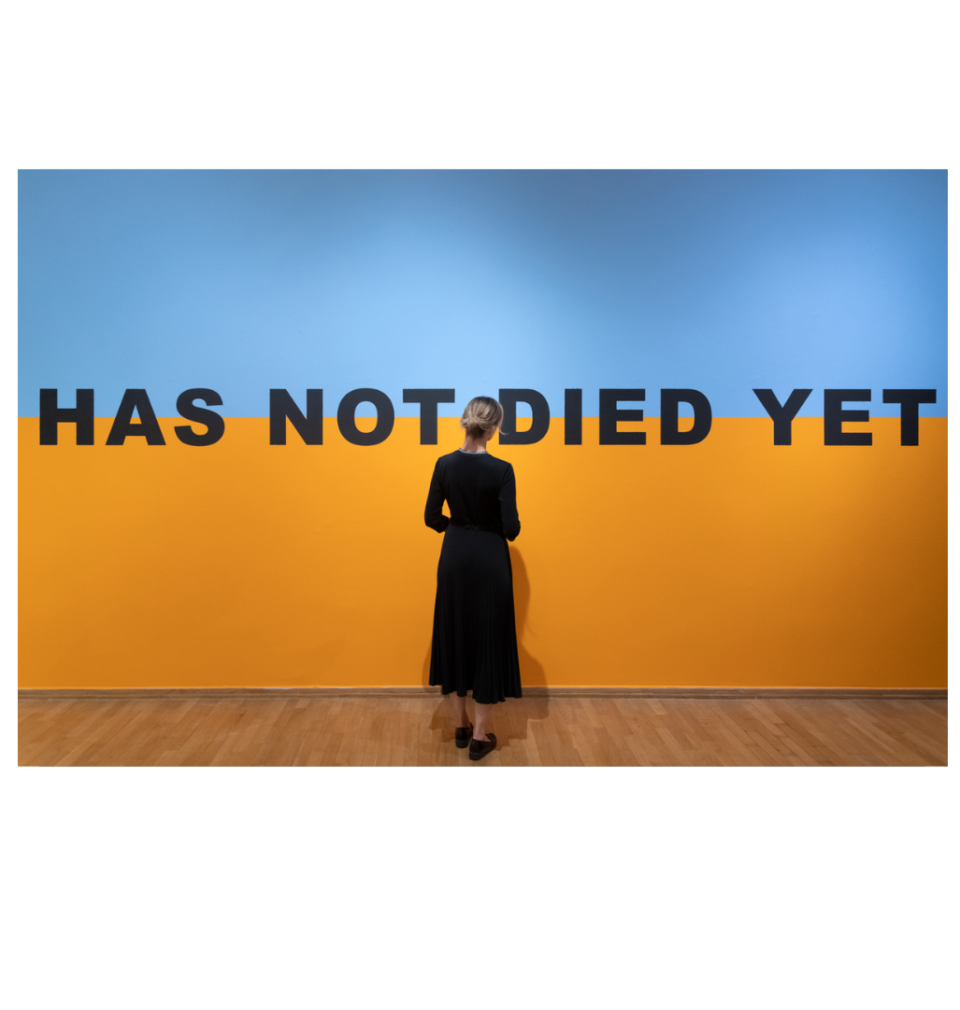

At the same time, in Ukraine, the Russians carried out cultural purges every few decades. In the 1920s, they launched a revival of native culture in Kharkiv to gain support for the new Soviet government. The city flourished as a centre of Ukrainianness. For a short time. Moscow quickly changed course. To this day, it is not known how many artists were killed then. The conspiracy of silence about the “murdered revival” continued throughout communism. The 1960s saw another wave of repression, this time against a generation of artists and intellectuals known as “Shestydesiatnyks”, simply because they had claimed the right to the Ukrainian language and culture in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Twenty years later, the same thing happened to the founders of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group – exile for them and persecution for their families.

