Austria

I feel more like a citizen of Mitteleuropa

Publication: 20 January 2025

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESMartin Pollack talk to Jacek Purchla

After World War I, Austrians woke up in a tiny country, and perhaps that’s how they came to doubt whether we could even survive as a nation, as a state – and this conviction stayed with us for a very long time.

Jacek Purchla: What does it mean to you to be Austrian?

Martin Pollack: Nowadays, being Austrian, Swiss, or German, is normal. However, twenty or thirty years ago it was not so obvious. Back then, it was up for dispute whether such an ideological oddity and a European bastard that is Austria exists at all. I grew up surrounded by friends and family who believed it not to be the case. My grandmother, a Nazi supporter, always used to say: “You aren’t Austrian, you’re German. Your father was German, your favourite grandfather was German, we’re all Germans.”

After World War I, Austrians woke up in a tiny country, and perhaps that’s how they came to doubt whether we could even survive as a nation, as a state – and this conviction stayed with us for a very long time. In the right-wing circles, always numerous in Austria, it is said to this day that while we have the Austrian state, there is no Austrian nation, just like there is no Austrian culture, for the culture here was almost exclusively Jewish. They feel German. But now, it’s changing. So is my perspective, as now I often visit the countryside.

In Burgenland.

Yes, not far from the Hungarian and Slovenian borders. The little Kakania. The man who helps me in my garden is Slovenian, and our housekeeper comes over from Hungary. It’s very convenient: they are happy with the wages, and we get to feel the world remains open. Even though the situation in Hungary and Slovenia does not look very optimistic, and Austria isn’t as open as it used to be.

Can you confirm that Toni Sailer – known as the Black Lightning Bolt – along with the sports scene of the 1950s and 1960s and the Innsbruck Winter Olympics, which I can remember well, helped create the modern Austrian identity? After all, when it came to building national pride, sport was just as important as literature, especially that of Peter Handke, Elfriede Jelinek, and you. All of this strengthens the autonomous Austrian identity.

That’s what makes for the process of normalisation: today, we no longer ask whether we are a nation or not. We are no longer bothered by the Hungarian and Croatian minorities in Burgenland, or by the Slovenian minority in Carinthia.

You live by Lake Neusiedl. One could say the Republic of Austria stretches between two lakes: Neusiedl and Bodensee. In the middle, there lies a land of remarkable geographic and natural diversity. Does it mean the nation inhabiting it cannot see this diversity, or is there some distinguishable difference, such as that of mentality, between Vorarlberg and Burgenland?

I come from Upper Austria and it means a lot. I remember that back at school, we found other people’s origins important: whether they’re Tyrolean or Carinthian. Of course, the difference was audible. To this day, I can recognise a Tyrolean accent.

Over the past 50 years, an Austrian nation in the Austrian state was born. The Republic is now over a hundred years old and yet, the diversity of its regions was preserved.

Yes, absolutely.

How much does the heritage of Kakania mean to the Republic of Austria in 2021, also in the political sense?

Sadly, not that much. Of course, the myth of Kakania is used in tourism: Hofburg, Sisi, Francis Joseph, and so on. We are very proud of our heritage and keen to showcase it. In the past, especially in the 1960s, we used to make a lot of movies about this moment in our history, it was a popular and marketable topic back then. Today, however, it’s no longer present in the culture.

And how about young Austrian, 18- or 19-year-old high school graduates: does the monarchic heritage mean more to them?

In Austria, we know very little about our neighbours. Be it Czechs, Hungarians, or Slovenians, that’s no different to us: Austria is not interested in this topic at all. There are economic partnerships in place but not much is happening on the cultural level. I have always been the one to encourage the exploration of Polish or Ukrainian literature, with little success. There aren’t many translations from those languages being published, either. In Austria, an average radio or TV journalist can’t pronounce a Polish, Hungarian, or Slovenian name. Take yours. Translator Jacek Stanisław Buras used to live in Vienna for years. My publisher knew him very well, and yet he still doesn’t know how to say his name right. I find it very sad.

