Conflicts of Memory

Upper Silesian Conflicts Concerning Historical Memory

Publication: 27 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESWould we dare to abandon set images, which have lost credibility, and – considering potential misjudgement – revise the ancient ideas and view ourselves from a distance, without all the heroics and with just a dash of humour?

What is history-rooted memory as the substance of our identity? We ask this question very often these days, trying to define ourselves and our origins. The issue, however, has turned out to be very complex, and it has generated many conflicts.

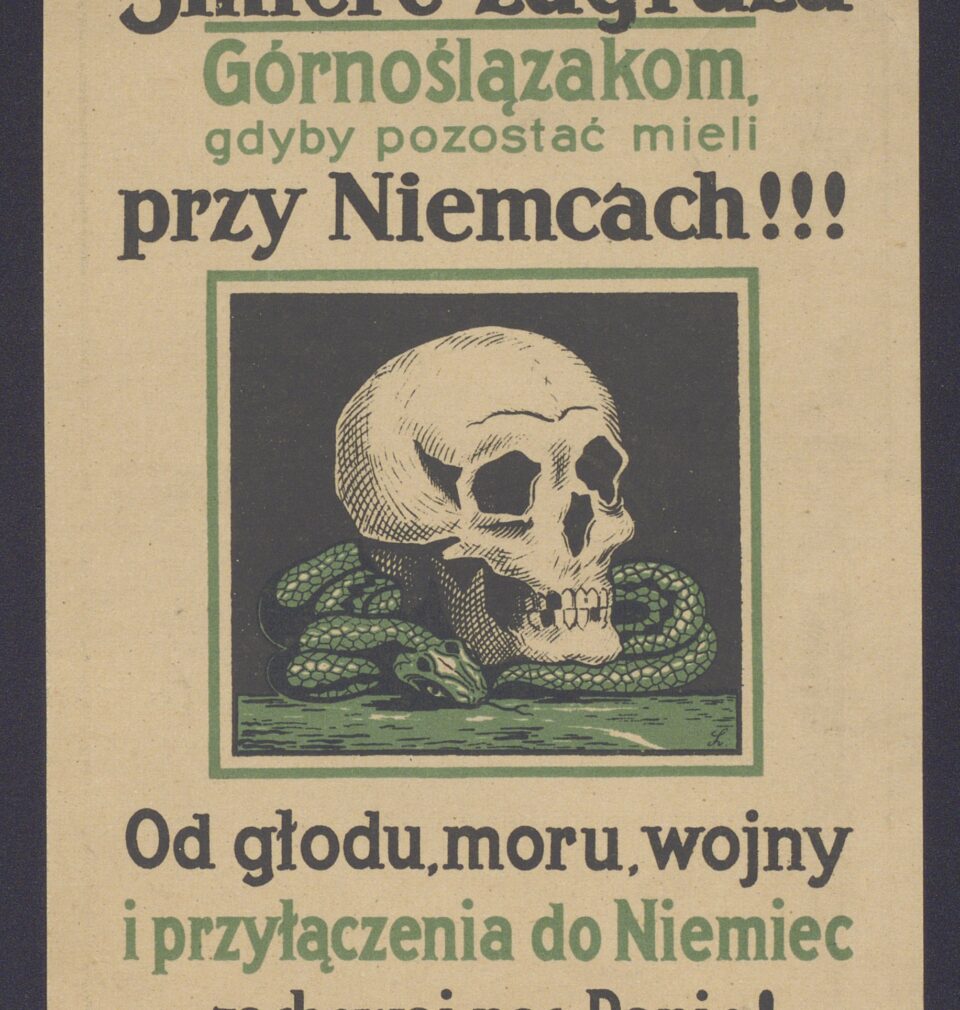

The problem has many threads, but we will focus on two of them. The first, more general one involves contemporary thinking in the process of abandoning the stereotypes of set homogeneity. The other concerns the drama which has occurred in Upper Silesia – a difficult region that has eluded the standards of both the People’s Republic of Poland and the Second Polish Republic – a region of many threads, in which, at some point, a giant industrial leap has occurred that has been recently experienced as post-industrial twilight.

