Europe and the East. Decade of the Eastern Partnership

The Bauhaus as a Crucible of Central European Internationalism

Publication: 31 March 2023

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESThe month of April 2019 marks a notable centennial for the arts, architecture, and design. Exactly 100 years earlier, the thirty-five-year-old architect Walter Gropius founded Weimar Germany’s Bauhaus school, or State Bauhaus in Weimar (Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar).

The centennial will doubtlessly trigger numerous revaluations of Germany’s most influential twentieth-century arts school, as the 90th anniversary in 2009 saw the publication of nearly a dozen books, conferences, and exhibitions on the subject.[1] In this spirit, this article reconsiders the influence that artists and architects from Central and Eastern Europe had on the Bauhaus and its turbulent history during its short, fourteen-year life span, from 1919 to 1933.

The disproportionately large influence of the Bauhaus in helping to define twentieth-century architecture and design culture belied the school’s relatively small size. Given the enrolment of 231 students in the school’s first full semester in the autumn of 1919, few would have predicted that the Bauhaus would shortly come to tower over all other Weimar-era art schools in its long-range influence and notoriety. The source of the Bauhaus’s notoriety? An unabashed openness on the part of Walter Gropius, the school’s founding director: openness to the widest variety of new and experimental artistic practices, and, likewise, openness to drawing upon the talents of faculty and students from different countries and backgrounds, based solely on the criteria of artistic ability and motivation.

This openness was closely tied to the school’s reputation for promoting a progressive, outward-looking agenda – and was also responsible for the school’s near undoing. From virtually its first week of operation, the Bauhaus faced challenges over its international orientation. Objections to the school came from various quarters within Germany. For example, artistic “traditionalists” rejected the school’s embrace of Cubism, Expressionism, and abstraction, instead favouring historical painting and sculpture along national, classical, or romantic lines. Right-wing Volkish populists likewise objected that the Bauhaus’s cosmopolitan internationalism undermined “German” values and stability. Populists were joined by outright xenophobes who, in their hatred for the international flavour of much modern art and culture, denounced the Bauhaus’s very existence, threatened its shutdown, and forced actual closures and relocations of the school once they managed to achieve right-wing political majorities. This occurred, for instance, in 1924, when victorious right-wing political parties forced the closure of the Bauhaus in Weimar; the school reopened in Dessau under the sponsorship of a sympathetic mayor, Fritz Hesse, who helped the school forge productive links to local industry. A similar dynamic was repeated in 1930, resulting in the closure of the Dessau Bauhaus, only to see the school reopen in Berlin. The Bauhaus closed for a final time after the Nazi accession to power in 1933.

And here is the point of this distinctly political focus on a path-breaking interwar art school: German national identity in the Weimar era, following the shattering defeat of the First World War, was bound up in equal measure with national rebirth, on the one hand, and a new national architectural and artistic self-definition on the other. Inasmuch as the nations of Central and Eastern Europe were also forging national identities after the war – some for the first time ever in the modern era – artists and architects also entered into the debate. Often this found expression through political participation in such revolutionary groups as the socialist “Workers’ Council for Art,” the Expressionist “Glass Chain,” or other groups. Equally important, artists’ creative output frequently came to be associated with political expression and affiliation. Germans were by no means alone in debating such national questions as: were artistic immigrants to Germany a boon for social organisation and national creativity, or did they pose a threat to the artistic and ethnic integrity of the German population? The political implications of artistic production preoccupied the re-formed and newly formed nations of Central and Eastern Europe, enlarging in significance during times of heightening tensions over nationalself-definition.

Yet during the Weimar era, Gropius was remarkably unflinching in his dedication to hiring the very best artistic talent available, regardless of country or culture of origin. Yes, late twentieth-century scholars have uncovered unbuilt architectural competition submissions by Gropius and a later Bauhaus director, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, for ministries that Nazis wished to construct in the 1930s; ideologically, however, Gropius seems to have remained committed first and foremost to an international community of talent, and not to any particular ethnically defined national group.[2]

