The Invisible Power of Salt

Publication: 29 November 2022

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESTo understand how important salt was for the Transcarpathian region, all it takes is one look at its current coat of arms. It features a bear that symbolises the wild, forest-covered, impenetrable land it guards. There were never any big cities here, no industry, no advanced infrastructure.

If on the 24th of March 2021, you drove the Transcarpathian road winding by the river Tisa where it separates Ukraine from Romania, you would see a great fire. Heavy clouds of black smoke crossed borders and melted in the valleys of the Romanian Carpathians with no papers and no visas. On the Ukrainian side, two new blocks of flats were burning, with no frightened inhabitants swarming around. There were none because nobody wanted to live there. So where did the fire come from? After some research, we shall arrive at the only likely conclusion – salt. Could salt cause a fire? As it turns out, it can. It can also be the reason for building castles, setting up mines and large enterprises, bold logistic solutions, feudalist clashes, royal charters, and even wars for national independence. But let’s start from the beginning.

Solotvyno, Slatina, Salzgruben, Ocna Slatina

Salt deposits near the Transcarpathian settlement Solotvyno in Ukraine are some of the largest in the whole Carpathian region. Salt mines of similar scale and significance can only be found in Transylvania, and on the other side of the Carpathian range – in Galicia. Rock salt deposits in Solotvyno were among the most important in the former Kingdom of Hungary.

There, salt mining began long before Hungarians arrived at the Pannonian Plain. Archaeological findings prove that salt was already being extracted there in the Bronze Age. This can be proven by various artefacts from the times of the Dacian Kingdom and the Roman Empire.

In this area, salt comes up to the surface. Early on, it was extracted in a primitive fashion: saltwater was collected from the nearby lakes and holes in the ground, and then sold in kneading troughs. And since it was difficult and expensive to transport this way, people later began evaporating salt. The next step was to dig in and carve out great lumps of rock salt from the earth. Finally, technological progress advanced enough for the first underground salt mines to be set up in Solotvyno. Then, both extraction and trade soared to an industrial scale.

Thanks to the salt deposits, a settlement was set up here. It was called different names in different languages, but whatever the name, it was always salt-related. The two millennia that followed proved that salt would become the primary reason for this region to be populated and developed. And now, in the 21st century, it still affects – imperceptibly, incessantly – the lives of the residents.

The legend of Kunegunda and Wieliczka

Historians will not agree, but the local legend has it that the salt mines in Solotvyno are linked to the Polish-Hungarian princess Kunegunda. This is why the largest salt lake in the area – which emerged in the place of a former salt mine and for all means and purposes, is home to cheap local health resorts now – goes by the name Kunihunda.

The name of the princess, also known as Saint Kinga, is also connected to another important salt mine, the one in Wieliczka near Kraków. A group of historians from Uzhhorod, researching salt extractions in the region, recorded a Transcarpathian legend that explains the connection between the two deposits:

“In 1249, when Kunegunda visited the Kingdom of Hungary – rebuilt after the Mongol invasion – her father gifted her a salt mine in Maramureș. She dropped a gold ring into one of the drifts, as was customary when claiming possession, and asked for several barrels of salt to be sent to Poland. The princess returned to Kraków together with some miners who accompanied her at her father’s order. Having set up a mine there, they soon reached salt deposits. And in the first block of salt they extracted, they found the ring Kunegunda had dropped in the Maramureș mine.”

It makes one wonder whether anyone in Kraków knows the story claiming that the famous salt mine in Wieliczka was started by Transcarpathian miners. No wonder why, having read several Transcarpathian legends, any cultured person cannot help but believe the people of that region were present at most of the significant world events.

Salt Route

Today, salt can be bought even at the smallest corner shop, and at the supermarket we can choose from several varieties – local, Himalayan, sea, rock, seasoned, and iodised. It is cheap and not considered particularly precious.

In the past, however, it was a strategic commodity – the lives of people and livestock depended on it. Salt allowed humans to develop the first way of preserving food that we still use to this day. It was a substitute for money – salt was, after all, the currency of the early medieval times. It was no coincidence that the meaning of salt is reflected in so many languages. Salt is called “white gold”, and the Bible refers to the best of people as “the salt of the earth”.

To understand how important salt was for the Transcarpathian region, all it takes is one look at its current coat of arms. It features a bear that symbolises the wild, forest-covered, impenetrable land it guards. There were never any big cities here, no industry, no advanced infrastructure. Even now, there is no motorway, and no Intercity train stops here. No wonder why – it’s hardly possible to gain much speed on the serpentine Carpathian roads.

Those areas were so remote and poor they were never fought for in any serious wars. This is why the salt deposits in Solotvyno affected not only the town itself, but the entire region: salt had to be extracted, transported, sold, taxed, and tolled. Therefore, a whole system grew around the salt mines, with its lawyers, medieval businesses, and a net of settlements.

