Symbols and Clichés

The Art That Wasn’t Here

Publication: 17 August 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLES“If a visitor is delighted at finding forms familiar from his own ground here, it will be athoroughly positive experience. It will not be so good if he attempts to turn this into a political argument to suit his current needs. Art as alleged validation of political programmes was a disturbingly common feature of the totalitarianisms of the 20th century.” This warning, noted down by Prof. Ewa Chojecka in the preface to Sztuka Górnego Śląska [Art in Upper Silesia], is applicable to many regions of Central Europe. Themore precious, thus, is the experience of these Katowice scholars, showing how to extricate an image of the region and its art from the distorting mirrors of nationalisms and stereotypes.

Łukasz Galusek: At the time when you started work in Katowice, in your own words: “the 19h and 20th centuries were blank spaces; there was no knowledge of what was of value here in Upper Silesia.” 2009 saw the publication of the second edition of the impressive Sztuka Górnego Śląska [The Art of Upper Silesia], which you edited. I would like to ask you about the road between those two points.

Ewa Chojecka: The book is a collective work by employees of the University of Silesia’s Art History Department, who arrived in Katowice in the early 1980s with the uneasy thought: “Well, but what am I going to do here? There’s no art here.” And, it transpired that our interpretation of the region’s artistic legacy coincided with vast methodological changes in art history, which was opening up to the heritage of the 19th century and to 20th-century issues. Notice that in the venerable Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce [Catalogue of Historic Artworks in Poland], published by the Polish Academy of Sciences, on principle the very latest works that were included were from the mid-19th century. No examples of historicism were included; only late classicism if anything. Yet, in Silesia it was in that period that everything was just beginning. As such, the bulk of the local fabric was not even noticed. This even includes buildings such as residences. Yet, we have discovered a wonderful, truly European historicism here, inspired by the French style and by Schinkel, that produced a whole series of splendid architectural solutions – except that they were subsequently burdened with the anathema of being “Prussian”, and hence deemed not worthy of interest.

Add to this politics, in this case the rules as to what scholars were to work on. We had to circumvent this doctrine entirely. We decided to adopt a completely different criterion – whether or not something was good art, and in addition without paying attention to its national provenance. Our decision proved right. In time, elements that we had not initially noticed came to light, which had been camouflaged by a mantle of propaganda concealing every iota of authentic value in the works here.

There was also a stereotype surrounding industrial architecture which, until recently, was considered solely utilitarian. In fact, this is a whole separate issue itself, especially in Upper Silesia. The construction of the new home for the Silesian Museum in Katowice seems to me to have taken on almost symbolic magnitude – not only as a complex coming into being on the site of a former mine, but also as a new architectural design incorporating some of the mine buildings. This new sensitivity pleases me.

Ł.G.: The breakthrough that came in 1989 brought the potential for “regional thinking,” as an antidote to the centralisation and rule by top-down decree symptomised by things like the research rules you mentioned. But, I think it brought something more: a start on the road to subjectification, to appreciating things there had been no room for in the previous canon.

E.C.: That is true not only of Silesia, but of more or less every region. Unfortunately, we are still prone to thinking in centralistic categories. The authorities are still afraid that some of their decision-making powers will elude them, though I don’t know why. I find it sad that regionalisms tend to be used as a tool to antagonise people. This was something else we had to fight against. And suddenly, the people of Silesia saw that it is not just a coal-bearing desert. The art they had been told they did not have raised their status, and they gained the feeling that their native cultural soil was very special, and that they themselves were participating in its discovery.

I was surprised by the fact that Sztuka Górnego Śląska has a function as a history textbook, which was not the intention – but if there is no other? Regional education is evidently still poor in Poland.

Ł.G.: Tell me about work on the book itself. (Maybe: What did the work on the book itself look like?)

E.C.: It wasn’t easy. First of all came the problem of selection, which on occasion was very painful, that is what to reject, because we had to keep to some kind of sensible volume. Secondly, there was our modest budget. Our grant from the Scientific Research Committee covered travel, camera film and accommodation. The Silesian Museum, which was publishing the book, also had to find funds for the paper, the printing, and other aspects of the publishing process. But we were guided by something far more important – our great love for our subject and for our research work. This is a kind of gift that enables us to treat our work as a vocation,and then no effort seems too great.