Lyonel Feininger, the very first Bauhaus faculty member that Gropius hired, came from the United States; Feininger was born and raised in New York City to German Jewish émigré parents, and would teach oil painting and remain associated with the Bauhaus for all fourteen years of its existence. Additional faculty that joined the school soon after included the Russian avant-garde painter Wassili Kandinsky and the Swiss painters Johannes Itten and Paul Klee. Gropius found it necessary to replace Itten in 1923 after a productive but controversial four-year tenure. For his replacement Gropius tapped the Hungarian artist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, whose energy, experimental spirit, and charisma would galvanise the school, and lead him to open the New Bauhaus in Chicago after World War II. Other Hungarians who had an impact on the school included Marcel Breuer and Farkas Molnar. Molnar’s legacy as a committed modernist would be felt after he returned to his native Hungary, while Breuer would rise from being a student “apprentice” to join the faculty of Bauhaus “masters,” as the school’s instructors were called. Breuer’s influence as an internationally acclaimed architect would increase exponentially when he joined Gropius during the latter’s tenure as chair of architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in the late 1930s.

The international scope of the Bauhaus faculty and student body unquestionably contributed to the school’s success as a beacon for the avant-garde. Nations like Romania, for example, would produce an avant-garde consisting of architects like Marcel Janco, Duiliu Marcu, and Octav Dolcescu. None of these men attended the Bauhaus, but their best-known buildings consciously drew upon local elements while emphasising modernist abstraction and adopting industrial materials like concrete, steel, and glass, all favoured by Gropius, the Bauhaus, and the influential Paris-based Swiss architect Le Corbusier. Romanian progressive architects’ participation in what would come to be known as the “international style” reflected the degree to which beacons of modernism in Western Europe shone the way for newer nations in Central and Eastern Europe to promote themselves, and especially their capital cities, as modern and forward-thinking.[3]

A second contributing factor to the Bauhaus’s reach and reputation was the undisguised idealism of its curriculum, along with its dedication to the role of the arts and architecture in rebuilding a dispirited and defeated German society after the First World War. In a four-page Bauhaus curriculum and mission statement, Gropius idealised the medieval German past, a time when builders’ lodges and artisans’ guilds collaborated with artists, sculptors, and architects to erect such communal structures as the Gothic cathedral. Even the name “Bauhaus” was seemingly chosen to fortify the modern school’s mythical ties to medieval lodges by evoking the ancient German word “Bauhütte,” a medieval guild of craftsmen and building-trades workers.

Extolling craft as the “ancient source” of all artistic activity, the Bauhaus Program promoted egalitarian unity in the collaborative process of forging new, collective works of art and architecture[4]. With the crafts as their unifying base, the arts would experience a revival analogous to the post-war social democratic ideal of workers reviving Weimar German society from below. As Gropius observed in his essay for the “German Revolutionary Almanac”, “new, intellectually undeveloped levels of our people are rising from the depths. They are our chief hope.”[5] Like Berlin Dada, Dutch Neoplasticism, or the experiments of Constructivist art schools in Moscow, the Weimar-era Workers’ Council for Art and the early Bauhaus tended to regard the upper-class and bourgeois worlds with suspicion; in their push for industrial concentration, military expansion, and capitalist development, leading members of these classes were understood to have propelled Germany into the disastrous First World War. The working classes, represented at least symbolically at the Bauhaus by craftsmen and, over time, by industrial designers, offered inspiration for the development of a socially relevant new art. This art would in turn support a new and authentic social order, one that required new aesthetic principles as well as novel forms.

Students from Germany, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, Poland, the Baltic states, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria therefore began their studies at the Bauhaus by taking a bracing, six-month introductory course (Vorkurs) designed to unburden them of art’s historical baggage and unleash individual creative potential. The next level of study involved mastering an individual craft of their choice, with the aid of practical instructional workshops in woodworking, ceramics, book binding, weaving, metalworking, and sculpture. Only upon successful completion of this stage, lasting from one to three years, would students be allowed to contribute toward the “ultimate” artistic goal, the fully realised building, which stood like a bull’s eye at the centre of the Bauhaus curriculum diagram (Figure 1).

