Kharkiv

Art is important regardless of war

Publication: 8 May 2023

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESCulture and art produce new meanings and messages, help society analyse and interpret the events around it, and think about the future. If we forget to train these skills during the war, then after the victory we will not remember what we actually fought for.

Wartime Kharkiv likes to call itself “a reinforced concrete city”. Metaphorically it refers to its indomitable inhabitants and literally to the architecture that helped them survive the worst days of the war. One of the buildings that have been transformed into shelters is the YermilovCentre – a centre for contemporary art named after Vasyl Yermilov, one of the most important creators of the Ukrainian avant-garde. At the headquarters of this institution – the ferro-concrete basement of Kharkiv’s Vasyl Karazin National University – I meet its director, Natalia Ivanova.

Kaja Puto: This is a perfect place for a shelter. Did you suspect before 24 February that the YermilovCentre might suffer such a fate?

Natalia Ivanova: For the residents of eastern Ukraine, the war had begun in 2014. For the first eight years, Kharkiv wasn’t its arena, but lived in its shadow. Artists sometimes joked, “Natasha, if things go wrong, we’re coming to your place”. However, such an escalation was not expected. I never imagined that I would come to live here. Even when something was already hanging in the air.

K.P.: As recently as 22 February, you opened Oleg Kalashnik’s exhibition…

N.I.: Oleh had called me some time earlier and said: “I came up with a project for my forty-fifth birthday. It’s about the toy soldiers I used to play with as a child. There were no other toys in the 1980s, so I used to build them houses from pieces of brick. I would like to go back to that. Make sculptures, installations, experiment a bit.” We gave him access to our main space, although we don’t usually do this for one-man shows.

K.P.: The exhibition was titled “Enfant terrible”.

N.I.: One of the works on display depicted black toy soldiers on a red background. Its title is “Game over?”, with a question mark. When we were assembling it, we talked about this title, we said that the question could be interpreted in two ways: to what extent children’s game of war is childish, or whether adults actually want to play at it too. Someone laughed at that and told us to stop provoking fate. And a colleague answered him: “After all, Kalashnik is such an enfant terrible.” So we already had the title, then we opened the exhibition, and two days later we saw a war live. Explosions, bombs, planes.

K.P.: What were the first days of the YermilovCentre as a bunker like?

N.I.: Friends of artists and students came down to see us. We called all our friends, but at first not everyone wanted to leave their home. It was hard to believe that all this was really happening. Pavlo Makov, who represented Ukraine at the 2022 Venice Biennale, only came to us with his family when a missile hit the street below his window. And then from here he would give interviews to foreign journalists for days.

We had some bricks, boards and tires in the basement, and made beds and mattresses out of them. Whoever could manage brought warm clothes with them. No stores or ATMs worked, the city of one and a half million people was completely empty, if you exclude the petrol queues. In the university’s cafeteria, volunteers cooked the food we ate, with products we delivered from a café whose owners we knew. They did not want them to go to waste.

The newly opened exhibition saved us, because there was something to occupy the children with, which is not easy in a concrete-made space without windows. They played in the sandbox, where Oleh placed small candles in the shape of toy soldiers. And sculptor Vladyslav Yudin was making clay whistles shaped like cockerels – a traditional Ukrainian toy – with the kids. Adults also joined in.

K.P.: On 1 March, the Russians aimed a rocket at the Kharkiv Regional Council, on the other side of Freedom Square, just a few hundred metres from you.

N.I.: It was in the morning, that is, at the time of writing messages like: “How’s it going?” to friends on Telegram and Viber. We were sitting glued to our phones and suddenly there was a bang. I thought the door had exploded. Glass showered down from the windows of the huge university building above us. I went outside and saw flowers freeze in them. There were planes flying over the city, it was terrifying. I won’t say that you can get used to rocket attacks and bombing is an even higher-grade stuff.

K.P.: “How’s it going?” is also the title of an art project that you created in those days.

N.I.: The artists and photographers who lived here documented our everyday life. They took pictures of all those strange contraptions we used for sleeping, cooking, and washing. They accompanied us when we spent hours discussing the war, art, and Ukraine. We published this project on our website.

K.P.: How long did you live here?

N.I.: Eleven days. On 7 March, the lights went out, and it was very hard for us here, because we only have electric heating, and March in Kharkiv is still deep winter. We couldn’t find an electrician to fix the breakdown. People moved around Ukraine, some went abroad, others returned home.

K.P.: And you?

N.I.: I went to Kuzemyn, it’s a village in the Sumy region. It was much more peaceful there at the time. We have a house there, where we had organised art residencies back in 2021. I also invited the artist Konstyantyn Zorkin and his whole family there.