We said to each other: we have to tour the region, there’s no other way. We had to experience the site in situ, to have a picture of what the whole really looks like. We held seminars at the sites, the four of us: Irma Kozina and Barbara Szczypka-Gwiazda, Jerzy Gorzelik and I. We debated, because essentially we had no background materials; we were operating entirely without inventories.

Ł.G.: And what’s more, the geographical area of your study crosses state borders, because it takes in the Czech part of Silesia too.

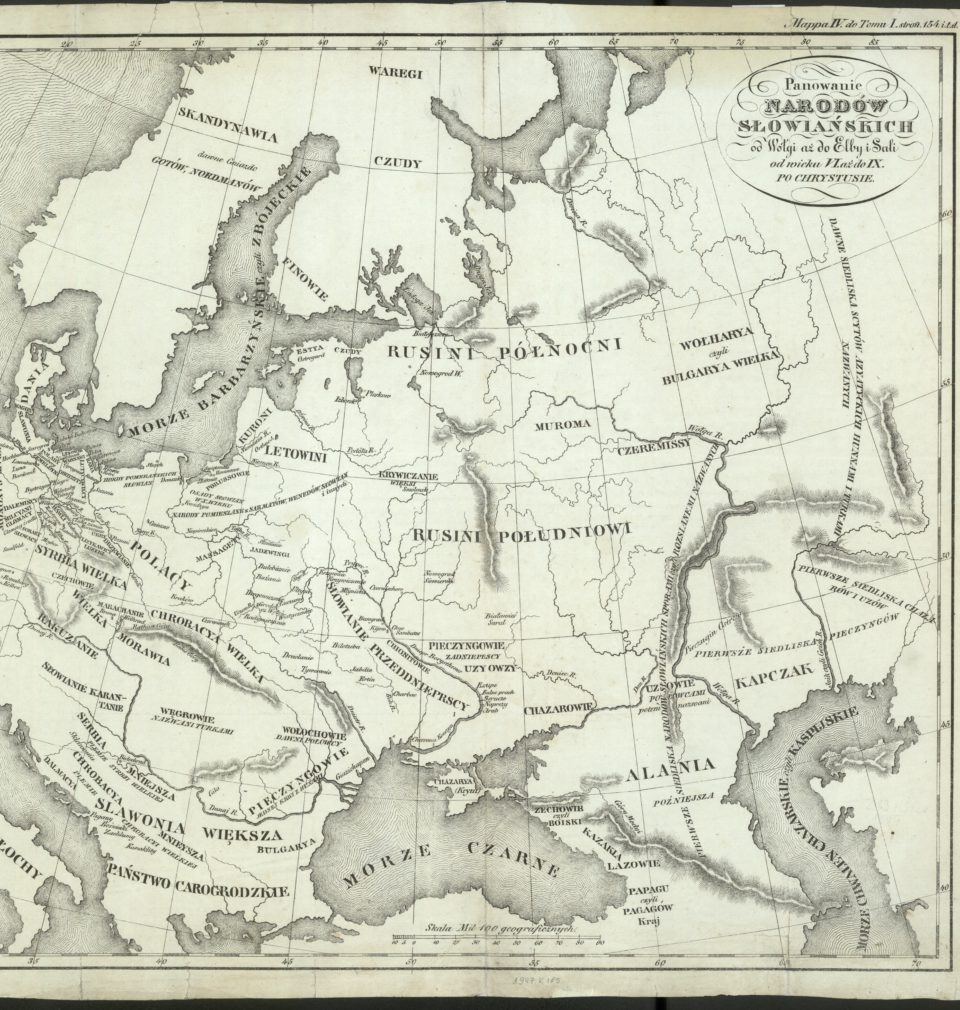

E.C.: And then there are nuances such as the unique nature of Austrian Silesia in the south and Prussian Silesia in the north. Who can still tell them apart today?! It was only by including maps that we were somehow able to illustrate these things, because historical Silesia can’t be restricted to just one country.

