Belarus

On the type of Belarusian history needed by Lukashenko’s regime

Publication: 30 March 2023

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESThe beginning of the current regime’s peculiar historical policy was marked by the presidential decree of 1995 on the withdrawal of history textbooks written after the declaration of Belarus’ independence in accordance with the national idea. The regime decided to adjust the school textbooks to Lukashenko’s historical policy, focused on integration with Russia.

When current President Alexander Lukashenko came to power in the mid-1990s, the history of Belarus became an arena of fierce political struggle. And although the regime’s preferred vision of the country’s past has undergone significant transformations over the long period of his rule, its essence has remained intact. Both the changes and constants in the image of national history convenient to those in power have repeatedly manifested themselves in the public speeches of government figures, in the publications of the state media, and in the content of historical education.

The beginning of the current regime’s peculiar historical policy was marked by the presidential decree of 1995 on the withdrawal of history textbooks written after the declaration of Belarus’ independence in accordance with the national idea. The regime decided to adjust the school textbooks to Lukashenko’s historical policy, focused on integration with Russia. For historical education, this meant a return to pro-Russian interpretations based on the models of Soviet historiography. One of their essential elements was the proclaimed existence of the Old Russian nationality, an alleged ethnicity existing in the Kievan Rus’ period from which Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians supposedly descend. The purported existence of this nationality as the common ethnic stem justified presenting the affiliation of the Belarus lands to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a violation of the unity of the East Slavs. Just as during the Soviet era, everything that could stand in the way of reunification with Russia and that moved Belarus away from the act of unification was again viewed negatively.

An extreme manifestation of Lukashenko’s pro-Russian vision of the country’s history was the so-called “new concept” of Belarusian history, developed on the President’s orders by his former teacher Yakov Trashchanka and presented in a textbook published by the latter just after 2000. He proclaimed the historical, cultural, and religious indivisibility of the East Slavic peoples from the times of Kievan Rus’; he presented the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a period of oppression of Belarusians by a “foreign power”, and the former Republic of Poland as an unviable “historical chimera”. He sought to frame the entire history of Belarus in the context of the history of Russia and Orthodoxy, and advocated the unification of East Slavic peoples in a “Great Russia” as an allied state.