Due to the mountainous terrain and mistrust for the local roads, extracted salt was floated down the Tisa river on boats and rafts, into the Kingdom of Hungary. The route had to be controlled and protected, while the salt needed to be taxed and stored in special hubs, from which it was later transported to the regions along the shores of the Tisa and Borzhava. For this reason, a whole network of various buildings was created: it includes castles and salt storages with trading rooms and offices of żupniks – managers who overlooked salt mining in the area. One of the oldest of such buildings is in Vylok village by the Tisa, on the present-day Ukrainian-Hungarian border. The building, constructed in 1417, still stands there today.

Modern researchers from the Uzhhorod National University, who spent years exploring this topic – historians Maria Zhylenko, Volodimir Moizhes, and Igor Prokhnenko – dubbed this network of roads and logistic buildings the “Salt Route”. It is, to some extent, a mental construct, since nobody used this name back in medieval times. Still, the name is accurate – it highlights the development of a ramified infrastructure around the salt deposits, and for centuries, this architecture was the main factor that contributed to the region’s development. The proof of this can also be found in the coat of arms of Máramaros County that formerly belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary and included the village of Solotvyno. Its coat of arms presents two miners with pickaxes in their hands. Nothing more important than salt extraction ever happened on this land.

Invisible castles

When drifting down the Tisa’s waters, one could go by without noticing the castles perched on its high shores – in Vyshkovo, Khust, Korolevo, and Vynohradiv. They are easy to miss – their ruins, stone skeletons of former power and strength, are now almost invisible, lost in thick shrubs. Those castles made for important defensive architecture by the “Salt Route”. It’s hard to tell whether they were built solely for the protection of salt transportation and trade, but it can be said with certainty that if not for salt rafting on the Tisa, there would be no need for them in the river’s upper course. Salt transports were the main reasons why local liege lords built those strongholds between the 13th and 15th centuries.

The castles, however, began to deteriorate quickly. First of all, they were all within the borders of just one state (initially, the Kingdom of Hungary, and then, Habsburg Monarchy). Therefore, they lost their strategic defensive purpose and served only as strongholds for the local nobility, and later – as garrison headquarters. During the Austrian times, the army was taken out of the forts, and the locals were allowed to take the castles apart for building material – in Vienna, it was feared that they would be used by the Hungarian freedom fighters.

Left without care and protection for centuries, the formerly powerful structures now look pathetic. No larger construction was preserved, just bits and pieces of leftover foundations and stumps of stone walls, disappearing among burdocks and undergrowth. Shrubs are even more merciless than frost, water, and wind, stronger than the enemy’s armies – their roots find their way between stones, slowly crumbling whatever is still standing.

Those castles tend to double as dumpsters, since tourists – looking for adventures and beautiful landscapes – used to come there for picnics, leaving all kinds of rubbish behind. In five hundred years from now, archaeologists will find broken vodka and beer bottles, empty packets of crisps and used condoms rather than swords and amphorae. Let’s try to imagine such a peculiar exposition in some future museum. It would be an apt illustration of our post-communist times.

On the other hand, however, those strongholds are indisputable proof that once, this land was part of Europe. If we proposed a thesis that the line of castles demarcates the cultural borders of the Old Continent, there would be no doubt this area was its beating heart (castles everywhere!). Moreover, Solotvyno is only thirty kilometres away from Dilove, where one can find a plaque indicating the geographical centre of Europe. Therefore, it’s where Europe not only used to be but still is – albeit invisible, just like the skeletons of castles, strewn among the shrubbery and litter.

The smugglers’ revolution?

It is said that in reality, all wars and revolutions start not with politics, but with private interests, women, and personal grudges. But when it comes to Transcarpathia, everything starts with salt.

The revolution against the Habsburg rule in Hungary, better known as Rákóczi’s War of Independence (1703–1711), also has its “salty” chapter. It features Tamás Esze, a small merchant who made a living from salt rafting down the Tisa river and then transporting it to Debrecen in central Hungary. In 1701, Hungarian salt managers from the aforementioned salt storage in Vylok stopped Esze and confiscated his goods, implying the merchant was selling his salt illegally. Simply speaking, they accused Tamás Esze of unlawful purchase of a state monopoly product, tax avoidance, and contraband. The whole freight – worth a fortune and including beasts of burden, used for carrying salt on land – was confiscated and left in Vylok.

Tamás Esze insisted the accusations were nothing more than slander and that he did all his business lawfully, but he never got his merchandise back. We’ll never find out the truth – whether Esze was a smuggler or just a victim to some local officers who wanted to fleece a shady merchant – but one thing is certain: Esze’s salt came at a great cost, and the price was paid not only by them but by the entire Habsburg Monarchy.

In the following year, Tamás Esze called together a unit of his friends and other people wronged by the local government. Together, they raided the salt storage, robbing it of money. Obviously, after the thievery, there was no going back to ordinary life, so the unit began hiding in the woods. Soon, the group joined Rákóczi’s army and fought against Austria until the end of the war. Tamás Esze turned out to be such a fervent fighter that in 1708, Francis Rákóczi raised him to nobility. It’s worth mentioning that nowadays almost nobody remembers the origins of Tamás Esze’s heroic story; the history elevated the resentful smuggler to a freedom fighter. One must admit it does sound like a very typical Central European narrative.

