Culture and Politics

Protest Art

Publication: 11 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESA good and effective strategy in politicised art may bring about specific social results both for the artists/political technologists and for the recipients. Sometimes these results also have an artistic dimension.

When a resolution regarding the introduction of military sanctions against Iraq was voted on at the United Nations, the appropriate US authorities ordered Picasso’s Guernica to be covered. A work of art as a protest against violence can have the power to be a unique historical message, and may serve as an accusation against a political regime. The power of art is as attractive as any other form of power. The question is, how does the work achieve this power? Is it thanks to its perfection, as it was once thought? Or thanks to the impact of mass media, for which art is an information pretext?

Protest art belongs to the popular specialisations of contemporary artists. It emerged in an institutional form at the end of the 1960s, and 1968 revived the “revolutionary creation of the masses”. Its organisers and ideologists were well-known artists, such as Joseph Beuys and Carl Andre. A year later, Andre, Lucy Lippard and the German neo-Marxist, Hans Haacke established the Art Worker’s Coalition, which had a political demand and acted as a trade union to challenge museums to offer exhibition space for non-white American artists, and created a subgroup called Women Artists in Revolution (WAR).

Haacke adopted the image of being a critic of imperialism and exposed the ominous role of capital – including museum foundations which enhanced the reputation of businessmen and politicians – in the social functioning of art. In 1971 he approached the Guggenheim Museum with an individual exhibition, Hans Haacke: Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, which exposed a real estate scandal. The exhibition did not end up taking place. A Real Time Social System is composed of 140 black-and-white photographs and documents of old brown bricks in the centre of New York, bought by a businessman called Shapolsky, who evicted the tenants, razed the buildings and sold off the expensive plots of land. The Guggenheim Museum never officially explained why it abandoned the show, but there were unofficial suggestions that presenting the dilapidated houses of shabby districts would be in bad taste, despite leaflets advertising the exhibition already printed for distribution. The curator of the planned exhibition was later fired. Haacke’s work belongs to the canon of art history, and Haacke acts as an objective documentalist, a sort of investigative journalist. The photographs and documents conceptually placed on the wall of a museum, as if they were on an office wall, are not an object of aesthetic criticism. Haacke attempted to present artistic practice as an element of successful political struggle. He argued that an artist shouldn’t use any special professional tricks which would hamper the reception of his work. In 1974 Haacke presented documents revealing the financial interests of the sponsors of the Guggenheim Museum in Chile. These interests were threatened by the reforms of Salvador Allende, which may have led directly to the coup and the death of the president. Four years before Haacke presented these documents, the harmful activities of American corporations in Latin America were challenged by the Brazilian artist, Cildo Meireles, in a peculiar way. Meireles collected empty coca-cola bottles, put a new inscription on them and sold them back to a recycling facility, from where they found their way back to the factory and then back into the shops. The first inscription read: “Yankees Go Home” (Insertions Into Ideological Circuits, 1970).

The political artists from the 1970s were victorious in a certain way due to the fact that their colleagues, regardless of the colour of their skin, achieved the opportunity to display their work. In another aspect, however, the triumph of political art (and conceptual art, to put it more broadly) proved futile: it is doubtful that anyone will ignore Haacke’s work abroad fearing that it might put a stop to illegal dealings on the real estate market in Moscow or St. Petersburg, for example. Equalling political protest actions with works of art makes them become abstract, as it is only their artistic or aesthetic aspect which is important in the long-term perspective. If Picasso had not told the eternal historical drama – as presented on the vaults of medieval Catholic churches – in an expressive contemporary language, the town of Guernica would be known as one of the innumerable places of war and disaster, rather than a challenge and appeal for the instant activation of historical memory and reflection. In the late 1970s another feature of political art penetrated social awareness: the direct participation of artists in politics cannot solve social problems or reveal new truths to the world, as the idea of progress loses its specific character here and the objects of the struggle – freedom and humans – are treated in a very ambiguous way. Society prefers “simply to live”, leaving political activity to its representatives; indifference to the truth borders on the readiness to justify any unjust act, unless it does not concern at least every tenth member of society, as was the case with the wars in Vietnam or Afghanistan. Therefore it becomes necessary not to be mixed for the social situation and consistently avoid it in all its contexts.

In the history of Soviet art, the 1970s were a period in which anti-Soviet artistic movements, such as Soc-Art, were formed. It was the political struggle which drew attention to what was happening behind the Iron Curtain: for the first time in many years the American press took note of an event in Soviet visual arts, the so-called “bulldozer exhibition” which took place in September 1974, when police, equipped with bulldozers, chased away ten artists who had organised a street exhibition on the outskirts of Moscow.

