Borderlands

Kherson Oblast: a Liminal Being on the Land of Gods and Heroes

Publication: 16 January 2026

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESLet’s have a look at the Lower Dnipro not just as Ukraine’s gateway, but as a place connecting the locals with the world since ancient times. The Northern Black Sea region was part of common European history, complete with its mythology and heroes.

Kherson Oblast exemplifies the broader Ukrainian political landscape – for centuries, it has served as a crossroads for displaced persons and colonists. Its geography anchors key debates about the identity of this country. The Dnipro River forms a backbone for national self-understanding, the Black Sea links the region to pan-European processes, and the steppe to Eastern nomadic traditions. This fact alone makes it impossible to view Kherson outside of Ukrainian history, which is inextricably linked with Constantinople (later Istanbul). The second crucial factor in the formation of a distinctive local culture is that the Dnipro connects two different landscapes: forest and steppe, which divide the modern territory of Ukraine almost in half, into northwestern and southeastern parts.

To this day – as we see daily, if just in the headlines of news platforms – a fierce confrontation is ongoing between Russia’s neo-imperial discourse, with its powerful propaganda apparatus, and the desperate desire of Ukrainians to “reclaim” the country through its true history, which has been obscured by enemy myths. This inevitably gives rise to new mythologies. There is more than enough “myth-making” here to go around.

In 2015 together with Serhii Diachenko, an architecture historian and museum expert, we founded the Urban Re-Public NGO to explore the roots of the formation of Kherson Oblast through the lens of cultural heritage. To build a bridge between researchers and local communities, we have always engaged with young artists, practicing an anthropological approach which combines arts and ethnographic research as a means of reactivating territories whose identities seemed indistinct.

For example, in 2016 we saved the Iron Bridge in Henichesk, a city on the shores of the Sea of Azov (temporarily Russian-occupied) – a monument of engineering art, designed by a young Austrian engineer, Friedrich Roth (1878–1940), during the First World War. It is a collapsible rail bridge, which requires a minimum of assembly equipment and time, enabling swift replacement of destroyed wooden bridges. To promote his invention, Roth collaborated with the bridge construction company Waagner-Biro (then known as Anton Biró and Albert Milde & Co.; the current name has been in use since 1924). Waagner-Biro has also supplied metal constructions for iconic buildings, such as the new dome over the Bundestag, the British Museum’s courtyard roof, the Gherkin, and the Sydney Opera.

The first bridge with this design was built in Serbia in 1915 and has since been demolished. Dozens of similar bridges were built in Eastern Europe, but only a few have survived, including one in Vienna. Following the Anschluss in 1938, Nazi Germany nationalized the Waagner-Biro company and began constructing prefabricated bridges based on its designs in occupied territories. Our bridge was originally built on the Orsha River in Belarus, but was moved to Henichesk in 1951.

When local authorities announced its dismantling, activists protested, but to no avail. We brought a team of artists to support those activists through citizen-engaging artistic actions. The campaign received a nationwide response, and the bridge became a city brand.

