Symbols and Clichés

The Mythological Foundations of History

Publication: 13 August 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESThe most basic concept of tribal identity was not erased with the advent of intelligent machines, because it is not reason but still emotions and the collective instinct that continue to drive the ambitions and even actions of large social groups and whole nations. In this respect, little has changed since the times we joined forces on expeditions against nations no longer extant, such as the Prussians or the Yotvingians.

In 2009 the small Bavarian village of Landshut staged its cyclical Landshuter Hochzeit, a re-enactment of the historic wedding that took place there in 1475 to celebrate the marriage of Hedwig of Poland (Jadwiga Jagiellonka) to Duke George the Rich (Georg der Reiche). The concept of “repeating history” by staging re-enactments with public participation is nothing new either in Bavaria or in Poland, or anywhere else in the world. In the context of folk or religious ritual, the “casting of the wreaths,” nativity plays, blow-by-blow reproductions of the stations of “Our Lord’s Passion,” and the concomitant processions were responses to what Roger Caillois some fifty years ago described as the primeval need to “enact the myth.” The various insurrectionist “skirmishes,” knightly “tournaments” and historic “battles” currently popular in Poland testify to a similar need, though it is unlikely that either the organisers or the participants of these “tableaux vivants” are aware of a fact that is obvious to sociologists and anthropologists: that what they are performing is a “metaphysical shift”; they are extracting isolated facts from the historical order and placing them in a symbolic order. In other words, they are contributing to the process of the mythologisation of history.

The year 2010 sees the anniversaries of two historical events: the sexcentenary of the Battle of Grunwald (Tannenberg) and the quatercentenary of the Battle of Kłuszyn. The date of the former, familiar to every Polish child, marks the victory over the Teutonic knights. The latter, known only to historians, was a victory against Moscow (and the Swedes). In the former we had several allies and a numerical advantage; in the latter the enemy had the allies and the greater numbers. We re-enact both, but only the former is publicised and broadcast nationwide. This is not only because Kłuszyn lies far beyond Poland’s present-day borders, but also because it has not been imprinted on our collective memory as indelibly and fundamentally as Grunwald. No-one seems to be irritated by the fact that, unlike the Slavic – and hence familiar-sounding – name “Kłuszyn,” the name “Grunwald” is foreign, German. Nobody is interested in the historical events that preceded the raising of the dust of battle; less still are they interested in the consequences of the victories. What is more, re-enactments of the Battle of Grunwald are designed not to recreate what actually happened, but to rekindle the vision created by Matejko, the atmosphere described by Sienkiewicz, and the film narrative compiled by Aleksander Ford. These three works not only blur into a single, very carefully intentioned image of the events of six centuries ago, but also build a mythologised historical perspective from which we continue to view our whole Polish-German relationship as neighbours, and at the same time our own history.

From this perspective, we lose sight of the obvious fact that the history of every country and nation, including the histories of both our own countries, are not purely testimonies to integrity, heroism and glory. On the contrary, they abound in instances of deceit, underhandedness and betrayal. Across history, the particularistic interests of the ruler and his or her supporters have too often been identified with the interests of the nation, and more frequently still the interests of one nation have disregarded injustice toward another. What for one country has been a victory, has for another been a defeat. Differences in historical perspective implicate diametrically different emotional reactions to the same facts. Democracy, political correctness, global thinking and the interests of minority groups are not concepts that are very strongly rooted in the contemporary world. They were not obvious values in the past, or even values at all. Today’s euphemistic political language has to illustrate concepts that are still carving out places for themselves in developed societies, while at the same time we are witnesses to processes that run counter to our contemporary humanitarian vision of the world. Religious and race wars rage before our eyes in many countries of the world, even on the fringes of Europe. The most basic concept of tribal identity was not erased with the advent of intelligent machines, because it is not reason but still emotions and the collective instinct that continue to drive the ambitions and even actions of large social groups and whole nations. In these circumstances, reason will more likely suggest effective ways of channelling tribal aggression and optimum leveraging of human potential to achieve vague but skilfully mythologised aims. In this respect, little has changed since the times we joined forces on expeditions against nations no longer extant, such as the Prussians or the Yotvingians. In this context it is easy to forget that the history of our coexistence as neighbours, and hence the entire history of Polish-German relations, cannot be examined today solely from the perspective of the interests and arguments of the rulers of the past. And yet, our judgement of the historical facts has not yet been subjected to revisions and adjustments that would render it adequate to today’s values as generated by the European Community model of amicable co-existence.

