The City and the Museum

Museum Grodno. The City as an Artefact

Publication: 17 August 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESAs a physical and imagined space Grodno provided modern Belarusian identification opportunities which were connected not only with its heritage, but also created a possibility of treating the Lithuanian, Polish and even Jewish history as part of their own city, as in a painstakingly deciphered palimpsest.

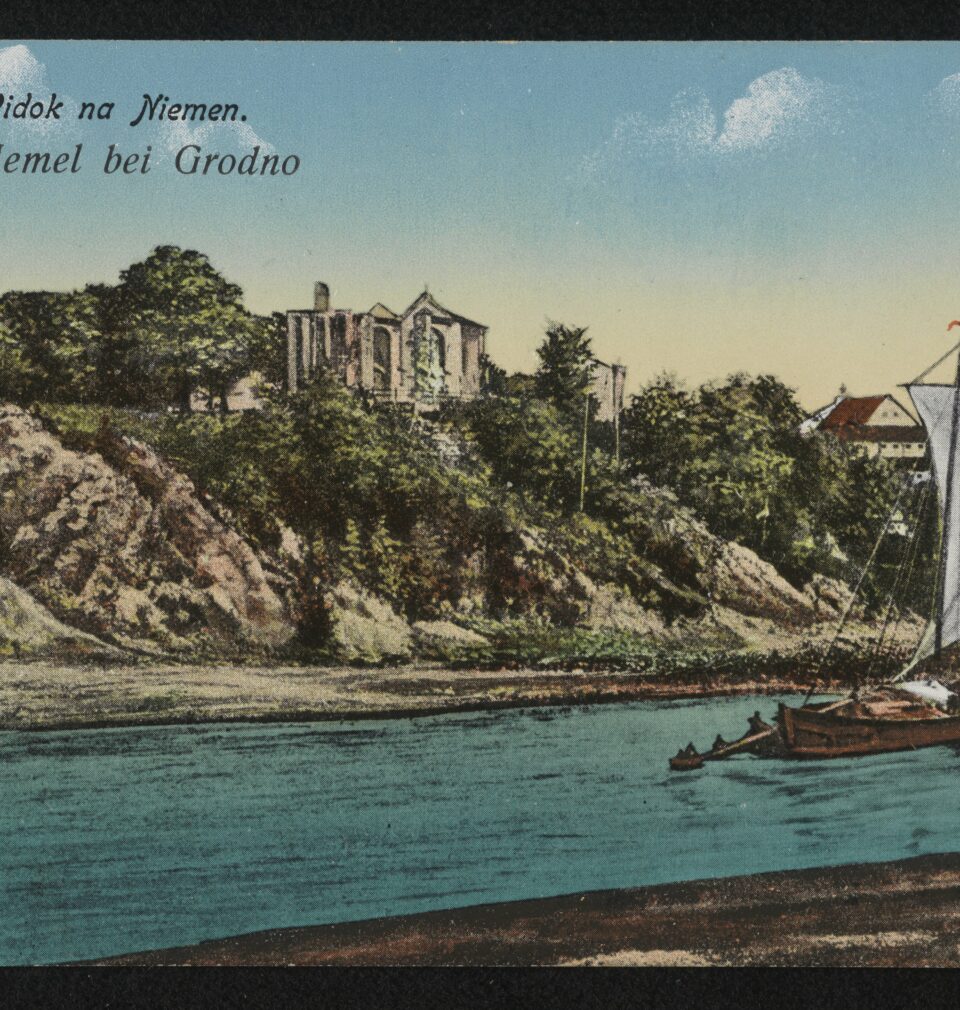

Soviet Grodno (Hrodna) was a new city – the majority of its former inhabitants had been murdered or expelled during World War II. Less than one third of the prewar population remained and the Soviet industrialisation turned it into a rapidly vanishing minority in this city on the Neman. After 1944 the permanent display in the city museum was so taciturn on the city’s past that the visitors – Soviet pupils and workers – started to complain: we want more history.

In the search effort of local actors the city space itself was increasingly taking over this function. Amateur historians had long been collecting everything which seemed old. And the dividing line between new and old was situated in 1944, while the magic border of the past, something yet more ancient, was put in 1939. The bygone times fascinated the collectors, who gradually became specialists in particular areas.