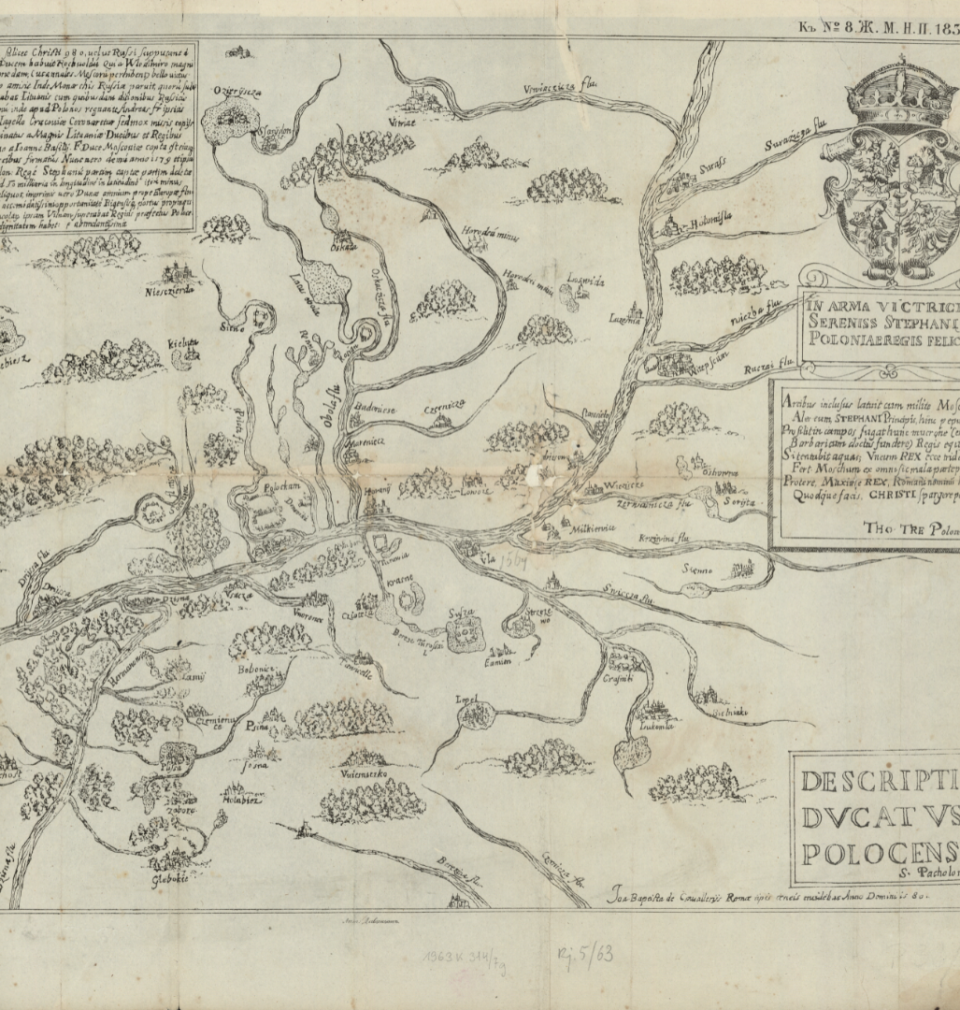

The narrative of the President’s teacher, questioning the historical and cultural independence of Belarus, fortunately did not gain traction in the educational system, and since 2009 new guidelines for “school historiography” have appeared, based on patriotic assumptions of teaching native history. The claim regarding the historical and religious unity of the East Slavic peoples since the time of Kievan Rus’ was put aside, and the reflections on “a foreign power” and the oppression of the Belarusian people in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania disappeared from the textbooks, as did the presentation of the history of Belarus in the context of Russian history. Although the Old Russian nationality was still recognised as the “foundation” of the East Slavic peoples, it was not accorded a major importance. Meanwhile, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania once again took a fundamental role in the presentation of the country’s history and appeared in a quite positive light. The new textbooks showed that the establishment of this state and its development was one of the most important chapters in the history of Belarus and that, thanks to the tolerant policy of the rulers, the Belarusian nation was formed and its culture developed. Claims of religious persecution or oppression of Belarusians in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, characteristic of the Soviet school of historiography and the first decade of Lukashenko’s rule, disappeared. Less consistent was the attitude towards the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was still associated with the processes of Polonisation and the loss of elites.

The Belarusian-centric interpretation of native history in the medieval and modern periods was in stark contrast to the presentation of the history of the 20th century, especially since the October Revolution, which was firmly stuck in Soviet patterns. For example, the textbook on 20th-century history justified everything the Bolsheviks had done, even Stalin’s crimes, and highly praised Soviet patriotism and heroism of the people during the Great Patriotic War. The regime found this textbook satisfactory and it was in use until recent times. Thus, while the interpretation of earlier periods by historians who went beyond the Soviet models gained the approval of the regime, the guidelines on recent history remained faithful to the spirit of the Soviet era.

The vision of Belarusian history expected by the regime was most explicitly promoted in the official mass media, first of all in the journal “Belaruskaia Dumka”, a monthly published by the presidential administration, which has been actively pursuing state historical policy since Lukashenko’s coming to power. The main theme of the magazine’s historical publications was and still is the Soviet era with the Great Patriotic War, although from 2007 to 2014 the editorial board also constantly turned to the distant past, addressing issues from the period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish Republic. In the latter area, there were deliberate efforts to disseminate a negative image of these polities in the consciousness of the population, reviving Russian and Soviet narratives about the national and religious oppression of Belarusians by a foreign power, etc. Lithuanian rulers, especially grand dukes Mindaugas and Vytautas, popular among the Belarusian youth, were denigrated in order to change that attitude. Claims that the Catholic Poland and the West in general were a source of danger for the Belarusians were consistently promoted, alongside the idea that the pillar of the Belarusian nation’s survival has always been the Orthodox faith, as well as kinship and close ties to Russia.

The emphasis in the official history as presented in the presidential journal suddenly shifted in 2014, after the dramatic events in Ukraine. Publications with an anti-Western bent were halted, and, more importantly, there were unprecedented attempts to prove the remote roots of Belarusian statehood (even more remote than Kievan Rus’!) and its distinctiveness. Another shift was a positive take on the non-Orthodox members of the former Belarusian elite – the Catholic nobility, etc. However, “Belaruskaia Dumka” soon abandoned references to distant times: 80 per cent of all historical publications between 2017 and 2020 were about the 20th century and usually praised the victory in the last war and the Soviet political system.

Since Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the country’s past has also been presented somewhat differently in Lukashenko’s public speeches. In a showcase speech at the official Independence Day celebrations on 1 July 2017, he presented the idea of the remote roots of Belarusian statehood, saying that its foundations had been built in the 9th century in the Principality of Polotsk, called “our historical cradle” by the President. Lukashenko added that the ancestors of Belarusians had fought “to be independent” already at this juncture. The period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was also evaluated positively – as a stage in the development of Belarusian statehood, although just a decade earlier the President had identified this state with oppression and dependence of the Belarusian people. The proclamation of the Belarusian People’s Republic in 1918, which had gone unmentioned before, also began to be seen as an important moment in the development of the state. In speeches of people representing the official point of view, the date of 25 March was analysed in the context of “the thousand-year process of the formation of the Belarusian statehood”. This liberalisation of historical policy, sanctioned by the regime, was clearly manifested in the context of the 100th anniversary of the BPR proclamation: in 2018, for the first time, a celebration of this day was allowed in Minsk, albeit in a limited form – with academic events and a large concert, but without a street parade. So we shouldn’t be surprised at the reappearance of patriotic nationalist rhetoric of statehood in official historical publications either, emphasising the priority of national values – just as in the early 1990s.