You have also confirmed the rather obvious political thesis: Austria chose the West. The country joined the European Union quite late, in the mid-90s, and after the fall of the Iron Curtain, it had a choice, as Erhard Busek pointed out. Before, there was the Mitteleuropa plan that entailed establishing Austria’s political position as a leader who would rebuild the relationships all the way to the Adriatic and Galicia. The phase of Alois Mock and the early 90s Busek was replaced with Austria’s readiness to bring in Brussels, Europe, and oblivion to both viribus unitis and the late 19th-century family.

Unfortunately so, and it is done on purpose. Here, people destroy their heritage on purpose, and oftentimes, it can be noticed even in their names.

Blecha, Sekanina. I remember my visit to Vienna in the 1980s, I went there for a scholarship with a linguist who walked around the city, writing down Slavic names of the local storeowners. The chancellors of Austria were, one after another, Kreisky, Sinowatz, Vranitzky, and Klima.

Of course. But nowadays, more people are looking for their roots. They often contact me, aware of my knowledge of Galicia. I receive letters that say: “Dear Mr Pollack, I would like to find out where my grandfather came from.” I am now in touch with a man from Switzerland, looking for the traces of his ancestor who migrated from Galicia to Switzerland. He had very little information on his grandfather and wanted to find out whether he was Polish, Ukrainian, or German. We discovered that he was Ukrainian and came from Lipowce village in Galicia. More and more often, people want to know their heritage and understand it better. They are very keen to get in touch with people like me. Sadly, there aren’t many experts in my field, so when it comes to Galicia, they always end up knocking at my door.

Martin Pollack, he’s the one!

I tell them: Look, I’m 77 and poorly, leave me alone, it’s a closed chapter for me now. The younger generation should take over.

As you have probably guessed by now, some of my questions are meant to somewhat prod at the question of denazification. How did the Austrian readers and critics react to your brilliant book “The Dead Man in the Bunker”? Were people trying to avoid it?

I was surprised by how well it was received. Of course, from the publishing perspective, it was still a marginal book, not a mass-reader title. It seemed to me that my publisher was even more surprised – as if they expected people to start throwing stones at me. I appeared at several events in Amstetten where my grandparents come from, the Nazi-sympathising part of the family. The locals reacted in a very positive way, nobody was criticising me. In Poland, despite an equally good reception, some people were saying I should not write such things about my own family. I have never heard such comments in Austria.

Several years ago, I was an expert at the European Commission, working on the European Capital of Culture project when Linz was competing for the title. I know it’s your Heimat but I was shocked to see that the entire very ambitious project submitted by Linz was facing the future: new technologies in culture, and so on. Nobody mentioned the idea of making the Führer’s beloved capital a site of a great museum of masterpieces brought from all over Europe. Only after my suggestion did the programme include a whole section on the post-Anschluss period. That’s when, for the first and last time in its history, Linz was a European capital, nominated by Adolf Hitler. In my opinion, we simply couldn’t have omitted it in Linz’s submission for the European Capital of Culture project.

I have experienced it a lot. Linz features in my books, I come from Linz, and I have a strong connection to this city. I have always heard the same comments: “Why Linz again, you say it’s such an important place, and really, it’s just a provincial town.” To which I always responded in the same way: “Linz was the hometown of my stepfather who went to school with Hitler and was close to him in those years. My stepfather knew the Eichmann family well, too, and my sister used to date the son of Ernst Kaltenbrunner who was the Chief of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, Reich Security Main Office). A decent man he was, very nice indeed.” Hitler, Eichmann, Kaltenbrunner… That’s a lot for one provincial town, not to mention my father, the head of the Gestapo in Linz. This was a very important city, known as the “Patenstadt des Führers” – the Twin Town of Führers.