By mid-March, the Russians had managed to destroy nine hundred residential buildings in Kharkiv. As I searched for an electrician all over the city, I saw this conflagration with my own eyes. We wanted to create some kind of response to this nightmare. Kostya didn’t have any materials or tools with him, but he found some boards, metal fragments and a file in the village, which he used to make himself a chisel. He made, for example, a city out of rusty metal or a landscape of a wartime village. We showed these works in autumn in our basement as an exhibition entitled “Protective Coating”.

K.P.: When did you return to Kharkiv?

N.I.: In May, when electricity was successfully restored in the YermilovCentre. The situation in the city was already somewhat calmer, the Russian troops had been pushed back. We returned to work then.

We made some of our space available for the Kharkiv Media Hub, a safe place for journalists. Military briefings, for example, are held here, and some foreign media representatives still hide here during air raid alarms, because they have it stipulated in their contracts that they have to go down to shelters. Kharkiv residents are unlikely to do that anymore.

K.P.: When the sirens go off, even university employees no longer come down here?

N.I.: Most go out into the corridor, which provides relative safety if a rocket hits nearby. The Russians are still firing at us, but only with rockets and drones – they are too far away from Kharkiv to use artillery or bombs. They mainly target critical infrastructure, such as power plants. To some extent, we are used to the sound of sirens. And I feel lucky, because I work in a shelter every day.

K.P.: And to go back to your activities…

N.I.: We applied for a grant to the Museum of Contemporary Art, which had received money from UNESCO. Thanks to it, we were able to organise more residencies in Kuzemyn. We invited Kharkiv artists to work on their projects there. We recorded many interviews with them, for example about why art is important during the war. The result of this work will be shown in an exhibition that we plan to open on the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

K.P.: So why is art important during war?

N.I.: Art is important regardless of war, but war increases its importance. Culture and art produce new meanings and messages, help society analyse and interpret the events around it, and think about the future. If we forget to train these skills during the war, then after the victory we will not remember what we actually fought for.

