Silesias

Silesia has a multiplicity of faces. Besides the name, it is difficult to find a common denominator between Lower and Upper Silesia or Cieszyn and Opole Silesia. The multidimensionality of the region has not been determined only by its three formative cultures: Polish, German and Czech. Other important contributors have been two great Christian traditions, Catholic and Protestant, to this day engaged in an intense dialogue with each other.Also the tragedies of the 20th century made their mark on the region, turning Silesia into a land of exile for many, its domestication taking a long time. Heterogeneity of Silesia also results from the fact that the region remains divided between two countries: Poland and the Czech Republic; but the Olza no longer divides the region in two, as the bridges across the river in Cieszyn are now open.

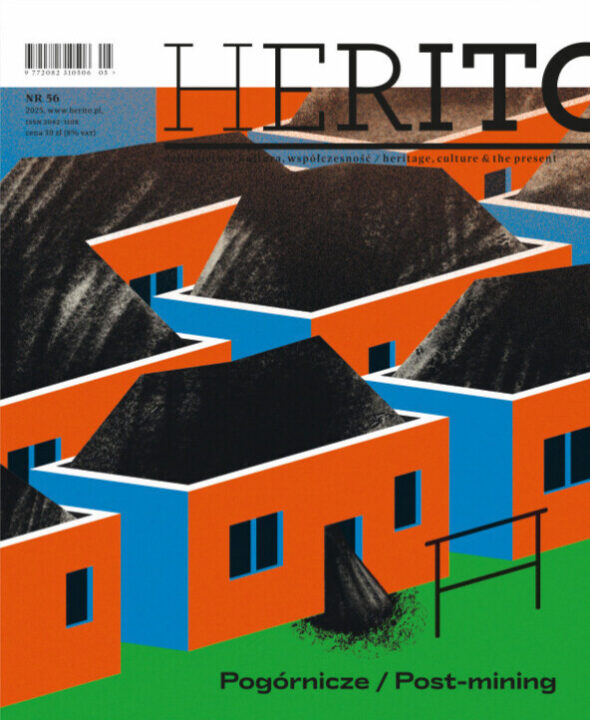

Because Silesia is mainly openness. Silesia owes its strong presence in the history of the European civilisation to this feature. Called the “emerald of Europe” in the 17th century, in the 19th‑century it became one of the main centres of the industrial revolution. The gene of modernity sprouted in this period and is growing fruit now – in Wrocław, which turned from an unwanted city into the European Capital of Culture 2016, or in Katowice, from a place of post‑industrial collapse becoming a UNESCO City of Music, joining the ranks of creative cities in Europe.

In this issue of Herito we speak about these metamorphoses and various facets of Silesia. And also about its otherness, owing to which Silesia is still not very well known, but this is where its greatest value lies.

Free full text articles

Copyright © Herito 2020