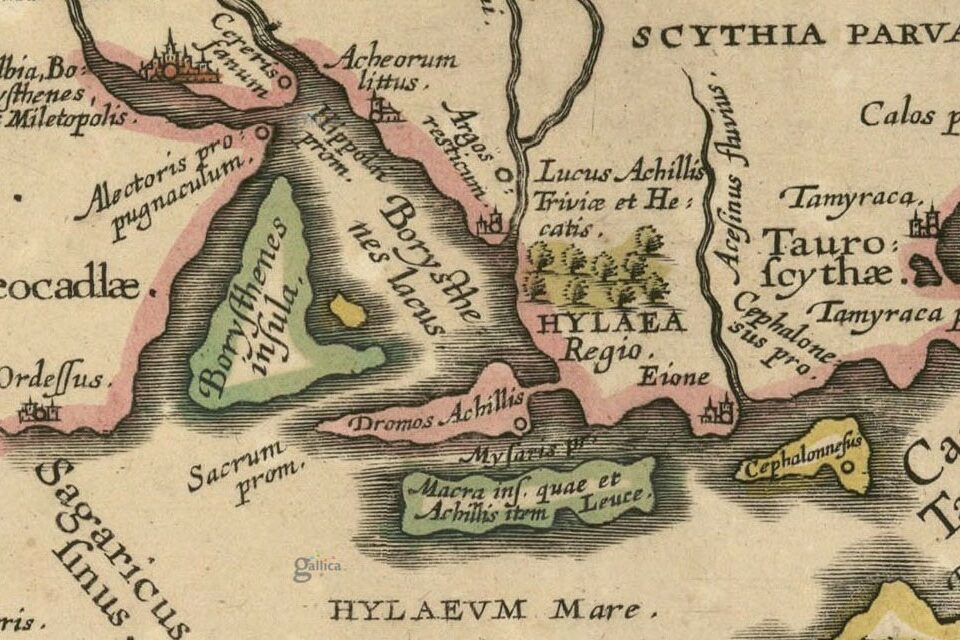

Now, let’s have a look at the Lower Dnipro not just as Ukraine’s gateway, but as a place connecting the locals with the world since ancient times. The Northern Black Sea region was part of common European history, complete with its mythology and heroes. It was here that the turbulent contact between the “Old World” and the Goths (Scandinavians) occurred, which was reflected in Scandinavian mythology. Maritime trade, primarily of grain, was at the core of these connections. Olbia, the largest ancient Greek settlement on the Black Sea coast and a national historic and archaeological reserve since 1926, was the region’s biggest grain market. This was facilitated not least by the fertile local soil. Kherson Oblast has long been considered a breadbasket, supplying Ukraine with fruits, vegetables, and melons.

Olbia was the nexus for the spread of Milesian culture, with Achilles as its patron. According to myth, he was buried on Leuke Island – now Zmiinyi (Serpent) Island in the Odesa Oblast – rising from the sea thirty-five kilometers from the Danube Delta, a rock just slightly larger than the Saxon Garden in Warsaw which controls access to Ukrainian ports and is a key element in defining Ukrainian territorial waters.

It also had a contemporary moment of glory. It was there that on 24 February 2022, when Russian occupation forces attacked with the missile cruiser Moskva, one of island’s adamant defenders, Roman Hrybov, before being captured by the occupant announced the rallying cry of this ongoing war on the radio: “Russian warship, go f…ck yourself.” This day will forever remain in the Ukrainian collective memory.

In the 4th–3rd century BC, near Kinburn Spit (Kherson Oblast), not far from where Achilles organised a famous running competition, a temple was built in his honour. A fragment of its altar is part of the Kherson History Museum. It is so heavy that the Russians failed to steal it when in the autumn of 2022 they looted the most valuable items, including Scythian gold. They also looted the Fine Arts Museum, stealing about 10,000 items from a collection of approximately 13,500 artworks. These treasures, together with rich library collections, were transported to temporarily occupied Crimea.

Antiquity stretched its long arms into the roaring 1920s, when in the village of Chornianka David Burliuk – a central figure of the Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde who claimed to be a descendant of the Zaporizhzhia Cossacks and referred to himself as a “Tatar-Zaporizhzhia Futurist” – founded the first association of Futurists, Gilea. Its members believed that Chornianka was on the edge of a wooded region of the same name, described by Herodotus in his Histories as “the first country from the sea, if you cross the Borysthenes” (that is, the Dnipro, in relation to Olbia). Thus, the Futurists connected the ancient history of the land to the future: it was here that they wrote the programmatic manifesto “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste”.

The Steppe South gave birth to the unique phenomenon of the Cossacks, with their foundations of democratic governance and armed defense of Europe’s eastern border (and the eastern ethnocultural boundary of Ukraine) on the Don River. This explains the long-standing definition of “Ukraine as a Cossack state”, even though the formation of statehood around Kyiv from the ninth century onward concerned only the northern part of Ukraine.

For communities directly on the banks of the Dnipro, the most vivid heritage is connected to the Cossacks and the Velykyi Luh (Great Meadow), home to relic forests and floodplains spanning over 400 square kilometers. The Zaporizhzhia Cossacks established winter camps in the local ravines, which were difficult for the enemy to find. “The Sich is the mother, and the Velykyi Luh is the father”, they said. Two important Sich settlements were located here: Kamianska Sich (established in 1709) and Oleshky Sich (established in 1711). In Kamianska Sich, in particular, the articles of Pylyp Orlyk’s constitution, a 1710 treaty that established a framework for an independent Ukrainian state, were discussed.