The Polish cognitive (and interpretative) perspective was constructed in the context of Prussian participation in the partitions of Poland towards the end of the 18th century, whose final act, we should add, was played out almost before the ink had dried on the 3rd May Constitution enacted by the Polish Sejm, the first constitution by an enlightened state in Europe, and only the second in the world (after the constitution of the United States of America). It were the partitions that caused the Polish army to come out on the side of Napoleon Bonaparte, and against the rest of Europe, and to accompany the French emperor all the way along his route of military encounters, right up to his final defeat, which also proved to be a defeat of Poland’s dreams of the revival of their state. This defeat was articulated emphatically in the terms of the Congress of Vienna (1815),which, from another perspective, was considered one of the crowning moments in the process of uniting Germany under Prussian rule, and from that point on the thought of freedom became the primary goal in Polish society. Since the Romantic period, it was also the main thematic axis of artworks, the vast majority of which were focused on issues connected with the struggle for national liberty. This produced, as one of its foremost models, the figure of the hero who put his life on the altar of the Fatherland. Suffice it to say that the Polish national anthem was born as The Dąbrowski Mazurka in 1797, when the Polish Legions were forming in Italy and preparing to set off in support of Napoleon and to wrest their country from the hands of the partitioning forces.

This new perspective has also brought with it a sudden and violent revaluation of the way cultural identity was understood. Polish culture had since the earliest times been pluralist, absorbing styles and works created even in quite distant regions – Russian, Hungarian or Turkish things were no less attractive than French, German, Bohemian, Italian and Flemish imports. First master craftsmen and later artists from across Europe found out that Poland offered no less ideal conditions for their work than those discovered by Polish émigrés abroad; some continued to work here all their, much lauded, lives. Even towards the end of the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski[1], the painters most sought after by the aristocracy were Italians, who made portraits of statesmen and the king himself. This supranational conception of art was in no way at odds with the deeply rooted sense of a Polish national identity at the time when Poland was in possession of its statehood. It was only its loss that awakened the society to the issues of our diversity, and sparked the need to pluck the Polish element out from the multitude of threads interwoven in the cultural tapestry across the broad swathe of Europe that was the first Polish Republic. Eventually, over the course of the 19th century, the syndrome of loss of roots dictated Poland’s vision of history, which became more strongly accented as increasing numbers of Polish artists diluted their pedigree or abandoned their native language.

From this traumatic perspective Germany was not viewed in Poland as a federation of sovereign countries, but as a Prussian hegemony with a programme to pursue Chancellor Bismarck’s policy of Germanisation in respect of the Polish nation. Naturally, this policy met with a hostile reaction from the subordinated society. This enmity, in turn, was ably fuelled by the propaganda and secret services of another of the partitioning powers: the Russian Empire. In the second half of the 19th century, following the failure of two successive Polish national revolts (in 1830 and 1863), the positivist current of organic work battled for primacy in Poland, with the construction of a national historiosophy and the dissemination of a mythologised version of history based on legends such as that about the Krakow princess Wanda who “wouldn’t have a German.” Art and literature, from Adam Mickiewicz to Stanisław Wyspiański, became a fertile ground for fostering similar legends; in other words, throughout almost the entire 19th century. It was at this time that a resident of Greater Poland, Michał Drzymała, became a national hero when, refused permission by the Prussian administration to build a house, he and his family set up home in a travelling wagon. It was also at this time that one of the foremost proponents of Polish positivism, the poetess Maria Konopnicka, wrote the words of the anthem Rota, which is still sung today, featuring the words: “The German shall not spit in our face or Germanise our children.” This came about after a Prussian expropriation campaign and a rebellion among the children of Września, who disobeyed an order to say their prayers in German. Even more interestingly, the music to Konopnicka’s poem was written by a resident of the Germanised Warmia[2] region, Feliks Maria Nowowiejski, to mark the jubilant celebrations of the quincentenary of the Battle of Grunwald. The ceremony was held on what is now Matejko Square in Krakow, by the then newly erected Grunwald monument.