Nowadays, it’s changed, also thanks to the work done by a generation of the young historians and literature specialists who get it. I remember us living in the villa neighbourhood in Linz, high on the mountain slope. On my way to primary school, I would cross the park with the figure of naked Aphrodite. I found the sculpture very interesting and whenever there was nobody around, I sometimes came close to look at the nude woman. Only 10 or 15 years ago have I learned the Aphrodite was a gift to Linz from Hitler. Poor Aphrodite, she has nothing to do with Hitler, and yet she does. How did people react? They put her in a basement, and then had some pointless dispute.

I enjoy listening to Georg Kreisler; his song “Weg our Arbeit” makes a really powerful impact on me. And I cannot help but wonder how he, a Jew from Vienna, managed to enjoy such level of success in the Austrian media after 1955, having returned from emigration in America.

I don’t think they liked him very much for those songs but at the same time, Kreisler was a master of dark humour. When he wrote this song in 1968, everyone started asking their fathers and grandfathers: “And you, what were you doing back then?” “Where were you?” Kreisler made us realise Austrians weren’t so brave after all, being “Hitler’s first victim” and so on. In reality, as he sings, on our way to the office we pass by people who used to be in the SS and the Gestapo. And I have experienced it, too.

In Austria, I have been to meetings where people came up and thanked me for my book, saying it was important to them, especially if they had a grandfather serving in the SS and father in the SA. Suddenly, they realised they did know about it, just didn’t want to discuss it openly. “The Dead Man in the Bunker” showed them how to approached it calmly, with no great emotion. Kreisler also showed us it to be the Austrian normal everyday life.

In Austria, denazification was carried out quickly and haphazardly, one could hardly consider it done at all. It went somewhat better in Germany, although without severity, either. And we all have our families and friends, we know full well who did what. When I came back to Amstetten, my sweet grandmother – who loved me more than anything in the world – took me by the hand and led through the town, showing me off with pride. “Look at him, the son of my Gerhard, the brave SS-man,” she said, and everyone doted over me. It was a Nazi community. Not the lower-class, too, but the bourgeoisie.

Let’s leave that difficult part of history for now. As you have probably guessed by now, is this issue of our magazine, we would like to show Austria – perhaps not without Vienna, but not dominated by it. However, I must ask a question about Vienna, too. In the time of my youth, it was an important city: during the Cold War, Vienna was where the two world powers disputed on whether we would be killing each other with nuclear bombs or with spears and axes. Meanwhile, to us – especially to Cracovians – it was the first gate to Western civilisation and democracy. And as we began to build our democracy after 1989, the tension has deflated. In your perspective, how did the position of Vienna change since 1914? And what is Vienna today, after the fall of the Iron Curtain?

In my opinion, Vienna has somewhat lost its importance over time and it’s not such an important place anymore. We seem to be circling back to what we said at the beginning about the lost chance. Of course, we consider the West to be important to us. We are part of it without doubt, but it is very clear that we have lost our chance to strengthen our connection to the East, to our neighbours as well as to Poland or Ukraine. It’s a great loss, and Vienna has suffered the consequences, too. Interestingly, my Austrian publisher never visited the Slovakian nor Czech one, for example, even though it’s a stone’s throw away.

I can remember the 1990s, when the Austrian businesses were blocking the construction of a short piece of highway leading from Vienna to Bratislava. It came from the fear of small businesses and professionals, such as hairdressers.

Those fears are still alive today. For example, in Burgenland, they are afraid of reopening the old roads leading east that have been closed for years. The locals are afraid of competition, and they still believe the stereotype that people from the East are prone to stealing.

Every time I visited Vienna in the late 1970s and 80s, I was fascinated with the Heldendenkmal der Roten Armee memorial at Schwarzenbergplatz. After all, Vienna, Lower Austria, and Burgenland were under Soviet occupation until 1955. In the 1980s, I stayed in Vienna for a bit longer and was having my teeth fixed in a dental clinic at Schwarzenbergplatz. And there, stretched flat in the dentist’s chair, I could see the Soviet soldier through the window. Do Austrians remember the Soviet occupation today? To what extent is the Heroes Monument of the Red Army dead in the collective memory?