In 2022, Diachenko reconstructed the appearance of the Kazy-Kermen Fortress. The Turks built it in the late 15th century on the Dnipro River bank, at the site of the Lithuanian “Customs Post of Vytautas Magnus”, which they had seized. It also became an important crossing point on the route to Crimea. The fortress was used to attack Ukrainian lands and counter the Zaporizhzhian Cossacks, who launched raids down the Dnipro in their chaika boats. During the Crimean campaign of 1689, the Russo-Ukrainian army besieged the fortress; however, Mazepa’s Cossacks did not capture it until 1695. Fragments of the fortress have survived on the shore, bearing traces of subsequent modifications.

In 1784, the town of Beryslav was founded on the fortress’s site. Due to non-stop bombardment, it is now one of the typical cases of urbicide. In 2023, Mykolaiv-based 3D designer Oleksandr Yermolaiev created a LEGO model of the fortress based on a reconstruction as part of his series depicting historical buildings destroyed by military action.

Notably, the term “Cossack” first appears in the Codex Cumanicus within the “Kipchak–Italian Dictionary”. This lexicon was compiled in the 12th century when Venice and, later, Genoa began establishing maritime trading stations in the northern Black Sea region on the sites of ancient colonies. “Cossack” meant “a guard” or “a watch”. For such protective duties Italians typically employed local free men with military training.

Cossacks served as guards at the Dnipro crossings under the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (from 1398 onward) and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. By the late 15th century, mounting social and religious tensions had led to repeated uprisings among Ukrainian Cossacks, eventually resulting in the creation of the Cossack Hetmanate after Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s rebellion in the mid-17th century. Over the course of two centuries, until the destruction of the Cossack Host by the Russian Empire in 1775, the Sich relocated six times. However, the Velykyi Luh remained the enduring centre of the free Cossack Host’s military organisation and economic development.

The collapse of the Kakhovka dam on 6 June 2023 tragically relates to the local history of the Cossacks. It resulted in thousands of people being left homeless, and towns and villages in the Dnipro estuary getting flooded. Most of the architectural monuments in Oleshky, Hola Prystan, Zbur’ivka, and other villages, which featured interesting examples of vernacular architecture, were lost. In total, approximately 85 heritage sites were damaged. Among these losses is the nationally famous painted house of Polina Raiko in Oleshky: a naive artist who, at the age of 69, transformed her house and its outbuildings into a fresco.

However, this is far from the first time Russia has taken destructive action in this region. Between 1955 and 1958, the entire area was flooded by the Kakhovka Reservoir. At that time, the Soviet authorities also forcibly relocated people. The communists’ grandiose plans for electrification, irrigation programs, and water supply for the Crimean Peninsula were implemented in a way that easily neglected the fates of tens of thousands of people who were turned into internally displaced persons.

In the Re-Public we are currently developing a concept for the museification of Novovorontsovka village’s historical centre, which is part of the Velykii Luh. The local community harbors a bold ambition: to transform a Soviet-style museum of local history into a cultural hub and to establish an art school. Their faith in the future is strengthened by ecological wonders, such as the young willow forest that has grown on the bed of the Kakhovka Reservoir, although a toxic desert had been predicted there. It is an unexpectedly triumphant response to ecocide.

The steppe is also a significant factor in the disappearance of tangible cultural heritage. Constant wars, raids, and looting, as well as the inability to establish stable settlements over long periods of time due to climate variability, have left almost no traces of historical sites. The steppe does not permit sustainable development or settlement. All cities in the steppe region can thus be characterized as having “fragile heritage”.

The Oblast has approximately 500 relatively large settlements, each with an average of six cultural heritage sites. It so happened that the most historically precious sites were concentrated along the Inhulets and Dnipro rivers. In 2022, the front line ran along the Inhulets, and for the last two years, it has run along the Dnipro.

