Stories From Countries Which Are no More

The Lost City of West Berlin. Landmarks of an Intermediary City Construct

Publication: 13 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLES“East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet”[1]

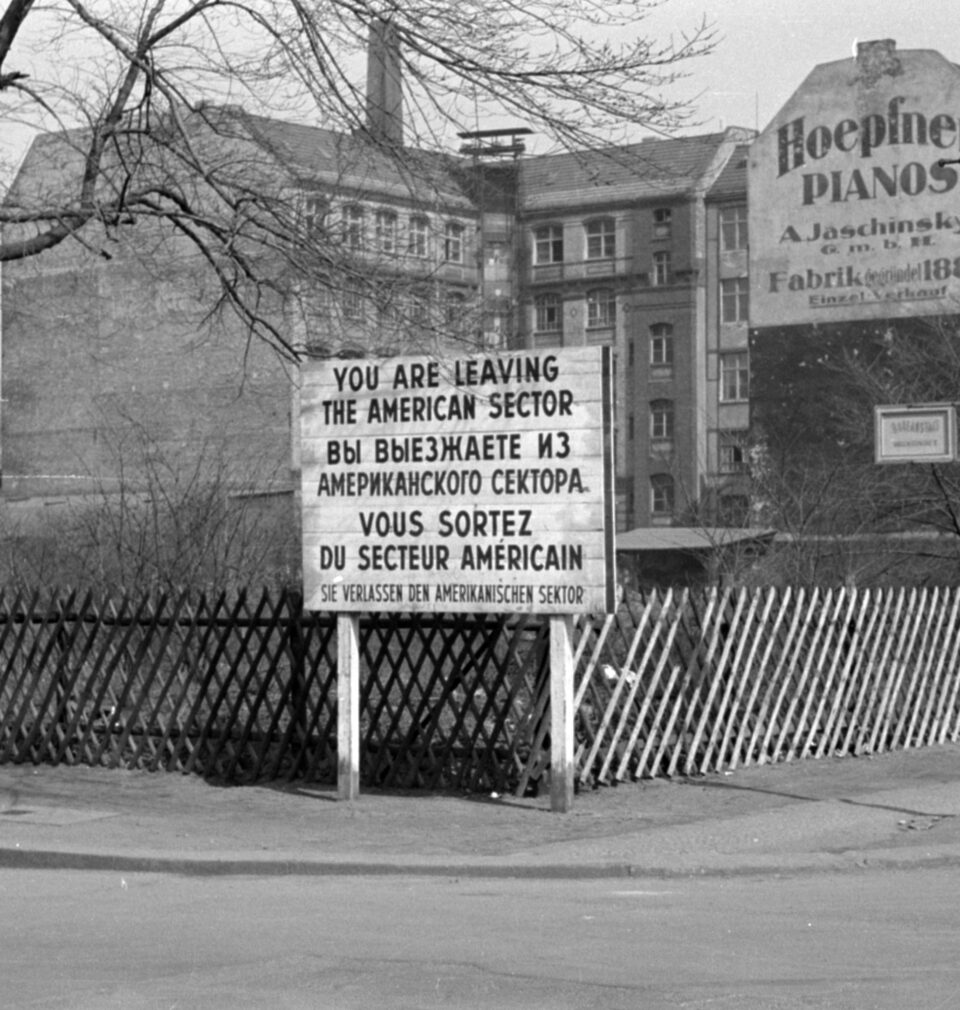

I was born in a lost city; a fragile city, a poor city, a half city, surrounded by a wall, but still open to fly away. A city without real citizenship, without any status, without real economy. A city occupied by three armies, in a hidden war with the troops in the other half of the city. Created as an artificial construct after a terrible war, which started in this capital, and vanished after a peaceful revolution: I was born in the city of West Berlin, and since 1990 I have been homeless.

More than 20 years after this revolution, Berlin is the capital of a new re-born Germany in the middle of a new Europe, but the wounds and rudiments of the lost city are still visible and sensitive. And although everybody knows that Soviet Union disappeared, and with it the German Democratic Republic (GDR), most people don’t realize, that in 1990, the Federal Republic of Germany (BRD) also disappeared, as well as West Berlin, a special artifact in between. Something new has grown up which is still looking for its position in Europe.