It is very strange, but aversion to Russia is a rarity in Austria. Our chancellor Sebastian Kurz is friends with Viktor Orbán and he insists that Putin is a great statesman, too. The Freedom Party of Austria – liberal and of Nazi origins, but is now right-wing without doubt and closely connected to Putin’s Russia. In Vienna, nobody is talking about the need for removing the Soviet soldiers memorial, nobody is protesting by it. And there is no way of pretending it’s not there. The Stalin plaque in Vienna, commemorating the place where he used to live, is another example. When my Polish friends see it, they’re confused. “Where are we?” they wonder.

The paradox is that in Poland, all the Stalin plaques were removed after 1956. In Cracow, there was a monument of Lenin and Stalin sitting on a bench in Strzelecki park. As for the collective memory of the Soviet occupation, it disappeared with the generation of the Viennese, or the inhabitants of the Lower Austria, who remembered it well. However, I do understand the dominance of political calculation that stems from economic interests.

I would also like to highlight your mission and the extraordinary role of your book To Galicia. In that period, to do so was a matter of great courage, and your work must have been quite exotic to the Austrian reader. And for that, as a Galician, I would like to thank you. And “The Emperor of Galicia” trumped even that previous achievement. You are the most notable writer to preserve and promote the history of Galicia, its myth and, should I say, the phenomenon of this region. And as such, I would like you to tell me what place Galicia occupies in the mentality of modern Austrians.

A very modest one. I remember there was a restaurant called Galicia in the Nachtsmark, and now it’s gone. Its absence feels quite symbolic, too. When I began to explore the subject of Galicia in the 1980s, people knew nothing about it. I can still remember one encounter in an antiquarian bookstore where I questioned a much older Viennese man about any books on Galicia. He showed me the Balkan aisle and instructed me to look there. I explained that I know where the Balkans are, that I studied in Sarajevo. Only later did it occur to him it might be somewhere in Poland, Ukraine… It was very typical, this first reflex of his: the Balkans. My book started the Galician wave in the German-language publishing industry. By that time, Germans became interested in this topic as well.

Did the Austrian graves in Galicia provide a bridge of sorts?

To a small extent. People don’t know much about them. When someone says their grandfather is buried somewhere there, I tell them to go and look, it’s a beautiful landscape. Those graveyards are very impressive. There is nothing quite like it anywhere else in the world, the necropolises over there were designed by incredible artists.

To me, it’s also a symbol of a civilisational level achieved by the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. During World War I, it bled. The conflict was the nail on its coffin – and at the same time, it was establishing gorgeous cemeteries for the fallen on both sides. After all, the Austrian taxpayer also covered the cost of building Orthodox graveyards for the Russian soldiers. Theirs was the unparalleled respect for death and the fallen.

It’s very important but sadly, the interest in this topic is close to none.

And what is the pride of Martin Pollack, the citizen of the Republic of Austria?

The citizen of the Republic of Austria, that sounds political. I feel more like a citizen of Mitteleuropa. I’m very glad that I get to live close to my neighbours; my Nazi family also comes from one of those countries, namely Slovenia. Nowadays, I am very closely connected to this tiny German-Slovenian town. I know the people who live there, they invite me over. We meet and look at old photographs. They are happy to have me and there is no hatred, no misunderstanding between us.

I have various Heimats, some of them Polish, too. Warsaw is my little homeland. I came to study in Poland in 1965. Back then, Poland was a strange country to me. I knew the language a little but I chose Warsaw on purpose, instead of Cracow where everyone told me to go as an Austrian. I didn’t want to explore Austrian Poland, I was after the Polish one. So I picked Warsaw during that grey but very interesting period in history. When meeting people, I could feel they are the citizens of Mitteleuropa, just like me. They had the same interests as me, they knew Austrian and German literature much better than I knew theirs, and almost all of them already had the knowledge I was yet to gain. Since that time, I am convinced that Mitteleuropa, Middle Europe, exists and is present in our hearts. It certainly has its place in mine.