Unfortunately, borders used to be insurmountable obstacles, which is the reason why we know so very little about Czech Silesia. Yet, this is real Central Europe – a truly international region. And, how strangely these borders have changed! First the Piasts, but as vassals of Bohemia. They were closer to Prague than to Krakow. Then came the Habsburg rule, until the end of the Silesian Wars brought a more permanent division between the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (in the south) and the Kingdom of Prussia (in the north), which shortly became the Hohenzollern empire. And then came the 20th century and real revolution, with the post-World War I divisions, the conflict with Czechoslovakia, with the Weimar Republic, the drama of the Third Reich, Yalta. How to compile a coherent whole from that bizarre puzzle, tell me?

We came to the conclusion that the only way was to take a sovereign approach to the artworks, to treat them as a value in themselves, something that exists independently of political organisms and historical circumstances. Sine ira et studio was our motto, and it produced a superbly rich cultural landscape – Czech, German and Polish.

Ł.G.: Can we go back to the start of your academic road? Who were your mentors?

E.C.: I started studying history of art in 1950, during the very difficult period of Stalinism which was also a time of material poverty. History of art was an enclave of freedom, because it was considered a subject for pretentious aesthetes who were not worthy of attention.

At that time, my academic interests lay in prints, books and illustrations; the art of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. This was my area of study at the Jagiellonian University Museum, and later at the Jagiellonian University’s Institute of Art History. Until the opportunity arose for me to enter a competition for a Ford scholarship to go abroad. An incredible chance, not like it is today. And, I was awarded a year’s scholarship in England, at the Warburg Institute. Having obtained the foundation of an education in my field at the Jagiellonian University – my Master’s degree and my doctorate – I gained an European perspective on the history of art there. I owe most to Ernst Gombrich, the director of the institute. That charming gentleman, from Vienna, forced to flee from there to England in 1938, had grown into the English culture. He spoke beautiful English with a delightful Viennese accent. It was he who opened my eyes to matters of the psychology of art, which was then still entirely unknown here. He was working on Art and Illusion and The Sense of Order, on the psychology of ornament. In this, the iconological layer developed by Aby Warburg was enriched by a kind of a second level, Gombrich’s own conception of the reception of a work of art through the eyes of the individual and his or her sensitivity, which is conditioned culturally, historically, and in many other respects.

I arrived at the Warburg Institute, which welcomed guests from Eastern Europe with immense hospitality and kindness, full of fears, not to say terrified, as to what it would be like. In fact, I was treated as a younger colleague, a discussion partner, which at that time overwhelmed me – in Poland it would have been unthinkable. It is that approach to young people devoid of any feudal distance that I recall with most gratitude. My experience at the University of London is a great treasure which I still draw on today.

Ł.G.: From London you returned to your work in Krakow. Where did Katowice come into it?

E.C.: After I qualified as an assistant professor the opportunity arose for me to work as an independent academic in Katowice. It was a leap into the unknown, but I risked it. It was 1977. A seemingly trivial scene has etched itself on my memory. I was on my way to the rector’s office to submit the relevant papers. I was waylaid by an administrative employee, who asked me, in that characteristic accent: “Have you brought those papers, Ma’am?” It’s only here that sentences are spoken with that unique lilt and smile. All at once, I realised: “Ewa Chojecka, you’ve come home!” Shortly afterwards I found out that people had been gossiping about me, as they do when someone new arrives on the scene. And, the Silesians had been saying to each other: “That Chojecka, she’s one of us, you know.” (Laughs). A kind of acceptance. It’s funny how sometimes a trifle can encapsulate the whole atmosphere of a thing, though at first we don’t recognise it.

And after that came some very hard graft, because I had to completely rework my research technique, everything. To start doing something completely different from before. What I had walked into. And that’s how my whole adventure started. And so, wasn’t it a good idea to come to Katowice?

Ł.G.: But your work went far beyond your office.