Today, you can still feel the broken history in Berlin, the different changes of meanings, the wounds of war, empty spaces, ruins of former great stations, street names without any meaning, cut connections, big buildings without any content. A city to explore an antagonistic network of history.

Berlin’s growth and decline

Berlin is a city with a fascinating history of growth and decline. Much younger than most other big cities in Europe, the small village of Berlin was founded in the 13th century as part of the German colonization of the East, although it had real importance for centuries, until the ruler of Brandenburg decided to reside in Berlin and to later become first king in Prussia and finally the King of Prussia. As a capital, Berlin grew quickly with the growth of Prussia, connected with the ideas of a modern state based on administration, the military and a tolerant culture. Berlin competed with Paris, London and Moscow, but never reached their status as a world city. And very late, in 1871, it became the capital of a late nation (and remained the capital of the state of Prussia in the German Reich). After 1871 Berlin had the chance to develop as a world city, and partly did, although autocratic regimes and two world wars not only destroyed the country, but also the importance of its capital. The Nazis started their cruel terror regime from the capital Berlin in 1933, but in fact they never liked this big and cultural open city, and they didn’t get the majority of Berliners’ votes in the last free election.

After the Second World War, Berlin lost its meaning completely. The city was located in the Soviet-occupied part of Germany and was divided into four zones, one for each of the Allies: the Soviet Union, the USA, Great Britain and France. This was founded on the “Four-Allies-Status”, which meant that the Allies had full power over the city together. After the foundation of the two German states in 1949, Berlin was divided into East and West Berlin, which was finally fixed through the building of the wall in 1961. However, the status of its occupation officially went on until 1990. Berlin lost its function as the capital of Germany – with the unknown Bonn becoming the capital of West Germany, and East-Berlin becoming the capital of East Germany (against the status). Berlin also lost its historical basis as the capital of Prussia, with the state of Prussia being finally dissolved by the Allies in 1947.

The construction of West Berlin

West Berlin was born in 1949 as an artificial construct of the Cold War system. The city was associated with the Federal Republic of Germany (Bundesrepublik Deutschland or the BRD), but was not really one of its states (Bundesland). The residents of West Berlin had the status of being associated members of the BRD, their passport were “provisional”, and they were not allowed to elect the parliament of the BRD – they could only elect the parliament of the city of West Berlin. The reason for this was that the occupation law still existed and the three Allies had the right to prove all laws and actions of the government of West Berlin. In fact the rights and duties of the residents of West Berlin were almost the same as in other states of the BRD, but the status of the city was different. The German army wasn’t allowed inside West Berlin, there was no military service, and the police were indirectly controlled by the Allies. The GDR had never recognised West Berlin as a state of the BRD, so West Berlin had somehow been an extraterritorial construction, occupied but almost free in its decisions, connected with the BRD but not legally part of it. A status of uncertainty.

Up until 1961, there was also the huge threat of the Soviet regime against the status of West Berlin – starting with the blockade of 1948 to 1949, and continuing with different crises and ultimatums – it was the only place were Soviet and US troops stood face to face, ready to shoot. Only the building of the wall “guaranteed” the status of West Berlin as an island, a prison with exits through border crossings and transit routes But as a result of these crises most of the big companies, cultural institutions and banks left West Berlin for other West German cities (and have stayed there until now). Thus, despite the political “stabilisation”, West Berlin had no economic background, and entrepreneurs wouldn’t invest in a city which only had transit routes. Half of the city’s households were subsidised by West Germany. Young people who wanted to have a career left, and those who remained were old people, students, and young people from West Germany who didn’t want to participate in military service, or who were looking for a place of alternative culture.

During the entire period between 1945 to 1990, West Berlin lost almost all of its importance, but as an occupied city divided into two (in reality in four) parts, its status demonstrated that the open question of post-war Europe and Germany still existed.