In 1983 Alexander Gostev published an article about coins from Grodno in Khimik, a magazine of the chemical works AZOT. In the example of seemingly innocuous findings he recalled some aspects of local history which had been heavily censored or ideologically distorted before. The author explained to the chemical workers how Lithuanian coins with Polish inscriptions and an image of a Saxon Elector had found their way to Grodno. He also mentioned in passing the history of the Northern Wars[1]. While doing that, he avoided ideologically hazardous areas. And thus, of his own accord, far away from professional Soviet historians, the University and the Academy of Sciences in Minsk, he started to rebuild the Belarusian history of the city (apart from a small publication on the history of architecture in Grodno, issued in 1960 in Moscow, there was only a tiny book on the history of the city by Kudriashov[2]. Only in 1989 a lexicon by Shamiakin appeared, with a more extensive historical outline[3]. Both these publications, as well as Gostev’s article, were in Russian.)

Gostev is an excellent example of how fascination with history and the place you live in may become a driving force of social activity and discovering your identity. This son of a Red Army officer, born in Kaliningrad and christened Alexander, did not feel attached to Grodno and the surrounding area. When he moved there, he developed an interest in the local tradition, first as a student and then as a physicist working in the R&D department of the AZOT works and in other Soviet institutions. An important role was played here by his wife Liuda, born in Grodno right after the war, in an Orthodox family whose members defined themselves as Belarusians. Gostev’s antiquarian preoccupations increasingly focused on all that could be regarded as old: medieval bricks with runic inscriptions, shards from demolished houses, tiles from stoves which no longer produced heat, glass vessels from no longer existing pharmacies, books, prints, postcards and newspapers. The crucial thing was for the object to look original and old. But this fascination produced something more than just a private cabinet of curiosities. In-depth studies on the history of the city resulted in a chronicle, which was published in 1993 under the title Kronon[4].

Gostev’s private interest in the local history also served the discovery of its manifold Belarusian aspects. In their collecting passion Alexander and his wife were exceptions, for very few such “insane people” could be found who would jokingly talk to all the amassed bricks, old papers and chips of china. As a physical and imagined space, Grodno provided modern Belarusian identification opportunities which were connected not only with its heritage, but also created a possibility of treating the Lithuanian, Polish and even Jewish history as part of their own city, as in a painstakingly deciphered palimpsest. Accidentally discovered relics of a seemingly alien history of the city were approached by Gostev and other enthusiasts like him not as isolated cases, but as integral parts of their surroundings, which had to be highlighted and safeguarded.

The fact that Gostev was not alone, and that the Grodno palimpsest was no longer perceived as a symbol, but as a tangible urban space, is attested by smaller or bigger initiatives of individual people appearing in the process of urban modernisation. Boris Klein writes in his memoirs that as early as 1966, together with Alexei Karpyuk, they tried to stop the demolition of a group of timber houses with late-baroque stone façades. They were in the late 18th century for workers building the Horodnica estate, along today’s Eliza Orzeszkowa Street near the writer’s house[5]. The complex (two three-house terraces) was to make room for the expansion of the railway square, but on the other hand it was supposed to vanish for ideological reasons. Klein writes that Karpyuk shouted at the foreman that he should suspend the demolition, which had already begun. When the foreman refused, Karpyuk went directly to the Secretariat of the Communist Party of Belarus. He managed to save just one building which was later restored and turned into the Museum of the New Town.

Unlike this unofficial protest, the leading art magazine of the Belarusian Socialist Soviet Republic, Mastactva i Literatura, in 1965 filed an official protest against the rebuilding of Grodno, threatening its historical fabric also in other parts of the city[6]. And so the meaning and value of an urban ensemble of the banks of the Neman was discovered not only by local enthusiasts, but by professional historians, ethnologists and archaeologists as well. Also, their colleagues from Minsk, working in various academic institutions, gradually amassed a detailed knowledge on the past of the territories now belonging to this Soviet Republic. Grodno was perceived in the capital not only as a quintessential European city, with narrow lanes as opposed to the broad avenues of the Belarusian metropolis, but also as a seat of former royal and ducal castles legitimising the grounding of Belarusian history in the European, and specifically Lithuanian context. Victor Govar, the editor of an architectural magazine, used all available means to stop the destruction of the historical fabric of the city and to find resources to restore its monuments. In 1965, comments and statements by specialists brought these threats to the attention of the public. Govar also pointed at the effects of intensified housing construction projects: all available resources were pumped into the development of new areas, while the restoration of the Old Town was claimed to be expensive with so many new flats needed. Govar not only appealed for a careful approach to the buildings in the city centre, but also perceived the architectural heritage of Grodno as a starting point for new Soviet traditions: “Such principles were formerly held by foreign masters. A detailed study of your own architectural tradition may produce many interesting discoveries. When used creatively, they will allow the city to find its own conception of designing modern interiors, façades, buildings and small architectural forms. The city would thus acquire an individual appearance.”[7] Although this comment was meant above all to point at a certain system of construction, which in the era of central planning and mass industrial production caused the new housing in the Grodno region to look almost identical as the new housing in Irkutsk or Tashkent, the article also appealed for creating an own new urban style in the architecture of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. Although the model proposed by Govar was the Kalozha Church, part of the Ruthenian cultural heritage, the context suggests that it was just an example to be broadly interpreted.