The work of other Polish writers, among them the Nobel laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz, was also dedicated to “uplifting hearts,” with descriptions of the glory of the Polish troops. In the field of painting the eulogist of this glory and the illustrator of history was Jan Matejko, also a paragon of subordination to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and a student of the Munich Academy. Like many other graduates of the Munich school, Matejko saw no contradiction between the content of his works and the fact that they were exhibited in the capitals of the states that ruled Poland. On the contrary, he prided himself on his triumphs at exhibitions in Vienna and Berlin. Another Munich alumnus, Wojciech Kossak, even earned the title of court painter to Emperor Wilhelm II. Among the writers who worked and were active in Germany were Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, the author of fictionalised history of Poland that ran into scores of novels, written with the express purpose of sustaining the national identity, and Konopnicka herself, an advocate of active resistance against Prussia.

Similarly, there were numerous entrepreneurs, including some from among the aristocracy, for whom their patriotic ideals presented no object to forming lucrative companies with the participation of foreign capital. In Greater Poland and Silesia, the most highly industrialised regions, this was primarily German capital; east of the Vistula it was Russian capital; and in the south Austrian capital, though not in hard cash but in the form of assignations of land. This was the “Joseph’s colonisation,” designed to “civilise” rural areas by settling Germans there. Even today, traces of the differences in economic policy in the various partitions are still visible in Poland, and the impression of heterogeneity is reinforced by the varying degrees of urbanisation of towns, but also by accents, vocabulary and customs, including culinary matters. We should add, however, that what the partitioning powers had to offer ranged from a deprivation of national identity with prosperity (Prussia) to a deprivation of national identity without prosperity (Russia), while the Poles’ dream was a sovereign state able to realise its own economic potential. This is the vision underpinned in the book of another Polish Nobel Prize winner, Władysław Reymont, The Promised Land, which examines a model, which proved to be utopian, of a combination of Polish, German and Jewish capital to reinforce and modernise the industrialisation of Łódź, a city largely shaped by German settlers. The message of this book was not picked up until Andrzej Wajda made his condensed film image showing the true face of this city on the threshold of the 20th century.

A hundred years of partition did not uproot the egalitarian need of the Poles to strike out for freedom. This became abundantly clear not only in the formation of the Polish Legions, which, it should be remembered, fought on the German side in World War I, but also during the postwar plebiscites and uprisings in Silesia and Greater Poland. Given this slant on things, should someone have remembered the instinctive German reaction of solidarity towards the November uprising (1830), or the fact that our national bard[3] was afforded the conditions he needed to write his Forefathers’ Eve, which became known as his “Dresden” work from the place where it was written? Was there time for the nation to liberate itself from its trauma, its syndrome of injustice and heroic sacrifice during the two brief decades between the two world wars? Was the period of rebuilding the new state conducive to calling Poland’s rulers to account for their errors and analysing the combination of circumstances that pushed Poland into the arms of the partitioning powers? Who, in a besieged fortress, would have sown the seeds of defeatism and attempted to debunk the myths of the honour of the free nobleman who was above usury, commerce and industry but whose one word could halt the proceedings of the Sejm, and stood in the way of the royal absolutism that reigned in the neighbouring powers because he himself had elected the king and bound his hands with “pacts” guaranteeing the inviolability of long-held privileges? Was it permissible to make diagnoses questioning the power status of a state entity run by powerless kings, often representing foreign dynasties and their political interests – kings who traded in royal assets and who spirited all their own wealth out of Poland because it was not the property of the Polish Crown? And was it right to speak out about the ambiguous role of the Polish magnate estate, which prioritised personal or dynastic benefits above the Polish raison d’état?