However, let us begin with the first problem. We are increasingly asking ourselves the following: “Who am I?” and “What are our roots?” We are asking about our individual and collective identities. There are no present answers to these questions. Today, in the world of freedom – as we have been more or less inclined to see the period following 1989 as such – we need to define our identities on our own, in a responsible, painstaking manner. We need to define who we are in the most serious way that is neither glorifying nor condemnatory.

Our diversity manifests itself then – it turns out that some people invoke their borderland origin, whereas other see themselves as originally Silesian, Zaglembian, German, Jewish, Lesser Polish, Pomeranian, or Lemko. There are also the lives of their parents and grandparents – sometimes dramatically tangled and difficult to comprehend, as for a long time, we had been led to believe that these issues do not exist, or, worse still, they had been banned. Thus, they were discussed in secret, creating a bizarre “underworld” of divided consciousness. In fact, these problems have always been outlawed by totalitarian dictators, who claim the exclusive right to decide who we are and who we are supposed to be. Ideological doctrinarism forcibly unifies people within the given system, with regard to their race, class, religion and nationality. Individualism has been hijacked and harnessed by administrative and legal systems, through police surveillance, ugly denouncements (such as the one by Pavlik Morozov), as well as by producing fear and compliance in people.

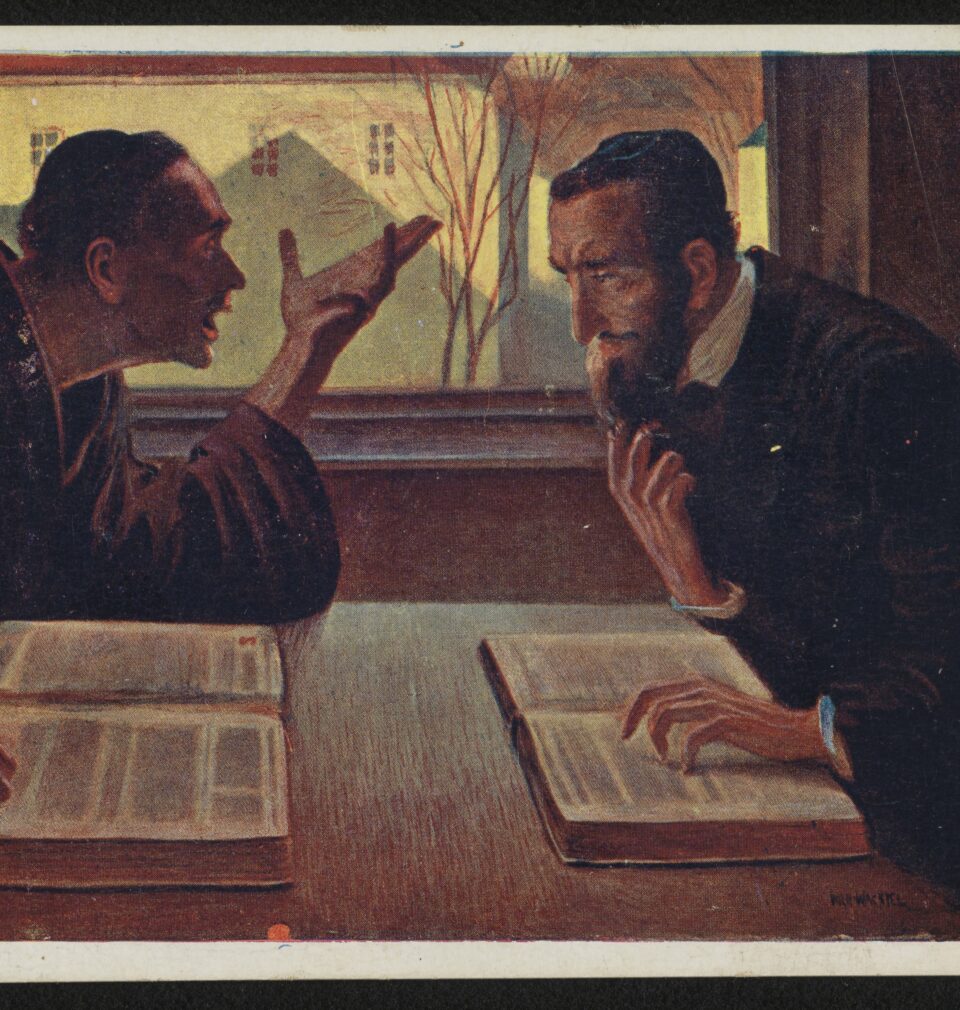

As we broke out of this vicious circle, we discovered new perspectives to human relationships over the last few decades, and we have broadened our definitions of personal, as well as familial, group, and regional identities, defying old restrictions. It is not an overnight process, most obviously. Our thinking has often been affected by age-old negative stereotypes of Germans, Jews, Ukrainians, to name but a few, by all sorts of pejorative connotations, which make us reject all outlanders. You just cannot be related to a rabbi or a Wehrmacht officer, can you?