In the 1980s some residents of Grodno started to campaign for the preservation of particular buildings, even if it resulted in repressions in their professional life. One of the few stories with a happy ending – from the point of view of the activists – was connected with the need to find an appropriate space for the great annual parades organised by the local Communist Party. The Liberty Square – the representative focal point of the New Town, purged of all traces of Russian rule in the interwar period, with the Statue of Liberty knocked down by the Soviet administration in 1939 – changed its name to Lenin Square after World War II. The monument to the leader of the Revolution stood by an eternal flame commemorating the heroes of the Great Patriotic War, next to a theatre in a place where the palace of Antoni Tyzenhauz had been located until World War I. Lenin Square hosted important Soviet celebrations until 1955. Next year this all-purpose space was restored to its historical character of a market square. Meanwhile, the place where the former town hall once stood had been so thoroughly flattened that as a part of the Soviet Square it could accommodate a growing number of participants of May and November celebrations (in 1961 St. Mary’s Church – the most important Catholic church in Grodno – located also in the Soviet Square was blown up). The only representative Soviet building which remained in this place was the Palace of Culture of textile workers. A tribune for regional Party authorities was raised every year in front of it. This neoclassical structure served as the principal edifice in the city. But it was not enough for Party officials, looking for office space for the board of the municipal executive committee. A plan was conceived to fill up part of the city park Dolina Szwajcarska in the Gorodnichanka river valley. A larger and more representative square would be created, forming an appropriate scenery for the new seat of the executive committee. The new space was to be called Lenin Square. But the project was frowned upon by the local branch of the Central Archives of the BSSR, whose building was part of the New Town complex located in the middle of the planned square. The decision to demolish it provoked violent protests by groups of local intelligentsia, including employees of Soviet institutions, who faced serious consequences. This was the first so tense conflict with such symbolic ramifications. On one side stood the Party, which wanted to have a more representative seat and to that end it decided to bring down an officially recognised architectural complex of major historical significance for the whole Republic. On the other side stood people like Karpyuk, Gostev and others, passionately believing that it was an attack on their city, their culture and themselves[8]. While some wrote letters to higher places, Karpyuk allegedly went to the Party headquarters and scolded the secretary as if he had committed a crime of honour. He threatened him with occupation of the building if the decision to demolish it was upheld. It is impossible to confirm this story today, but the effects of the various interventions are still visible – the building has remained intact. Meanwhile, the Archives have acquired the status of National Archives and all historical documents on the region from before 1917 are still kept there. But the symbolic conflict has not been fully extinguished, for the larger Lenin Square, where the statue of the revolutionary has been moved, competes with the oval Tyzenhauz Square until today. The schizophrenic situation of a double square, divided only by a two-storey structure, symbolically reflects two different approaches of the Soviet regime to contemporary uses of historical urban space.

Another conflict broke out in 1986 during the construction of the new railway station. It was expected that this facility would fulfil the needs of the expanding city and the border crossing for international traffic – the historical railway line from Warsaw through Vilnius to Leningrad still led through Grodno. It had been decided early on that the late classicist building from 1867 would be demolished. Urban planners believed that it did not meet contemporary requirements and that a much larger structure was needed. To avoid the necessity of temporarily stopping the railway traffic, the new concrete and glass structure was raised so close to the stone building that they almost touched each other. In 1989, right after the opening of the new railway station, the demolition of the old one was launched. It met with a massive disapproval of many residents, but this time petitions, letters and protests were of no avail. University, administrative and museum workers, who felt responsible for the cultural heritage of Grodno, this time failed in their attempts at stopping the authorities.