But there is another side to this coin. From as early as the beginning of the 16th century, Poland had been the most democratic country in Europe of its day. Ten percent of society had either active or passive suffrage, several times more than in other countries, and the egalitarian structure of the Sejm itself assured “crested” society broad access to legislative procedures. This enabled the nobility to lobby for and obtain the right to freedom of conscience and confession, something that was subject to bloody and merciless punishment elsewhere – to mention only the French persecution of the Huguenots or the English of the Catholics. It was this tolerance that allowed the Poles to avoid religious wars, to even avoid becoming embroiled in the exhausting Thirty Years’ War, and enabled them to preserve the unity of their vast country with its widely varying cultural and confessional traditions. It is important to remember what a strong divisive factor the choice of confession was in Germany, and how long it hindered the uniting of the country. The Poles, by contrast, were able to generate a new liturgical formula that fused Catholicism and Orthodoxy in a single Uniate Church, which was in a sense a manoeuvre to satisfy the residents of the Commonwealth’s eastern regions, and hence ensured relative peace across this territory. And it was this tolerance that allowed the country to take in thousands of fugitives from less tolerant countries in Europe, and so further enriched Polish culture with new elements. But, perhaps it was precisely this tradition and this concept of freedom that drove Poland apart when it came to fighting the progressive disintegration of the Commonwealth over more than two decades at the end of the 18th century? During this period it was the attachment to personal property that took precedence,in particular when that property was the source of vast fortunes, most frequently in the form of the enormous farmed estates in the east.