Polish society of the post-Romantic age has often been ascribed an alarming characteristic, namely, it has lost the wonderful ability it boasted during the pre-partition period, in the Jagiellonian Era – the ability to attract, assimilate, and Polonise strangers in a hospitable, open, tolerant way. It has been sometimes replaced by rejection.

Meanwhile, when, against all odds, integration has occurred in Europe, which seeks to change its image and to re-define its ideological identity (which is more difficult to achieve than dealing with economic and technological issues, after all), the Upper Silesian borderland faces a task of defining its individual and collective identities, creating a new civic unity based on the complex matter of the region’s cultural diversity and historical inconsistencies. This matter generates conflict rather than bringing people together, especially considering the old dictators’ idea of perfect uniformity. Let us refer to an experienced expert on dealing with such kind of differences, namely, Paweł Machcewicz, director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, who has wrestled with the same problems as we have here in south Poland – and, as we know, has discussed them in detail in his numerous polemical publications[1]. He claims that “no one has a monopoly on deciding what Polish mentality is about. Polish people present many diverse ways of thinking and it is one of the greatest values of democracy we have enjoyed since 1989.”[2]

Nevertheless, the problem has become alarmingly complicated. We are searching for our roots in the most creative fashion, but at the same time we try to find our place in modern reality with very little support from large institutions, including the Church. What is more, it seems that we have only started digesting our experiences and the complex legacy of the 20th century, especially after 1945, with its epidemic of fear and hate engulfing the victims as well as the perpetrators. In this context, a heated dispute flared up recently, shaking the local Silesian community like a hurricane and causing quite a stir in Poland and abroad. It involved an exhibition devoted to the history of Upper Silesia, prepared in the newly built Silesian Museum complex – a project that was ended before it even began. Instead of presenting well thought-out arguments, looking to compromise, and showing the diversity and humour of the truly Brueghelian borderland landscape, a harmful request was expressed to the organisers that the exhibition should present a correct, Polonocentric image of the region, based on political control of collective memory and justified by the tradition of anti-German attitudes. The argument about Goethe and a steam engine from Tarnowskie Góry appeared to be ludicrous, and the head of the Museum, Leszek Jodliński had to resign.

The issue can be presented as above, namely, in an oversimplified way. However, it is more complex than it might seem. After all, ideologically based arguments have often occurred in European history and they can be called a conflict of two incompatible paradigms. We use the term coined by Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago 1962). Admittedly, his comments are connected with natural history, but – in a metaphorical sense – they also apply to the phenomena discussed here.

Science consists of constant development; paradigms (models, system) that have been created in order to describe and explain reality are conditioned by their time, they remain credible as long as they are not questioned by newly emerging systems. The most popular, once revolutionary, system was Copernican heliocentrism, which was replaced by new systems long ago and now belonging to the past. Based on this comparison, we can conclude that the unfortunate historical exhibition of Upper Silesia is a document of the present time: of the conflict of credibility between two incompatible paradigms – one of which involves national homogeneity and its primacy, a model originated in the traditions of education of the People’s Republic of Poland, promoting immutability, supported by the superior authority (akin to the old cuius regio eius religio, it seems). Then a new, dynamic approach emerges, one that is in blatant opposition to it and treats cultural tradition as a means of dispute settlement and acceptance of diverse forms of memory and historical narratives, especially those implicit in all borderland regions, including Upper Silesia. The new approach to presenting history aimed at illustrating the constant development. It involved a certain fear, namely, would we dare to abandon set images, which have lost credibility, and – considering potential misjudgement – revise the ancient ideas and view ourselves from a distance, without all the heroics and with just a dash of humour?