Urban concepts for a fragile city

This special situation created some special results in urban design and urban reception in West Berlin. In 1957 West Berlin staged the International Build-ing Exhibition at Hansaplatz: a manifest of modern architecture against the building demonstration of the GDR on Stalin-Allee with its neoclassical and “stalinistic” architecture. West Berlin realised the biggest areas of urban regeneration to demolish old workers neighbourhoods and to build special new social housing, demonstrating the “better” conditions of workers’ housing. The planning department planned to build a ten kilometre-network of highways, and to demolish most of its historical structure. More buildings were destroyed after the war than during the war.

The protest against the old-fashioned policy and against demolishing old neighbourhoods was also the strongest in West Berlin, with the 1968 protests and the civil initiatives in the 1970s – one of the melting pots for the foundation of the Green Party. In the early 1980s, the squatter movement finally stopped the policy of demolition and created a new West Berlin meth-od of urban regeneration: the “Careful Regeneration” (Behutsame Stadterneuerung) scheme of the Kreuzberg district. Together with social planning, participation and careful modernisation, it became a model of social-orientated regeneration for other cities.

Landmarks of a half city

The politicians of West Berlin also decided to create new architectural landmarks and to replace the lost cultural institutions which had been located behind the wall in the historical centre of East Berlin. Thus, they built the new opera “Deutsche Oper”, the International Congress Centre Berlin (ICC), the Free University and others. The architecture of these landmarks was designed in a modern, but cautious way, as after the bad experiences related to the meaning of representative and neoclassical architecture, the new face of West Berlin shouldn’t be dominant or excessive. After German reunification this created a special situation: Berlin is probably the only city in the world where all important state and cultural institutions exist in double, built in contrasting architectural styles, and having different psychological meanings.

At the same time, huge brownfield sites symbolised the lost meaning of the city: the former areas of the large dead-end stations, the big bunkers, the huge industrial sites, the empty harbours, and the areas of the former national government. Some of these areas are without function until now, while others have been converted into green areas, such as the railway tracks of Gleisdreieck.

A symbol of this special situation of loss of importance is the diplomatic quarter in Tiergarten-Sued, where all of the big embassies were concentrated until 1945. This included the new buildings of Germany’s new allies, Italy and Japan, designed in the “imperial” style of the end of the 1930s. All of them became vacant after 1945, with grass growing on their pretentious walls, and the destruction of war was never repaired. The embassies of the Baltic states were also situated in this district, which didn’t exist after the Soviet Union’s occupation – although the buildings were still maintained extraterritorially until the rebirth of these states in 1991. The former German parliament, the Reichstag, stood empty, without any function close to the wall. It took the genius of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who wrapped this lost building in aluminum covered fabric in 1995, symbolising the lost function of Berlin, transforming it into the new meaning of the democratic parliament of the new Germany in the early 1990s.

Urban life in an in-between city

The residents of West Berlin lived in a special situation during the 1970s and 1980s. They were able to experience the old signs of a strong capital of a large former “Reich”: the visible bunkers, the hidden tunnels, the ruins of the mega-projects of the Nazis; they could celebrate the dream of the golden era of the 1920s in some of the restaurants and areas that had been untouched; they took advantage of the open spaces and cheap housing – it was possible to buy a villa at Lake Wannsee for little less money, or to live in Bismark’s city apartment, not maintained, but big and nice; and they could walk around the old railway tracks without connections to the East, harbours without any logistic. In these fragmented spaces and unfinished history new initiatives and ideas could grow. It was possible to meet widows of old Nazis, poor women who had worked all their lives and lost everything, as well as former soldiers and peace fighters.

And if they wanted, the residents could participate and benefit from the presence of the American, French and British military, who were creating new links to the West. They could listen to the popular RIAS broadcasts (Broadcasting in the American Sector), or join the programmes of the British Council and the America Building to learn from the tolerant West. A melting pot of possibilities.

When the wall was torn down in 1989, it was very surprising and strange for the residents of West Berlin. Although they had suffered under this open prison, they had also organised themselves under this particular situation, with the isolation, with the broad opportunities they had under this cheesecloth. And they had to arrange their lives with the reality of the wall, next to which they had once walked, and painted their hopes. They showed the wall to visitors and climbed on the viewing platforms. But if a visitor cried about how unnatural and brutal the wall was, they didn’t understand these emotions and smiled back, feeling detached. Of course the residents of West Berlin were happy about the opening of the wall and celebrated it – but they also realised deep inside that their city, their special construction of life would disappear forever.