As of late August 2025, Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine has resulted in the destruction or damage of 1,553 cultural heritage sites. Kherson Oblast ranks second in terms of losses. We believe that the eradication of heritage may be evidence of genocidal intent. This brings to mind Thérèse Delpech’s “Savage Century: Back to Barbarism”, which is now widely quoted in the West. The author foresaw the threat posed by an aggressive Russia. The terms “rewilding” and “savage age” have become common descriptors, particularly in reference to Putin’s regime as the most horrifying “new barbarian”.

Since relocating our organisation to Odesa in the summer of 2022, we have been implementing the project “Cultural Heritage Objects of Southern Ukraine during Russia’s War Against Ukraine: Documentation, Significance, Future”, supported by the IWM. Diachenko is also an expert with the HeMo (Monitoring Heritage for Recovery) initiative. Our primary objective is to meticulously document and preserve the memory of unique cultural heritage sites across the Oblast, especially in liberated territories currently facing systematic destruction. In light of this targeted devastation, UNESCO standards for monument authenticity must evolve. Reconstructing lost sites is crucial for cultural preservation and for refuting narratives that seek to obliterate Ukraine’s past.

We, too, have shifted our focus. While many teams are documenting the loss of official heritage sites, we have begun to record landmarks that are culturally significant regardless of their official registration status. We have identified numerous sites that lack official heritage protection status, despite their deserving inclusion in the registers. Notable examples are the former Mennonite church in Mykilske (Nikolaifeld) and the Lutheran church in Vysokopillia (Kronau).

Building on this focus, in 2024 we developed the project “Cultural Heritage at the Heart of the Uniqueness and Revival of War-Torn Towns in Kherson Oblast”. The project covered the liberated territories, but to date, the entire left bank remains occupied, accounting for 74% of the oblast’s territory. We are creating lists of sites for each community to ensure they are added to state registers and included in post-war reconstruction projects. Unfortunately, this issue remains unresolved at the state level. To develop a comprehensive heritage roadmap, we are engaging a wide array of experts, including artists from Kherson, other Ukrainian cities, and abroad.

As we work on these lists, we have identified a wide range of focal points for each community in the oblast. For communities closer to the sea, notable heritage elements include those from Classical Greece. One example is the Sanctuary of Demeter in the Stanislav Cliffs over the Dnipro Estuary, near the village of Stanislav. This site resembles the American Grand Canyon in shape and was a popular tourist attraction thanks to its hiking trails. The temple, located on a cape, served as both a cult building and a lighthouse (Herodotus, Histories, IV.53). Unfortunately, part of the site has collapsed into the estuary because the cliffs are made of clay. Stanislav has endured occupation and the construction of military fortifications, and currently it is being subjected to devastating shelling from the temporarily occupied left bank of the estuary.

But we have a more optimistic story. Thanks to our initiative, the Dariivka community chose, from among the competing proposals for a new coat of arms, the image of the serpent-legged goddess Hecate (or the Scythian goddess Api), who once lived in the local caves, according to Herodotus (Histories, Book IV, Melpomene). He called her the mother of the Scythians, since the first Scythian was born to Hecate and Heracles, who came to these lands to perform his tenth labor – the capture of the cattle of Geryon. The image of Hecate-Api was borrowed from a piece of horse harness (the 4th century BC), discovered in the burial mound at 150 km from Dariivka.

Incidentally, burial mounds are a common sight in Ukraine. Three hundred and eight of them are concentrated only 40–50 km from Kherson, composing the so-called “Valley of Burial Mounds”: the only place in the country where you can stand on one mound and see dozens more around you. Moreover, you can see the steppe as our ancestors did in Scythian, Hunnic, and Polovtsian times.

Of course, performing all these activities is a tall order due to shelling from the left bank, while drones go on dropping explosives directly on people. Still, we won’t be stopped.

Consultation: Serhii Diachenko, member of ICOMOS Ukraine, member of the National Union of Architects of Ukraine, museum expert, researcher of the architecture and history of Southern Ukraine, and founder of the Urban Re-Public NGO (Kherson).

Yulia Manukian — art critic and writer contributing to Korydor, LB, Your Art, Post-impreza, and The Guardian. Curator of artistic and urban projects, including Urban Re-Public (Kherson); co-founder and editor of the platform Culture of Southern Ukraine: COYC, translator and recipient of the 2023 Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent.

Copyright © Herito 2020