The matter was easy for the Soviets insofar as they simply expanded the tools used by their predecessors. Take, for example, the infamous 1876 Ems ukaz, in which Tsar Alexander II forbade the use of Ukrainian and the name “Ukraine” in print. This is one of the reasons explaining why Ukrainians did not produce their Pushkin, Tolstoy, or Dostoevsky, so revered by Europeans. They did not have universally recognised classics whose reputation could serve contemporary Ukrainian writers or painters. Ironically, today the situation is reversed. It is contemporary Ukrainian artists who are working to bring their classics into European culture, to show the world the doomed heritage that shaped Ukraine.

Of course, I know the claim that Russian artists were not to blame. After all, Shostakovich, Mandelstam, or Brodsky struggled against the regime’s oppression. They were harassed or murdered by their own state. This is true, and this is why Ukrainians fight for their state, because it will protect them even if it is imperfect, while Russia never does. Russia doesn’t change its methods, only adapts them to the circumstances. It tolerated Ukrainians, Oksana Zabuzhko says, as long as they meekly played the role of donor to Russian culture. But they faced firm opposition whenever they wanted independence and distinctiveness of their culture and history. On the one hand, Russia made sure that the world did not learn about the world-class achievements of Ukrainian culture. On the other hand, it has invested in the promotion of its “great” culture as if it provided immunity, knowing Europe’s helplessness in the face of a puzzle containing both “great” artworks and crimes.

We, the Central Europeans, were the quickest to see through it. And at the same time, a further task is facing us. For it is a good thing that alongside Ukraine as a political reality and sovereign state, its culture is increasingly mentioned in the international circulation and in the media. But until we really support Ukrainians in telling the world about their culture, the notion of one “great” culture and some minor cultures will persist. Do we need to be reminded that in the last century many Western universities relegated Polish studies, Bohemian studies, or Lithuanian studies to the faculties of Sovietology? So it’s high time to liberate Ukrainians (and the free Belarusians) from the Russians once and for all. First in people’s heads. Otherwise, every now and then you’ll find Europeans talking about a “Russian sphere of influence” or a “tussle between two Slavic peoples”. Some people are still surprised by the Ukrainians’ reluctance to be a brotherly nation to the Russians. They don’t quite accept that Ukrainians have a separate culture, a separate historical tradition and their own identity. Sometimes we are surprised by people who can hardly be suspected of bad intentions. Watching Ukrainians bravely fend off the Russian invasion, the prominent European intellectual, Bulgarian Ivan Krastev, wrote of an “unexpected nation” that revealed itself in particular upheavals: during successive Maidans or during the current war. While it is true that such tragic moments provide the nation with its most enduring myths – the famous response of Ukrainian soldiers to the Russian warship crew has already gone down in history – the idea of Ukrainians appearing out of nowhere is a clear sign of ignorance. Therefore, countering ignorance, explaining the peculiarities of our part of the continent has again become a primary task for Central European intellectuals and for our institutions. We are aware of this at the International Cultural Centre.

We spoke about the fact that Ukrainians as an imagined community had been shaping themselves for more than two centuries, for example, in 2015, shortly after the war in eastern Ukraine began and when Russia occupied Crimea. We spoke about it at the “Myth of Galicia” exhibition, showing how this now-defunct Austro-Hungarian land became the laboratory of the modern Ukrainian nation. However, we have long held the belief that there was no single Ukraine. Instead, there was a state composed of poorly matched parts. We were wrong.

If Ukraine had been a homogeneous whole over such a large territory, it would have fit perfectly with Putin’s archaic notions of “little Russia”. The paradox is that the linguistic, ethnic, and religious homogeneity to which we have become accustomed in our Central European countries was for many years regarded by Ukrainians as the ideal to which they should aspire. But heterogeneity and diversity proved to be their strength and salvation, the source of something unique and salutary. In spite of the voices bemoaning the dysfunctionality of the state, the war showed that while Ukraine is indeed fragmented, it is not divided. This is both a paradox and its greatest success. And we all remain impressed by Ukraine’s ability to coexist over and above differences.

We became convinced of this just before the war. In the year of the thirtieth anniversary of independent Ukraine, we prepared in the ICC Gallery an exhibition of its art of the last two hundred years, based on the collection of the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. And we saw with our own eyes a multifarious Ukraine: national, folk, Soviet, Slavic, Oriental, Central European, Cossack-independent, local and global, old-fashioned and modern. We saw Ukraine searching for its own face, tearing off the masks that one system after anothermade it wear for decades. A remarkable self-portrait.