Urban concepts for the reunified city

After 1990 there was a huge expectation that Berlin would be reborn as a world city, like it had been during the 1920s. Large investments such as the one at Potsdamer Platz were started, a new main station was built, and huge development areas were made ready for building. But at the end of the 1990s it was realised that the number of residents was stagnating at around 3.4 million, most of the big companies and financial institutions were not moving to Berlin, the large areas were still empty, and that most of the residents were still poorer than they were in other German cities. Ten years on, brownfield sites still exist close to the new main station, and some of the huge housing projects like “Water City” Spandau still haven’t been finished.

At the end of the 1990s the Planwerk Innenstadt, an urban design concept for the inner city of East and West Berlin, was developed as an important step in understanding Berlin as a common city. It was focused on inner city development, building new town houses, and repairing the old city structure. In particular, the medieval city centre was to be thought about and designed with reduced traffic and reconstructed block edges. This Planwerk was the beginning of a long debate about the urban identity of the city., Which historical background should be the model for reconstruction: the medieval part, the 19th century part, the socialist part? Should it be “allowed” for this lost Berlin to reconstruct symbols of the lost German Reich? Discussions about the reconstruction of the old castle of Berlin in the medieval centre were especially controversial. For the understanding of the urban design of the old axis of Unter den Linden, the proportion of the castle was very important. But in the end the German government decided to rebuild it with the old façade, but without the old meaning – it could be interpreted as a sign that the new Germany didn’t feel ready to realise a new urban form instead of the rebuilding the castle.

Berlin has not become a new world city like Paris or New York, and it has not become the only centre between East and West. But it has become the centre of the government. The new government buildings were built in a modern but simple way in an East-West axis; not excessive, but also not cautious. Berlin has also become a centre for culture and tourism; it has become more and more international. And it had become a city which deals with responsibility and care with its bad past: there are a lot of monuments and museums dedicated to German history and especially about the war and the fate of the Jewish population. The new Holocaust Memorial and the Jewish Museum have been built as impressive signs of this in the centre of Berlin.

Berlin has become beware that the former networks to the East, as well as new partners like Poland and other countries, could be a starting point for new possibilities in the new European Union. It has taken a long time for the former elite of West Berlin to understand that since reunification, Berlin is no longer a “Western” city, but that it is more and more becoming an “Eastern” city, perhaps a city of the growing Middle Europe, with a new peaceful exchange of culture, economics and understanding; so that in the end, East and West could meet in this special place to overcome a century of division. The special construction of the extraterritorial unit of “West Berlin”, however, has vanished forever, and later generations will wonder what this ghost city was really like.

References:

Berliner Festspiele, Berlin: offene Stadt. Die Erneuerung seit 1989, Berlin 1999.

Harald Bodenschatz, Platz frei für das Neue Berlin! Geschichte der Stadterneuerung seit 1871, Berlin 1987.

Agnes Kohlmeyer, Felix Zwoch (ed), Idee, Prozeß, Ergebnis. Die Reparatur und Rekonstruktion der Stadt, Berlin 1987.

Detlef Kurth, Strategien der präventiven Stadterneuerung. Weiterentwicklung von Strategien der Sanierung, des Stadtumbaus und der Sozialen Stadt zu einem Konzept der Stadtpflege für Berlin, Dortmund 2004.

David Clay Large, Berlin, New York 2000.

Olaf Leitner, West-Berlin. Westberlin. Berlin (West). Die Kultur – die Szene – die Politik, Berlin 2002.

Planwerk Innenstadt Berlin, Berlin 1999.

Wolf Jobst Siedler, Phoenix im Sand. Glanz und Elend der Hauptstadt, Berlin 1998.

Gerwin Zohlen, Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Stadt. Berliner Architektur am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts, Berlin 2002.

***

[1] Rudyard Kipling, The Ballad of East and West, in: Edmund Clarence Stedman (Hrsg.), A Victorian Anthology, 1837–1895, Cambridge 1895.

Copyright © Herito 2020