War in Donbas and Transcarpathian salt

Solotvyno is just as far from the occupied Donbas as it is from Amsterdam, but even such distance didn’t stop Transcarpathian salt from affecting the people in the war-torn region. Or rather not affecting, as the inhabitants of the mining cities of Donbas refused to move to the mining town in Transcarpathia.

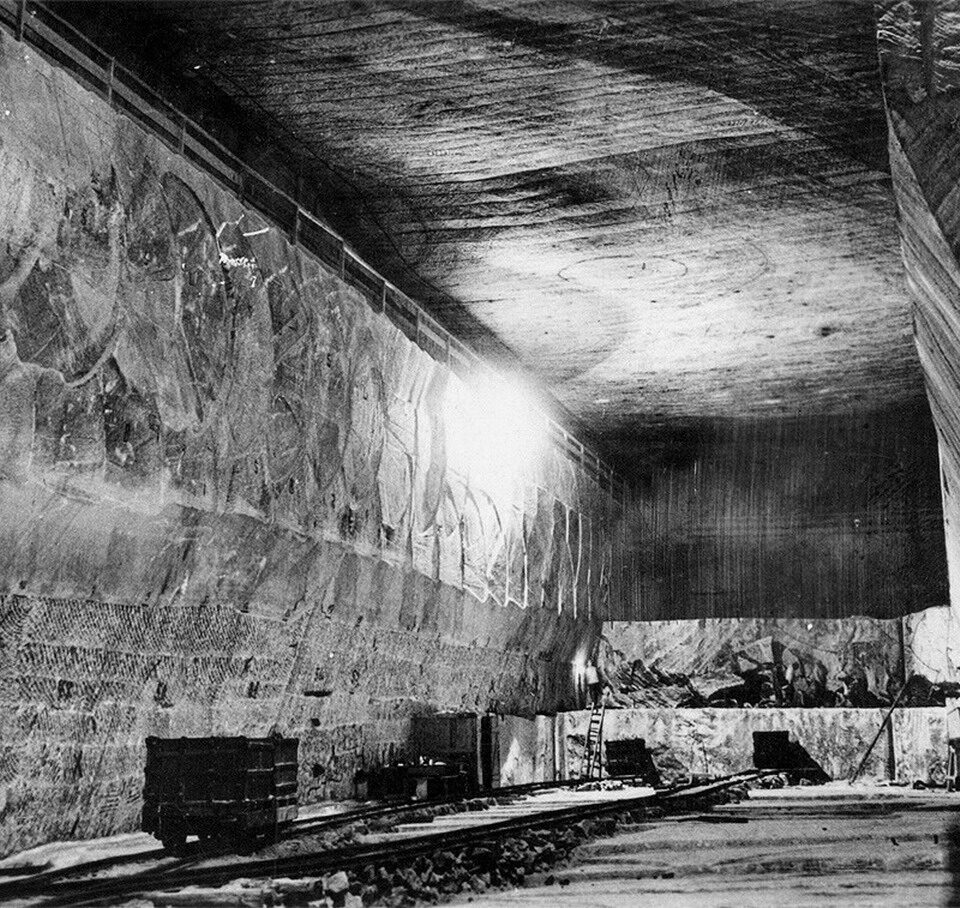

It all started two decades ago when old salt mines in Solotvyno were flooded – partly due to negligence, and partly because of natural disasters; after all, the river Tisa runs just several hundred metres away. One way or another, water began flooding salt-walled pits. Not surprisingly, salt began dissolving, and mines – made of the artificial solution caves – started to collapse. In 2010, the sinkholes were so large they became a threat to the entire town, and Solotvyno was deemed a site of the environmental disaster at a national level.

Authorities decided to resettle the inhabitants of the dangerous area and built a whole new town elsewhere: eight blocks of flats, seventeen houses, a school for three hundred students, and a kindergarten for a hundred and fifty. It was the first such town in Ukraine since 1986 when the city of Slavutych was built from scratch after the Chernobyl disaster.

The new settlement for the people of Solotvyno appeared quickly, but nobody wanted to move there. People did not believe earth could swallow their town overnight, and they had no intention of leaving their homes. In 2014, after the war with Russia began, the Ukrainian government decided to offer the uninhabited houses to Donbas refugees, but only three families agreed to go – nobody else wanted to move to a mountain town on the other side of the country.

The buildings stood empty until March 2021 when the fire erupted. The official cause was a grass fire that spread to buildings, but some say it was arson, meant to cover up widespread larceny that had taken place during construction. The fire was put out, but the ghostly settlement is now even less likely to welcome any new inhabitants.

So if you were driving by the Tisa river in March 2021 and saw a great fire, you probably wouldn’t have thought it was salt that started it. Invisible, lying in the ground and dissolving in water, it is salt that has been deciding on the region’s life for centuries.

Translated from the Polish by Aga Zano

Copyright © Herito 2020