In this respect, Upper Silesia shows similarities with what could be called our own miniature Europeanism. The region is situated between original Poland and a land of “Nowhere”: the Western Lands, which remain culturally alienated. No national myth has ever originated in the Silesian borderland, which cannot be associated with the great Sarmatian and Romantic traditions – the poet felt connected with Bakhchysarai rather than Opole. Polish Romanticist manor houses have remained exotic to the resident of a familok, they deepen a feeling of otherness in him. He relates to the paintings of the Grupa Janowska art group, the imagery of young artists from the local Academy of Fine Arts, the poeticised coarseness of great industry, the post-industrial confusion, and the memory of 20th-century tragedies, still undigested and masked by stereotypes of correctness. A quote from Goethe’s Faust, “Who is not afraid to call things what they really are?” comes to mind.

Tragic memory emerges here, which is accusatory like a differently oriented Jedwabne: the memory of postwar camps such as in Świętochłowice-Zgoda, of thousands of people deported to the coal mines in Donbas, of the autochthons being degraded for their wrong accent and Silesian talk. This memory has been given voice to in the theatre, in Ingmar Villquist’s performance Miłość w Königshütte (Love in Königshütte), causing uproar.

Paradoxically, some researchers present a different approach to the problem: a difficult memory of the past is important in the research of Czech, Polish and German history, even in case of preparing a joint study on it, despite the fact that it may illustrate completely different views of the same issue[3]. Authors of literature devoted to the art of the region have done it in a similar manner[4].

Therefore, we need to bear in mind that historical memory as the substance of history is determined by different factors – winners and those who have the power will see history in a different way than losers, who oppose them as a rule. Researchers ought to weigh arguments sine ira et studio and to create a narrative referred to by Krzysztof Pomian as critical history[5], to the degree that the situation and their moral courage allow.

It is in the context of these experiences that a future presentation of the history of Upper Silesia should be developed in the form of a multimedia museum exhibition, as a narrative and a work of art. The Silesian Museum in Katowice is now faced with this task, which is very difficult considering the political dictate that blighted the project begun a year back. Will this situation affect the credibility of the present arrangements? How will the new variant deal with that tangled, difficult history? Time will tell.

The memory of Upper Silesia has many aspects and it requires thorough analysis, as well as much empathy and tolerance. For the time being, the region has found its niche in contemporary Europe, which aspires to unity regardless of national, religious, civilisational differences that hamper the process. In addition to this, over many centuries, Europe has appeared as perversely ambiguous, always prone to question itself, to upset the existing order, and extremely apt at producing new realities from what it has destroyed. It is through this constant action that Europe has created its new images. The same thing can be experienced here, in Upper Silesia, this slightly provincial and yet truly European part of Europe, which has laboriously built its new image from the shatters of local history. It has built this image in the place which naturally generates a lot of tension: we will understand it better if we look at the region as a whole in perspective – and we will see two historical and cultural “tectonic plates” of Europe, namely, agrarian and industrial cultures, touch, collide, overlap and blend.

This is just one, perhaps the most spectacular, example of the region’s complexity, which makes it so alluring. Due to such an understanding of history, it is tremendously difficult to create a credible picture – or indeed pictures, of this heritage.

Translated from the Polish by Paweł Łopatka

***

[1] Cf. Paweł Machcewicz, Spory o historię 2000–2011, Kraków 2012.

[2] Paweł Machcewicz’s statement concerning the programme of politicisation of museums included in Jarosław Kaczyński’s speech at a PiS (Law and Justice) convention in Sosnowiec; cf. Adam Leszczyński, “Kaczyński polonizuje muzea”, Gazeta Wyborcza, 152, 2 July 2013.

[3] Cf. Joachim Bahlke, Dan Gawrecki, Ryszard Kaczmarek, Historia Górnego Śląska. Polityka. Gospodarka i kultura europejskiego regionu, Gliwice 2011.

[4] Cf. Ewa Chojecka, Jerzy Gorzelik, Irma Kozina, Barbara Szypka-Gwiazda, Sztuka Górnego Śląska od średniowiecza do końca XX wieku, Katowice 2004, 2009.

[5] Cf. Krzysztof Pomian, Historia. Nauka wobec pamięci, Lublin 2006.

Copyright © Herito 2020