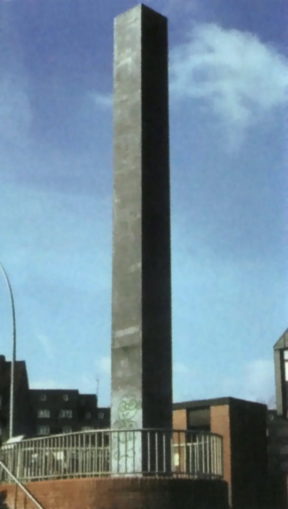

Political art in the 1980s was reminiscent of the helpless prophecies of Cassandra. In 1986, Jochen Gerz and his wife, the artist Esther Shalev-Gerz, created an anti-Fascist monument in the centre of Hamburg – a twelve-metre obelisk in a lead sheaf, with a protest against violence inscribed on the sides in seven languages. The artists placed it not only in space but also in real time: a special mechanism lowered it down very slightly into a trench each day, until 1993, when the earth finally absorbed the monument and the trench was covered with bullet-proof glass. The inhabitants of Hamburg and tourists were able to write their reflections about war and violence on the obelisk for seven years. Around 60,000 contacts with the monument were recorded, although only some of them were actually anti-Fascist. Many advocates of violence splashed the obelisk with paint, scratched away the text of the declaration, drew swastikas and even shot at the monument with large-calibre weapons. And it was with this record of the destructive actions of decent citizens that the monument vanished into the earth. The story of Hertz’s obelisk proves that “simply living” by society does not warrant social peace or happiness.

When the Soviet system collapsed in the late 1980s, a calming effect of “the end of history” briefly appeared in social awareness – as if one political problem had suddenly vanished. Art in Europe and the United States spoke about the devaluation of the evolutionary Modernist spirit. Politicised actionism moved to Moscow, where political life erupted with a new force – as opposed to Soviet times, when it occurred mostly behind the scenes. Art in Moscow between 1992 to 1995 fully belongs to actionism. Among its leaders were the “man-dog” Oleg Kulik, who had worked with the Regina Gallery since 1993, and Anatoly Osmolovsky, who jumped on the bandwagon of Damien Hirst’s popularity and copied some of his scandal-seeking works (photographing himself with the head of an old lady’s corpse); another role-model for him was Vladislav Mamyshev (a portrait without trousers).

Between 1994 to 1995, political art invaded the streets of Moscow under the project Art Belongs to the People. According to the eminent expert on the avant-garde, Andrei Kovalev, you can see “sanitised” or weakened protest art with artists who start to assume the role of media stars entertaining the public: “The project […] provides for the use of billboards on which the unsuspecting public sees specially prepared works of contemporary artists. […] On the semantic fields of new Russia, advertising replaced political propaganda […]. As the fundamental aim of the project the catalogue names the ‘expropriation of new areas of art’, which looks like assimilation of the activities of the revolutionary group ETI (short for Ekspropryatsya territory iskusstva – Expropriation of Areas of Art) under the direction of T. Osmolovsky, and therefore the revolutionary element of the project as an aesthetic category is not original. But previously, the revolutionaries carried out their provocative and terrorist actions without coordinating them with the representatives of the oppressive classes. This means that the revolutionary movement entered a new stage: the petty hooliganism of old has become a thing of the past and wholesome revolutionary cynicism now allows strategic cooperation with the mechanisms of bourgeois oppression. Only by infecting – like a computer virus – the channels of mass communication may the contemporary artist bask in the triumph of destruction …”[1]

Two dominant tendencies can clearly be seen in the second half of the 1990s and in the beginning of the next decade. Firstly, protest art aimed at a “strategic cooperation with the mechanisms of bourgeois oppression”, that is the government and the media, assuming the role of a scandalising information pretext and becoming “p-art”, which organised small and medium-size provocations. Secondly, its strategies were successfully adopted by unknown “artists-bureaucrats”. As the years went by, the number of reverse provocations and acts of violence against politicised artists grew: the mayor of New York stops an exhibition of British art called Sensation, the artist Avdei Ter-Oganyan is repressed in Montenegro and Moscow, the exhibition Attention, religion! at the Sakharov Centre is destroyed, the “caricatures scandal” erupts in European and Islamic countries, and even finds an echo in the small-circulation Russian press, exhibitions at the Moscow Guelman Gallery are attacked three times, and during the third attack the owner is physically assaulted and speaks to journalists with a bloodied nose and bruised face. In most cases – excluding the last one, which was probably associated with the anti-Georgian campaign (the works on display, destroyed in this act of violence, were by Alexander Dzhikiya) – both sides use religion as the catalyst for political (and pseudo-political) struggle. In the Islamic countries and Russia, religious power either dominated the secular power or subordinated itself to it, while in the United States the resurgent spirit of Americanism is inseparably connected with the history of the belligerent Reformation, and therefore there is little wonder that the principles of religious morality were the first victim of the political game called, “tough state and religious leaders of various countries against the liberal-Bolshevik conspiracy”. Protest art as a religious and political provocation becomes dangerous for all of its participants: artists must escape abroad, curators are taken to court and fined, and the greatest risk is for the government, whose policy may turn everything around into a multi-confessional Taliban.