E.C.: I’m pleased we managed to graft art history onto the tree that is Katowice, and onto its bare roots at that. But we also succeeded in doing something else, also very important – reviving the Silesian Museum, which had been destroyed during the war and had since been almost completely forgotten. We started working towards this in 1979, 1980, during the first wave of Solidarity. The establishment of the Department of Art History and the foundation of an Upper Silesian Division of the Association of Art Historians were the first steps in building a professional community here, one capable of formulating opinions and conducting debate with the aim of calling for all manner of changes. We were effective enough to bring about the restitution of the museum in 1984. This was the period just after Martial Law: poverty, economic collapse, and at this point, which might have seemed the least opportune, the museum was once again linked into the region’s cultural circuit. It might seem comical, but sometimes if I’m walking along Korfanty Avenue in Katowice I will stop young people with the provocative question: “Excuse me, is the Silesian Museum in this building?”. “Yes, yes, it’s always been here”, they answer, to my great delight. And isn’t that how it should be?

Ł.G.: In the context of the museum we should mention its founder, Prof. Tadeusz Dobrowolski, whose seminars you attended as a student in Krakow.

E.C.: The museum was his life’s work. When he came here after the war to rebuild it, he was treated as a harmless idiot and sent packing. In Krakow he mentioned nothing of his time in Katowice; he never spoke of the Silesian Museum, not even the name Katowice was mentioned. Fear of some kind of political complication kept his mouth shut. The museum had been the flagship project of Poland under Piłsudski, personified in the figure of the voivode, Michał Grażyński. And, here we come up against the problem of the negation by the Polish People’s Republic of the civilisational and cultural achievement of the Second Republic, and the issue of the autonomy of the voivodeship of Silesia. The sum of his cultural work was considerable. In architecture alone, the Castle of the President of the Polish Republic in Wisła, Katowice modernism, not to mention the architecture of the museum itself. The Silesian voivodeship invested in modernity to an unprecedented degree, yet this was muffled by an official conspiracy of silence. My colleagues from the institute and I put a lot of effort into restoring not only the memory of Prof. Dobrowolski’s work in Silesia, but also the awareness of interwar modernism.

That was the beginning, and time proved that there was no shortage of difficult subjects that had to be tackled. The legacy of the People’s Republic of Poland is not black and white. Take, for example, architecture that can’t simply be dismissed as “bad socialist”. The “Spodek” [lit.: “the saucer” – a large sports and entertainment arena] in Katowice, for instance, or the Henryk Buszko and Aleksander Franta estates, cannot be dismissed as run-of-the-mill socialist. And what of the artistic community? Grupa ST-53, and the artists active here after 1953? Again, generalisations are not enough.

Ł.G: Upper Silesia clearly specialises in works that can’t be pigeonholed into a single tradition.

E.C.: People here have a certain instinct for modernity. What is more, it comes through even in adversity. This course for modernity was first set in around 1890. Hans Poelzig arrived here, for instance, and created some excellent industrial architecture. And what about Emil and Georg Zillmann, with Giszowiec and Nikiszowiec? Nowadays it’s even something of a status symbol to live in “Nikisz” (laughs).