In the same period a group of art historians, residents supporting preservation of monuments and urban planners created a project of safeguarding the historic fabric of the Old Town. It was not meant as a private act on the part of individual citizens, but another step towards creating an urban plan for the city centre. On the basis of similar projects for other Baltic cities, a restoration plan for the historic centre was put forward in 1989, very original in its approach to urban space. A successful implementation of the project could result in the inscription of the city centre on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Art historian Oleg Trusov and his colleagues decided that the entire historic city space of Grodno should be endowed with the status of a museum. It was to be preserved in the state from the late 1980s. This would prevent further damage and enhance the value of the entire complex. When a city acquires a museum status, all its sites become artefacts. All that should be protected speaks for itself, but this does not concern every existing detail, but only the elements regarded as old. The Soviet signs of disgrace were excluded from that list, for example. Since a museum is to be understood as a cultural space inspiring the sense of identity, the project proves that the city itself has become an impulse for a new Belarusian urban tradition. Like with a palimpsest, reading this space required discovering and recreating the multiple historical layers. In this way the seemingly hidden strata were unveiled and made visible.

Also, today there are many residents committed to displaying and safeguarding the relics of the past which were hardly recognisable before 1991. They hope that the omnipresent Soviet texture will gradually fade or be replaced by a “post-Soviet” one. Despite the policy of intimidation and repression, there is a small community of students, academics, teachers and pensioners ready to be involved in restoration efforts above the level tolerated by the authorities. Their main concern is the “reconstruction measures” damaging the historic fabric of the city centre. Buildings requiring renovation, such as a storehouse by the railway tracks or a house in the former Jewish district, are demolished and then rebuilt using new materials and floor plans, with the façade giving an impression of historicity. A two-storey house rapidly morphs into a three-storey one. Residential houses behind the town hall, raised in the late 19th century, are removed from the centre of Grodno, for their appearance may produce an impression of a poor and overcrowded city, which is not an image desired by the authorities. During the construction of a tram line archaeological work is hindered or so superficial that precious information on the city’s past is lost forever. In 2006 there was a protest against the construction of an underground passage at the historic main square, which damaged the foundations of the town hall, brought down in 1944. When we are talking about saving relics of the centuries-long past, accumulated in the soil from destruction by heavy-duty equipment, the notion of a palimpsest becomes something more than just a metaphor.

Another challenge for the activists gathered around the harodnia.com website are the interwar estates in the Nowy Świat district, threatened with demolition. The timber villas in a European style reveal marked Polish influences. The fusion of regional construction methods with forms characteristic for Modernism is unique in this part of Europe, both in terms of quality and the number of buildings. Distinct lines of Formalism, popular in Poland in the 1930s, combined with elements of local style, indicate that the western part of today’s Belarus, hovering between the influences from Moscow, Warsaw and Dessau, belonged to Central-European Modernism.

In the eyes of a foreign visitor these streets appear as even more worthy of protection. But locally, they are often regarded as a useless burden taking up valuable building ground. The buildings are in a bad state of repair and only the instability of the capital market and poor economic growth in the region temporarily prevent a quick transformation of the district. The few residents aware of it, such as Andrei Washkevich, warn against this danger and try to prevent further damage through workshops, publications and social campaigns. But they have to deal with other citizens, who do not understand and do not respect the value of particular buildings and architectural ensembles. The city authorities have little understanding of such actions and brand them as dissident.

Inscription of buildings from the 1920s and 1930s on historic monuments list seems almost utopian, despite the fact that they require urgent measures, regardless of whether they belong to the Polish, Jewish, Russian or Belarusian history of Grodno. Washkevich and other residents call the actions of the authorities an attack on their city and a proof of their miscomprehension of historic values. But, because of the intense conflict about further modernisation of Grodno the city space will remain part of the palimpsest: a place where history may be comprehended spatially and functions as a symbolic signpost revealing the various layers of the past with the help of science. For the residents, but not only for them, the city of Grodno will remain an important point of reference defining their identity and inscribing them in the urban texture.

***

[1] Химик, 3 June 1983, p. 4.

[2] В. Кудряшёв, Гродно, Минск 1960.

[3] И. Шамякин, Гродно, Минск 1989.

[4] А. Гостев, В. Швед, Кронон, Гродно 1991.

[5] Jurij Gordziejew, “Próby przekształceń miejskich w Grodnie w epoce Oświecenia”, Rocznik Biblioteki Naukowej PAU i PAN w Krakowie, 2001, pp. 227–257.

[6] В.Говар, Архiтектурная старонка, Мастацва i Лiтература, 30 June 1965, pp. 11–12.

[7] Горад двух вымяренняў, in С.В. Марцэлеў, Збор помikaў гисторыи и культуры Беларуси. Гродзенскае вобласць, Минск 1986, p. 3.

[8] Interview with M.A. Kachov, Химик, 21 April 1989, p. 2.

Copyright © Herito 2020