It seems that it was the war in Ukraine and external threats (from Russia) that forced Lukashenko to take historical events more seriously – as an asset used to consolidate the political unity of all citizens. The President’s words addressed to the academic community at the end of 2017 at the Second Congress of Academics of Belarus are symptomatic in this context: he called on “patriotic academics” to “defend the state” in the information warfare, and surprisingly appealed to them to unite around the national heritage; speaking on “humanistic security”, Lukashenko expressed the idea that for Belarusians, “as for any nation, one’s own history along with good traditions should become a unifying force”. The fact that the Security Council of the Republic of Belarus, in addition to the academic Institute of History, took into consideration the guidelines on politically correct history was a clear sign of the regime’s serious approach to historical issues. On what assumptions would such a history be based?

The recently published five-volume “History of Belarusian Statehood” reflects the correct image of the Belarusian past that the regime needed after Russia’s annexation of Crimea. At the very start, in the editors’ introduction to the first volume, the Belarusian nation is firmly placed among the East Slavs, who are characterised by “lack of expansionism”, “strong sense of justice”, etc. As for the Belarusian statehood, whose emergence was “inevitable”, the Principality of Polotsk was named as its beginning and considered as an “equal partner” to other state-forming centres of East Slavs such as Kiev and Great Novgorod. It is argued that this principality, unlike other Belarusian lands, did not belong to Kievan Rus’ and that led to the foundations of separate Belarusian statehood emerging in the 10th–13th centuries. Its next stage was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, created by the “ancestors of Belarusians and Lithuanians”. Such a presentation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania has become a common feature of Belarusian historiography since the early 1990s. Less typical is the recognition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a “historical stage” in the development of Belarusian statehood, even if we get the proviso that the nobles’ republic “impeded the process of Belarusian national-state development”. But then the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union are included among the “historical forms” of Belarusian statehood, which defies any comment.

The claims about the remote beginnings of Belarusian statehood are to some extent close to the assumptions of the national concept of Belarusian history from the 1990s, denounced during the first decade of President Lukashenko’s rule. However, if we take a closer look at these two concepts of historical legitimisation of a separate Belarusian statehood, we will notice significant differences. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Belarusian historiography not only tried to justify the right to independence for Belarus by linking the origins of its statehood to the Principality of Polotsk, but also rejected the unity of the East Slavic community and emphasised the participation of the Balts in the formation of the Belarusian ethnos (the issue of the Balts’ substrate). The portrayal of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a Belarusian-Lithuanian state and according this state an unquestionable role in the history of Belarus were accompanied by pushing Russia away through emphasising its negative role in the country’s past, especially through condemning the Bolshevik rule and the Soviet system. On the other hand, in the pattern constructed by the present-day regime, Belarusian statehood is based only on some ideas selected from the above. The Principality of Polotsk is regarded as its beginning, but the East Slavic unity is also paid tribute to. In the subsequent epoch, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and even the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth are given a stamp of approval, but without any criticism of Russia’s actions. As far as the 20th-century history is concerned, mainly the “positive experience” of the Soviet period is emphasised.

The main ideas about the history of Belarusian statehood are in line with the principles of the official historical policy, recently laid out in the presidential journal. The guidelines of this policy, like Stalin’s “Theses to the Main Questions of the History of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic” of 1948, automatically include among the “ways of falsifying the history of the Belarusian nation” any such acts as “denying the common roots of Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians”, talking about wars waged by Russia, “exceptionally positive interpretations of the history of the Republic of Poland” and criticising the Partitions, etc. The same is true of “creating a negative image of the Soviet past” or “stoking up the theme of political repressions of the 1920s and 1930s with the aim of denigrating the Soviet past of Belarus”.

As we can see, the current regime still needs to present the entire past of Belarus in the light of all-Russian and Soviet values, which are close to Lukashenko’s heart. Although interpretations of the remote past have evolved considerably and started to resemble the once denounced national-state concept, the official interpretation of recent history essentially continues the Moscow-centred Soviet position. We are dealing with an untruthful and artificial construct, allowing the Minsk regime to satisfy its current political needs without irritating the Kremlin. Contrary to the regime’s assurances that its historical policy will strengthen “patriotism and, consequently, the sovereignty and independence of the Republic of Belarus”, the dissemination of this version of the country’s history in fact undermines its sovereignty. For instead of consolidating the separate identity of Belarusians, it binds them to Russia (which does not recognise Belarusian independence!) and is predicated upon subsuming them in the all-Russian community.

Translated from the Polish by Tomasz Bieroń

Copyright © Herito 2020