The landscape became more densely populated over time, and a diverse, but very complex, multifaceted and very genuine whole developed. In what used to be Austrian Silesia one can still feel that Viennese “fleur”, and in the north there is something of Schinkel. And between them, the Pszczyna forest with the castle of the Promnitzes and Hochbergs in Pszczyna itself. The Hochbergs were landowners endowed with this same instinct of modernity. They sensed the advent of an era when they would have to reorient themselves towards industrialisation, manufacturing, mining – and reoriented themselves. They no longer made their fortunes from the Pszczyna forests but from large-scale industry – mines and foundries, the modern economic structure that they created in the Katowice region. And, they were not the only ones: there were the von Donnersmarck Henckels – both lines, the Protestants and the Catholics, the Tiele-Wincklers, and the Giesches. It was these families that laid the foundations for large-scale industry in Gliwice, Zabrze and Bytom. Today this chapter is coming to a close. That is by no means to suggest that everything linking Upper Silesia with similar places elsewhere in Europe – such as Westphalia or the Ruhrgebiet – should automatically be turned over to the historians. On the contrary. The developments in the Essen Zollverein, the post-industrial complex honoured as a UNESCO world heritage site and in addition this year’s European Capital of Culture, opens up the field for fascinating new ideas and poses questions about the future. Post-industrial tourism? Why not? Take a trip to the Guido mine in Zabrze – it’s a fantastic experience. Or the Queen Louisa mine – ask anyone in Poland who Queen Louisa was – a king’s ransom to anyone who can tell you (laughs)! This is a new perspective, a new take on the post-industrial heritage, where a former water tower, a beautiful, sturdy structure, is converted into lofts, and a pit head and winding gear are the logo of the new Silesian Museum. Well-known, universally recognisable spatial forms are being reformed in a new function and with a new message. And the Silesia City Center complex? Commerce is also moving into former colliery areas and transforming them in its own image. And the symbolism of the slag heaps and the “familoks”, the miners’ housing complexes unique to Silesia, a rich theme in both literary and spatial terms. And then the painting! The catastrophic visions of Bronisław Linke, the industrial landscapes of Rafał Malczewski, and then the art of the Janów artists, and finally Jerzy Duda-Gracz. I could go on and on, but these are difficult topics – and certainly not in the “Polish national style” of Wyspiański’s Wedding.

Ł.G.: This is a rather unfamiliar terrain, and so you have often had to explain the cultural difference of Upper Silesia. “From the perspective of Polish imponderabilia,” you wrote, “Silesia is not the stuff of myths.”

E.C.: We owe it to Silesia to restore its identity. This provokes fears, because no-one really knows how. I have no recipe myself.

Take some place like Bruntál, for instance, in the part of Silesia that falls within the Czech Republic’s borders today. It’s a Renaissance town with a beautiful castle – a Teutonic castle dating from the post-Grunwald period! The Teutonic knights were thriving as well as ever down there. (In fact, they survived there until 1945.) They were an order similar to the Maltese knights – a snobbish, aristocratic elite devoted to charitable work, which they performed very well. Among their grand masters there were even Habsburg archdukes, which is something that gets forgotten in Poland, because we tend to be in sway to another stereotype – that the history of the Teutonic knights came to an end with the Prussian homage. Yet, in fact they carried on their work in the Habsburg state. (Over time, some of them converted to Protestantism, but that’s a different story.) And you can’t deny them their good works, only our historical stereotypes have no space for those.

Ł.G.: We won’t find any traditional Polish noble manor houses here – no Sarmatian nostalgia. What we do find in terms of architecture is work by architects of European, if not world class. You’ve already mentioned Hans Poelzig and I would add Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut and Max Fabiani, of those who worked here. Josef Maria Olbrich and Leopold Bauer were also natives of Silesia. How to come to terms with this bipolar set-up? No-one wants to feel an outsider in their own region.

E.C.: I think we can learn a lot from Wrocław and how it assimilates and incorporates this “alien” heritage. Wrocław (Breslau) virtually ceased to exist as a city in 1945, there were none of its native townspeople left and it was being repopulated by new people from the East, from Lwów (Lviv), the few who escaped the carnage in Volhynia, and borderlanders with a pioneer mentality. And, what has happened in the second generation? I was once talking to young Wrocławians about Wrocław’s classicist architecture (from the first half of the 19th c.). At one point Carl Gotthard Langhans was mentioned, and one young architect said this: “Our Langhans”. Our Langhans! The designer of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, of Prussian classicism, is also his Langhans.

We have to rise above xenophobia and provincialism. There’s no other way. And, I think the people of Wrocław have understood that. For whatever reason, history suddenly washes people up in unfamiliar territory without asking them whether or not they want to be there. And, are they to throw out everything they find there? They have to work the land, sow crops and plant potatoes, so can’t they do the same with culture? That’s what happened in Wrocław. But it did take time, and a different system to the People’s Republic of Poland.