The first to speak about strategic changes in protest art were the visual artists and writers working with Marat Guelman, known for their artistic practices between 1970 to 2000. Also worth mentioning here is Dmitri Alexandrovich Prigov, who published poems in the Soviet samizdat, and Dmitri Gutov, who, in the 1990s, was an protagonist of Mikhail Lifshyts, the Soviet philosopher and guru of Marxist aesthetics. On the occasion of the Russian flagship artistic event in 2005 – the First Moscow Biennial – Guelman opened an exhibition in the Central House of Artists and published a magazine/catalogue entitled Russia Two. Russia One is a country which lives in accordance with Putin’s commandments. Russia Two is a private territory whose inhabitants have broken all contact with the regime, with politics tangled up with the economy, and with the media and celebrities. Moreover, Guelman claims that Russia Two is not an alternative to Russia One, it cannot be categorised in such dissident terms as anti- or counter-. It is the profoundly internal reality existing here and now, a virtual base of ideas, which is able to function because of the fact that contrary to Brezhnev’s influence in today’s Russia One, there is no room for a political anti-government movement, there are no communities sympathetic to the cause: the people and the regime have become one, and they are ready to march hand in hand and “protest for”.

Gutov says that artists feel isolated, both in the “large progressive streams” of the liberal discourse and in the vertically organised power of the post-Soviet elites. Today’s artist is destined for a “cottage in the mountains with a hole-ridden roof” and his or her task is to “improve his or her image by visual means”. Some works at the Russia Two exhibition were more poignant than the ones shown at other venues of the Biennial. They stemmed from the personal experiences of the artist, gained in various situations and revealing a direct, “organic” experiencing of reality. It may have been the experience of an involuntary migrant or a “rank-and-file” viewer of television, who does not want to have his or her awareness muddled. One way or the other, the personal experience of the artist makes the work a social rather than “institutionalised” act of protest. In the multimedia installation by Aristarkh Chernyshev, a collective portrait of contemporary television called Dirt for Chewing, and in the abstractions of Ter-Oganyan, where colourful geometrical forms work as a parody of the absurd interferences of censorship, a natural protest against the lie imposed from above achieves an active artistic expression.

Russia Two attracted the attention of the public and its curator, Guelman soon became a leading figure of the so-called “systemic opposition”, which is this segment of politics where supervised critical pronouncements are allowed. Curator Andrei Erofeev, who cooperated with the Sakharov Centre, was fired (from the Tretyakov Gallery), while Guelman became founder and director of the Perm Museum of Contemporary Art and the main “cultural ideologist” in the research centre in Skolkovo, which is under construction and intended by president Medvedev to provide Russia with a new generation of scholars, as well as stopping the process of “brain drain” in Russia. Guelman’s career had no bearing on the situation of the most talented artist from his gallery, Ter-Oganyan, who for more than ten years has been hiding from the Russian authorities in Prague and Berlin (he was taken to court for his participation in Erofeev’s happening A Godless Young Man, which consisted of destroying Orthodox icons made of paper). Gutov rejected the status of cultural outcast and together with the rich Moscow collector, Vladimir Bondarenko, organised an exhibition of paintings in Guelman’s museum – the exhibition could be likened to a simulacrum of social advertising regarding ethnic tolerance. With his characteristic handwriting, he inscribed on canvas the ethnic origin of great scholars, painters and musicians, the brightest stars of world culture and science.

A good and effective strategy in politicised art may bring about specific social results both for the artists/political technologists and for the recipients. Sometimes these results also have an artistic dimension. The aesthetic or visual criterion of artistic quality has been surreptitiously replaced with effectiveness and social success, although this criterion still exists and determines the status of a work in art history. For example, the happening by the VOINA Art-Group (“War”) – who painted a phallus on the Liteiny Bridge in St. Petersburg, opposite the seat of the Federal Security Service, was widely spoken about thanks to its visual distinctness and obviousness of the image, as well as the effect that the raising of the bridge had on the image.

I want to end this story with a rare example of true protest art – a pearl in the crown of street art. In August 2007 anonymous graffiti artists from St. Petersburg sprayed the text of a poem by Bertolt Brecht in the entrance to a huge department store built during the Brezhnev era. On this particular day, the rectangular buttresses of the entrance, which are usually covered with bright tiles, were changed into the pages of a notebook for all those going back home from the metro station, successively revealing the truth about the readers themselves and the present situation of the Russian metropolis. This work of civic protest, perfectly inscribed in the urban fabric, survived just a few hours. The store’s administration, usually tolerant of various graffiti experiments, even those which sometimes have a nationalist content, this time expeditiously liquidated the art which spoke with an honest voice. History, however, which does not teach anyone anything, is still astonishingly capable of defending itself and putting itself on record – in the memory of mobile phones, for example.

2006, 2011

***

[1] Andrey Kovalev, O revolyutsionnoy sushchnosti mantry Avalokiteshvary, in: Isskustvo prinadlezhit narodu, ed. Aristarkh Chernyshev, Rostislav Egorov, Anna Panova, Moskva 1995, pp. 11–14.

Copyright © Herito 2020