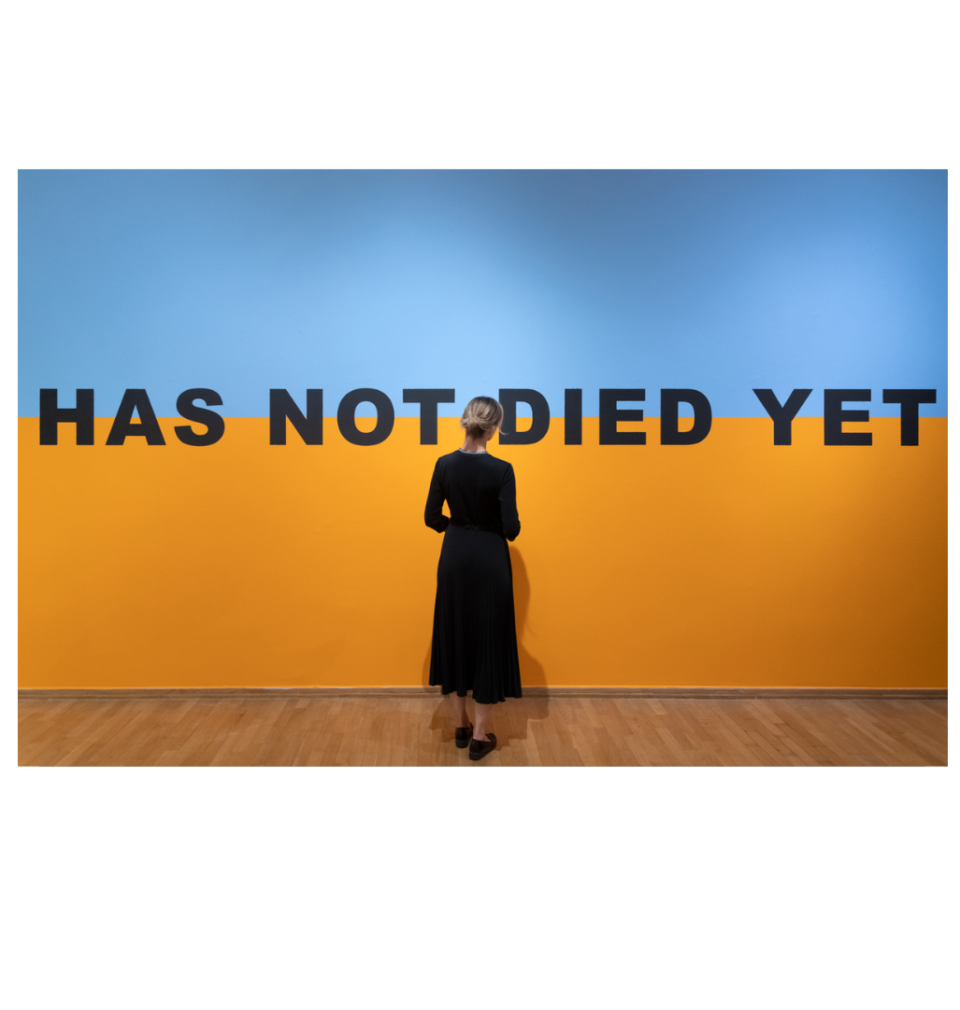

Art is also part of Ukrainian identity. By creating Ukrainian art, we counter Russian propaganda, which claims that Ukraine does not exist as a separate state and Ukrainians are not a nation.

K.P.: The YermilovCentre also hosts film screenings, literary meetings…

N.I.: Serhiy Zhadan even organised a music festival here called Music of Resistance. He played with his band Sobaky v Kosmosi (now known as Zhadan and the Dogs), invited Svyatoslav Vakarchuk from Okean Elzy and many great musicians from all over Ukraine. And the Kharkiv Literary Museum organised a Night of Museums with us, focused on the theme “Let’s Escape from Moscow, We Want Europe”.

K.P.: We are in the basement of the university now. The current building was put up in the 1930s in the Constructivist style. After World War II, it was rebuilt in the vein of Stalinist Empire style. This kind of architecture is a hallmark of Kharkiv. How do you escape Moscow – or, more precisely, Soviet heritage – under such conditions?

N.I.: I understand this legacy more as an architectural heritage that Russia is now trying to destroy. For example, it ruined the Palace of Railway Workers’ Culture, a wonderful example of local Constructivism. Personally, I am proud of our architecture, which in the 1930s was unique in the world.

I really like Kharkiv. Its vast spaces and air masses evoke a sense of infinite possibilities. This city is like a mechanism, like a machine in which everything turns like gears. This is also reflected in its monumental architecture.

K.P.: And what was in this basement before the YermilovCentre was built in 2012?

N.I.: In Soviet times there was a student canteen here, and the Bunker nightclub in the crazy 1990s. Its interior was all maroon, silver, and navy blue, the concrete columns were covered with carpeting. It had many levels, steps, and balconies. It operated for several years, and in the early 2000s they closed it down.

Those were strange years. Some Kharkiv residents were becoming millionaires, but lecturers were not paid salaries. We formed an association with a group of alumni. We wanted to do something for our university, and we needed a separate organisation for this, because without it the money raised for the uni vanished into thin air.

We bought computers, renovated lecture halls, and started publishing academic books and magazines. We had the money to do this, because some graduates succeeded as local businessmen. The rector suggested that we develop the space in the basement of the university. At the time I had no idea what I was talking about, but I proposed a centre for contemporary art.

K.P.: It took you five years to create it.

N.I.: This was before the era of social networks, there was no way to get information quickly. I read and I travelled to understand how contemporary art is exhibited and I learned that institutions like the one I intended to open play a broader role than ordinary galleries. As for modern cultural centres in Ukraine at the time, Lviv’s Dzyga existed, and the Arsenal of Art was already operating in Kyiv. And that was it. Anyway, there are still not enough of them today. Such places are missing especially in smaller towns.

Here, on the ground, I was helped tremendously by Tatiana Tumasyan from the Kharkiv City Gallery. And by the strength of our city, that is, the students, of whom there were four hundred thousand before the war, making up almost a third of the population. Many of them study creative majors: art, design, music, directing, architecture, media studies, cultural studies, and so on. Kharkiv is an industrial city, but it buzzes with artistic energy. The history of the Ukrainian avant-garde, headed by Vasyl Yermilov, and the biographies of various nonconformists are behind this buzz.

K.P.: The war is helping the world learn about Ukrainian art.

N.I.: I wouldn’t want it to be that way. I mean, of course, I’m glad that Ukrainian artists are now showing their work and thus promoting Ukrainian art in Europe. Yevhen Svitlychnyy went to Ireland and already has his second exhibition there, Oksana Solap is showing her works in Austria. But they all deserve to be known not only because there is a war going on in their country, especially since it will end someday.

On the other hand, the flourishing of Ukrainian art is partly due to the turbulent times we’ve been living in here since 2004, since the Orange Revolution. Society is bustling, activism is booming, new political movements, new identities are being born. Art likes such things.

Translated from the Polish by Tomasz Bieroń

Copyright © Herito 2020