Ł.G.: It reminds me of Kazimierz Kutz, who used to talk of his work to painstakingly patch together, bond Silesia and Poland, that this was the essence of his efforts, everything he did. And then the care he took to ensure that the benefits were mutual.

E.C.: That’s why I believe that we will best serve Silesia’s affairs if we stand not within it but on the outside. If we look at them from the side, we will see them in their entirety, more fully. This is how I would supplement Kazimierz Kutz’s view: a certain distance gives a suitable perspective and enables us to judge more realistically, and without the feeling that we are always hard done by. If we look at ourselves from the outside, we see that it’s not all that bad.

Ł.G.: And taking matters into our own hands. Kutz criticises the Silesians for being “lumpish”.

E.C.: He is rather acerbic; I would prefer to speak of a need to preserve a certain distance. Some things are worth breaking a lance over, but in other matters common sense and distance is called for, even when the media is kicking up a storm all around. We have seen a lot of overzealous nationalisms here, some of which have taken drastic form and beaten people down. It’s just not possible to erase the injury, devastation and terrible experiences of wartime from memory. There are still problems that have not been psychologically disarmed, which are passed down in family lore from generation to generation. That is why people from this region are characterised by a “minimalist” approach to life – they see no point in putting their heads over the parapet. And that, in turn, is why so many of their talents go undiscovered. I’m sure the establishment of universities and colleges has done much good. But, even this came about in an absurd situation – the University of Silesia was founded in the worst of all possible years: 1968.

Ł.G.: In many people’s opinion the year Poland’s universities failed…

E.C.: Yes, and what was it intended as? “A hothouse for party personnel”! Well, it’s some “hothouse for party personnel” (laughs). That university started off not from ground zero but from below zero. And yet it’s a normal university. Because as a community of people, a universitas, in terms of a certain – in particular interpersonal – atmosphere, we might compare it to what the British call red brick universities. The political programme evaporated at the very start, thanks to the many brave, hardworking people who established the chairs and the research teams here. They were working in extremely adverse circumstances, with the aura of a “red university” hanging over them. It was very hard to overcome, but they succeeded,by taking steps such as our own Sztuka Górnego Śląska. It took a great deal of civic courage, not the spectacular sort, but the kind of “we try to carry on as usual”. We had fantastic support from the academic communities in Wrocław, Krakow and Warsaw. The world of the academic community was outside all the barriers and divisions of that time. And this is the source of immense academic benefits for us. Today, with access to the international community and without even the barrier of passports, we don’t know how good we have it.

Ł.G.: The cover of the book shows a detail of the neo-Gothic building of the Katowice Academy of Music alongside a fragment of its contemporary extension.

E.C.: We deliberately juxtaposed those two elements – the Prussian architecture of the Academy of Music building, formerly the Construction School in Katowice, much criticised neo-Gothic, scorned not only as a style, but above all as a symptom of “Prussianness”, and the modern shape of the Centre for Musical Science and Education, with its beautiful glazed surfaces. A glorious symbiosis which to me speaks louder than any amount of words.

Ł.G.: When the Polish voivodeship of Silesia was created between the wars, and its authorities announced a competition for a building for the Silesian voivodeship offices, the competition rules stated unequivocally that “the Gothic style will not be considered.” Now I look at the brick cuboid of the new concert hall, whose power of expression lies in its picturesque brick theme, and I think: “Gothic style welcome.”

E.C.: And no more “buy a brick” (laughs). This is where I see hope.

I am aware that we have the great luxury of being able to talk about all of this without the burden of unease or fear – it is a great gift not to be ordered to formulate our opinions and judgements in this way or that. It was this brand of freedom that we hoped to preserve as we worked on Sztuka Górnego Śląska. To be guided solely by the criteria of taste, knowledge and conscience. No-one commissioned this work from us; it was born out of our own inner need.

Taken up with our own minutely defined tasks, we are not constantly on the lookout for great purposes or goals, and it is only at moments such as this conversation that I realise how far we have come and how much good this has produced.

Copyright © Herito 2020