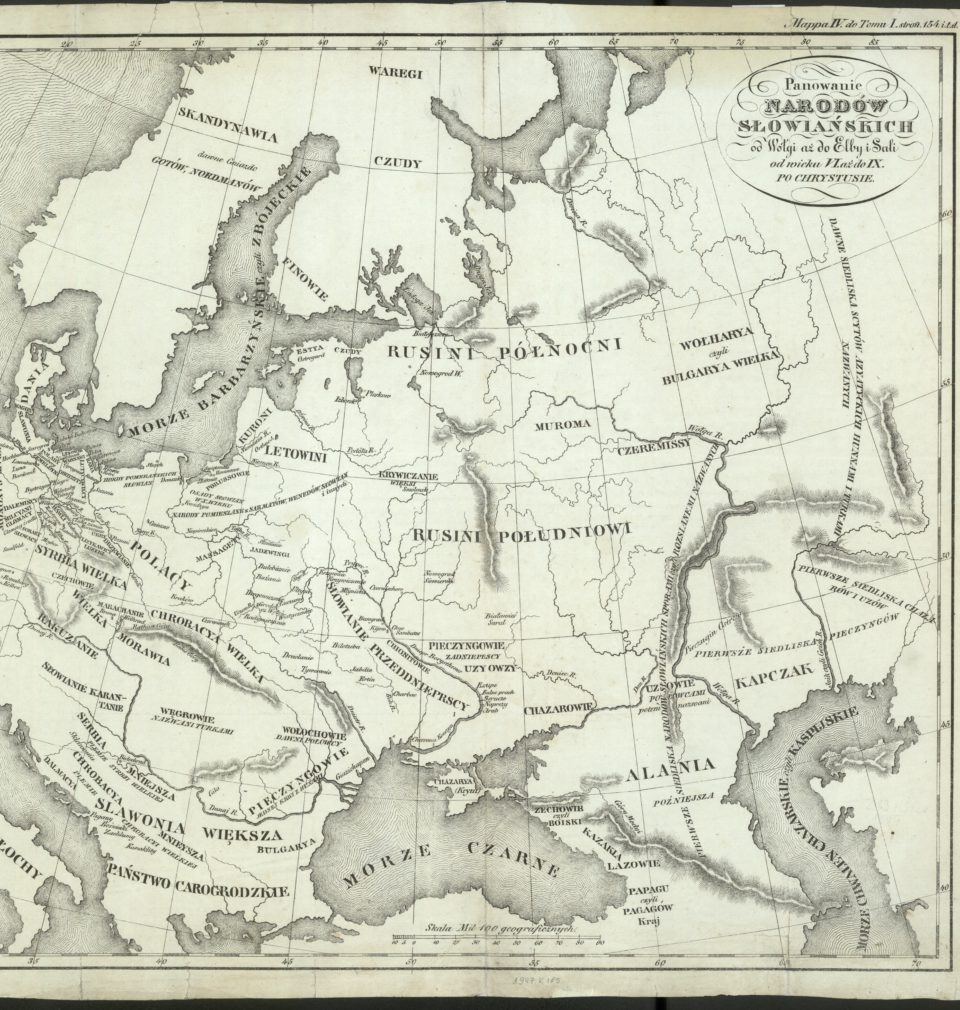

The German concept of the “Drang nach Osten” carries pejorative connotations in Poland, and so no-one was ever bold enough to speak out openly about Polish expansionism in the same direction, begun by Bolesław I the Brave, re-started by Casimir III the Great in the 14th century, and pursued resolutely by the Jagiellons. This latter dynasty, dominated by the Lithuanian aristocracy, saw little potential in the progressively Germanised Silesia, or in Pomerania and Eastern Prussia. The their ambitions concerned not the crowded towns and closely spaced fortresses of the western and northern lands, but the expansive meadows of White, Red and Black Ruthenia; not the valleys of the Oder and Vistula but the Black Sea steppes; not the Baltic but the Black Sea itself. Was this not the reason for Władysław Jagiełło’s tardiness in taking advantage of the victory at Grunwald? Was this not why Sigismund I the Old accepted the Prussian fealty and bestowed those lands on the Hohenzollerns as a hereditary privilege instead of conquering them and taking direct possession of them himself? After all, those were his rights accruing from the war. But the Polish economic power that emerged rapidly across the great eastern estates was based on revenue from agriculture, and from wars and tributes obtained from the Tatars, the Turks and the cities of Ruthenia before they were subordinated by the Russian tsar.

Administration of the land, politicking and warring were the essence of the szlachta’s freedoms. The towns and their occupations – crafts, trade, manufacture, banking, and also art and learning – were left to foreigners, infidels and the people of lower states. It was they who worked, traded and produced goods, but as a class they did not benefit from any grand privileges or political influences. They were necessary, and so they were tolerated in all their diversity to an extent not found in neighbouring countries. Polish towns accepted Jews, Germans, Flemings, Scots and Netherlanders, Ruthenians, Tatars and Armenians; Protestants, Calvinists, Orthodox and Muslims. We were a country open to other people, but not to other economic models. When intensive change processes began to take place in Western Europe as a result of industrial progress, the old socio-economic structure ceased to guarantee prosperity and security in Poland. This was why, unlike Germany, Poland was unable to pick itself up after the wars with Sweden in the mid-17th century. The cities, towns, palaces, courts and castles pillaged by Charles Gustav could not get themselves back on their feet without the drive that countries in the throes of the industrial revolution gained from the change in the economic system. Gradually, too, Poland’s moral alibi as the “bastion of Christianity” defending Europe from the Turkish horde was waning, even though it really had played this role for several centuries, worth to mention its role in the victorious battle against the Turks at Vienna in 1683, which decided the outcome of the war.