Translated from the English by Aga Zano

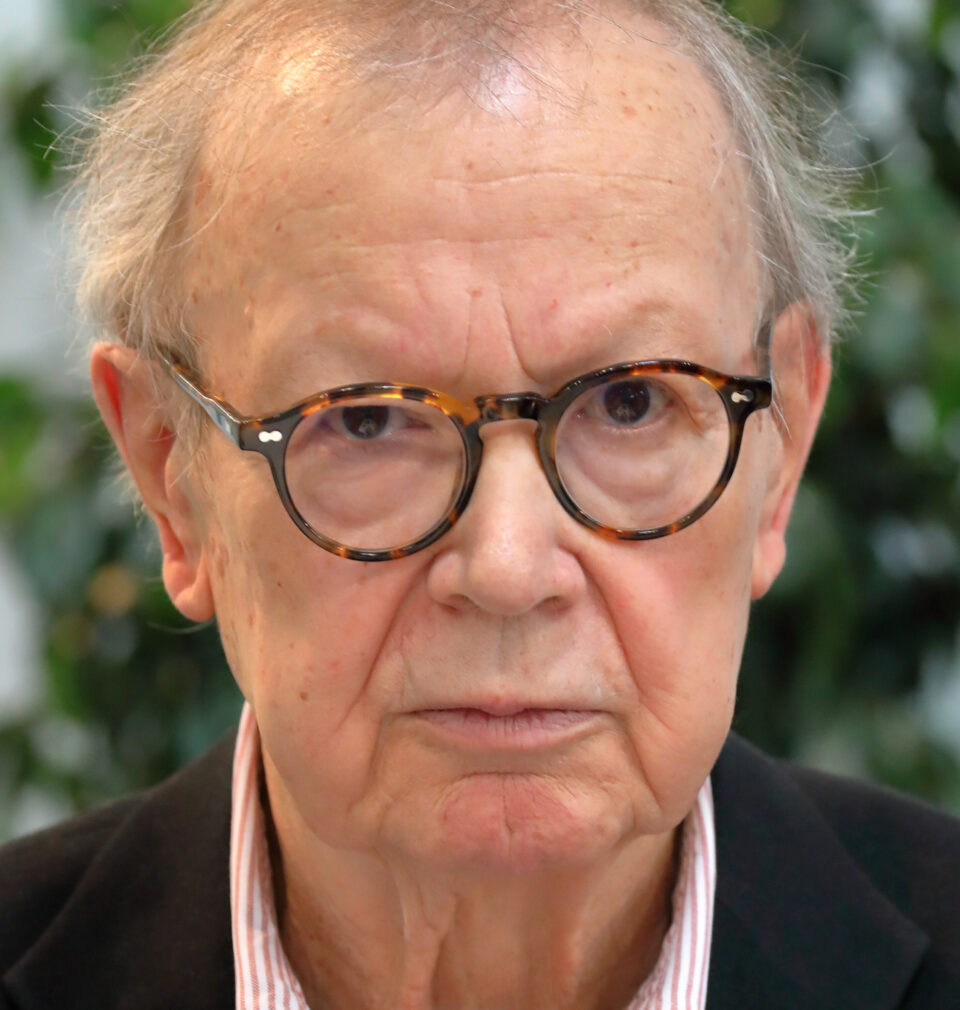

Martin Pollack (1944-2025) – translator, essayist, columnist. He studied Slavic literature and the history of Eastern Europe in Vienna and Warsaw. Until 1998, he worked as an editor and correspondent for the journal Der Spiegel. Pollack has won many prestigious awards. For the book “The Dead Man in the Bunker: Discovering My Father” he received the Angelus Central European Literary Award, for which he was again nominated for his collection of essays Topographies of Memory. He is also a laureate of the Karl Dedecius, awarded to the best translators of Polish literature into German and German into Polish, the Upper Austria Cultural Award in the field of literature, the Ryszard Kapuściński’s Translation Award for lifetime achievement in translation, and the Johann-Heinrich Merck in the field of essay writing and literary criticism. In 2017, he also received the Dialogue Award for merits in the development of Polish-German relations.

Similar articles

Copyright © Herito 2020