A month after the exhibition ended, Russia attacked Ukraine.

However, let’s travel back some thirty years in our heads.

It would not have been possible to disarm the Soviet empire so successfully had it not been for Kundera’s “magic formula”, the concept of “a hijacked West”, invented by intellectuals and artists in the 1980s. To paraphrase Havel, it was “the power of the powerless”, allowing the lack of real power to be compensated by a superior imagination in the struggle against the empire. The formula was relatively simple, based on the rhetoric of reminding Western Europeans of a part of Europe they had overlooked and arousing in them a sense of obligation. Central Europe spoke the language of values. It was dissident, liberatory. It worked brilliantly.

In essence, it was aimed not so much at the Soviets as at something Western Europeans had inscribed in their minds some two hundred years ago, through a “philosophical geography” created by the enlightened to deliberately control the continent. It was neither about actual conquest nor real knowledge, but about dividing Europe according to perceptions and values, ideas and preferences. The West was imagined as the source of civilisation, and the Orient as something irresistibly alien to it, and the European East, neither Western nor alien, but certainly backward, was placed between the two. The Balkans were also invented as the opposite of rational Europe, the irrational child of “sick” Turkey. The figure of a flourishing Europe became the anecdotal garden of Metternich, the Austrian chancellor thinking of himself as a conductor in a concert of powers. The wild foothills of Asia stretched beyond the fence of this garden. When Stalin had to be appeased after World War II, ceding him this “inferior” part, the East with the Balkans, did not seem a loss. Metternich’s picket fence was replaced in Western minds by an iron curtain.

The tale of the “hijacked West” thus acted as a pang of conscience. The Europeans rushed to support their “Central” brothers in freeing themselves from the yoke of communism. Unfortunately, having fulfilled its romantic task, the idea of Central Europe became handy in day-to-day politics. It was impossible for everyone to enter the “garden” of the European Union all at once. Therefore, in our own backyard, we recreated the same categories – the division into more “like us” and more “alien”, i.e. “Central” and “Eastern”, the latter being “less civilised”. The idea of Central Europe gradually disappeared from the intellectual horizon. Did we betray the Centre, just as the West had once betrayed it? Did we trade values for interests? Did we reduce Central Europe to a nice formula of cross-border cooperation and only now has the “sadness of Visegrad” looked into our eyes? Ukrainian intellectuals have been posing these unpleasant questions to us for some time. They wanted to believe that Central Europe did not simply dissolve, but drifted towards Ukraine. I think the most sincere defence of it was the sober perspective of the said Mykola Ryabchuk, his honest dissection of Central European messianism. Three decades after Kundera, he showed in his essays how the idea of a “hijacked West” was salutary for Central Europe, but disastrous for Eastern Europe. How we learned not to tear down walls, but to push them further east.

With vague offers of the Eastern Partnership or the Western Balkans format, we assuaged our pangs of conscience, while the empire imperceptibly rebuilt its sphere of influence, anaesthetising Europeans with the opium of its “great” culture. As in Voltaire’s time, we again liked the beardless boyars on luxury yachts or in the elegant apartments of Londongrad. Many also admired the “enlightened autocrat” himself.

Today, Ukrainians are fighting on both fronts. On the ground and in the imagination. In the latter, we were also under occupation.

If we are to have an impact, we must be radical. Otherwise, we will become a cursed place again, “bloodlands”, a perpetual “borderland on fire”. Therefore, let’s welcome Ukraine into the European Centre without delay. In language, in culture, in the way we think about it. Let’s start talking about Ukrainian culture as one of the Central European cultures. Let’s hijack it from the “East”, from the imperial “shadow-line” at all levels of imagination. Such a reconstruction of the Centre is needed both for Ukraine and for us.

The text is based on a speech delivered at the seminar “Central European Institutions, New Worlds and Old Mythologies” organised in September 2022 by the Central European Forum Olomouc (SEFO).

Copyright © Herito 2020