Circumstances that were not conducive to historical analyses or a revision of the approach to past ages persisted in Poland throughout much of the 20th century. Not even Germany’s role in the restoration of Poland’s sovereignty after World War I has been properly examined from every angle, because we received it as a package with the Russian October Revolution, which robbed thousands of families in the Eastern Borderlands of their homes and property, not to mention the cost in lives. The Nazi aggression in September 1939, with the insidious support of the USSR as provided by the secret Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, and the unprecedented terror of the occupation period did not end in true victory for Poland. Aside from the traumatic memory of the last war, which is still raw, a significant fact in the consideration of Poles’ attitudes towards their own history is that the Yalta conference delivered the country into bondage once again, drawing it into the sphere of Kremlin policy and so confirming the theory, broadly held in Polish society, of the existence of two enemies. Throughout the cold war Poland was subordinated to the political line dictated by Moscow to the whole “socialist bloc.” This dictated as the correct and sole available response resounding acceptance of the division of Germany into occupation zones, of which only the GDR could be counted among our country’s “friends.” History teaching and interpretation was conducted in a similarly politicised vein, which for decades facilitated the defence of the Oder-Neisse border. The argument that the “Western and Northern Lands” belonged to Poland was justified in terms of their “return to the matrix,” with a transparent reference to Poland under the Piasts. No mention was made of the repeated political neglect that led to the Silesian Piast dynasty being deprived of its national identity, and an even deeper silence shrouded the fact of trade in entire regions by successive rulers from the 13th-century Bolesław II the Bald onwards. No explanation was offered as to why Duke Konrad of Masovia had the Order of the Teutonic Knights of St Mary’s Hospital in Jerusalem – popularly known as the Teutonic knights – brought to Poland, because the concept of a crusade against the pagans of the North did not fit with the secular world view of the ideologists in the People’s Republic of Poland. Instead, extensive exposure was given to the sinister legend surrounding the Order, despite the fact that this was incompatible with the high praise of the castle erected in Malbork by the Order, deemed a masterpiece of defensive architecture and still admired by large numbers of tourists today. What was more important, was to distract society’s attention from the westward shift of Poland’s border with the USSR. Silesia, the Lubus Land, Pomerania, Warmia and Masuria were populated with people resettled by the USSR from the Eastern Borderlands, and Lemkos, an ethnic group from the Bieszczady region not fully aligned with the Polish identity, were sent to the Coast. Taken to their new destinations on repatriation trains, the resettled people from the east did not feel at home in these new lands, and so did not take care of the flats, houses and farm buildings “given” them, which had so recently been tended to maximum productivity with the forced labour of nations subjugated by Hitler, above all Poles. These newly resettled Poles, like the previous inhabitants of the Western Lands annexed to Poland, and like all displaced persons always and everywhere, waited for a chance to return home, but that chance did not come, and could not come without a radical change to the laboriously created post-war status quo.

The official policy in respect of Germany was not altered by the letter from the Polish bishops to the German bishops that spoke of mutual forgiveness. Not even Willy Brandt’s visit to Poland brought significant change, though it did bring the signing of the pact recognising Poland’s western borders. Meanwhile, two new generations were born and grew up in the Reclaimed Territories generations which do not yearn to go back to a paradise lost east of the river Bug, nowadays in Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus. They are attached to the places where they live, and are restoring their tangled histories to them, learning the German names of the places and people with which the local castles, palaces and estates were once connected. They are aided by the gradual revision of history that has only begun in Poland after 1989, though the results of this research are still only local, and are limited to the histories of individual towns, cities, estates and castles. Broader studies are conducted by both Polish and German research teams (often in amicable cooperation), but their results have not yet been fed into mainstream teaching.

The process of passing over history in silence occurs, also, on the other bank of the Oder, where the pre-1939 historical option is still eagerly accepted, but the true magnitude of the Nazis’ war crimes are not the subject of general education of German society. Hence the popularity of the attitudes represented by Erika Steinbach, to which the Polish society, which was enthusiastic regarding German reunification, reacts very badly. It is now becoming clear that difficult, painful issues connected with the last war have not been sufficiently analysed for them to be closed. Perhaps this is the task for the next generation of Poles and Germans to face. We should be confident that both sides will have enough good will to ultimately draw a line under the balance sheet of injury and loss. Before this may happen, however, we need to work towards the objective of illuminating all the leads to what is still the concealed core of truth.

There is nothing that suggests that the outcomes of desk research will have any influence on society’s view of history, at least as long as fictional battles always ending in a victory for the House of Jagiellon are played out on the fields of Grunwald, once soaked with the blood of real people. After all, before much time had elapsed, Casimir IV Jagiellon married Elizabeth, so joining the Jagiellons with the Habsburgs, and the same dynasty later produced not only the Jadwiga who was then married off to a Bavarian, but also her numerous sisters. One of them, Zofia, was subsequently the mother of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Albert Hohenzollern; another oned, Anna, married Bogusław X, Duke of Pomerania; third of them, Barbara, married the Saxon duke George the Bearded, and the youngest, Elżbieta, wed the duke of Legnica, Frederick II. Suitably sumptuous weddings were held in Królewiec (now Kaliningrad), Szczecin, Dresden and Wrocław, and these are also worthy of recollection if we are to build peace in Europe.

***

[1] The last Polish king, forced to abdicate by the partitioning powers.

[2] In German called Ermland.

[3] Adam Mickiewicz

Copyright © Herito 2020