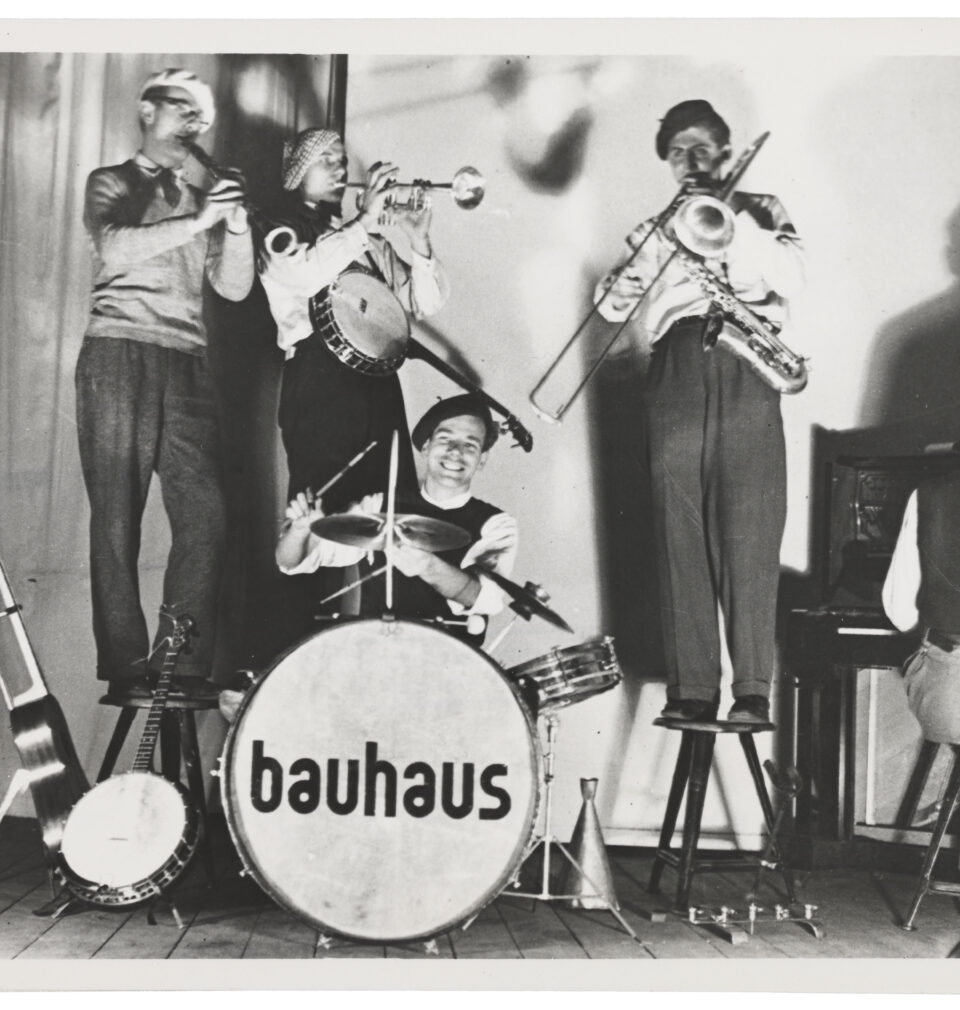

As Gropius explained in his 1923 publication “Theory and Organisation of the Bauhaus,” the aim was “a center for experimentation which will try to assemble the achievements of economic, technical and formal research and to apply them to problems of domestic architecture in an effort to combine the greatest possible standardisation with the greatest possible variation of form.””.[6] When the faculty expanded in the early 1920s, leading artists like Klee, Kandinsky, and Oskar Schlemmer taught courses in painting, art theory, typography, and set design, while over time the school collectively explored a variety of performance-based media, including music and experimental theatre. Architecture, considered by Gropius to be the “mother of all the arts” after the British art critic John Ruskin’s dictum half a century earlier, did not become an official Bauhaus department until the school relocated with new energy and funding in Dessau in 1927.

Rather than representing any particular philosophy, style, or precisely defined approach to design, the Bauhaus was always “an idea,” in the famous characterisation from the school’s third and final director, the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The school was always the idealistic, collective product of its influential faculty and individualistic students, whose experimental inclinations were brought into focus by the school’s three successive directors. Thus Gropius, the director from 1919 to 1928, presided over the Bauhaus’s initial (and, thanks to hostile conservatives in the legislature, chronically underfunded) crafts and Expressionist phases in the early 1920s. By 1923, he adopted a fresh, Constructivist-influenced school slogan, “Art and Technology: A New Unity,” which became the title of the Bauhaus’s first major design exhibition in the summer of 1923. The Swiss architect Hannes Meyer assumed the directorship between the years 1928 and 1930 and reoriented the school to a scientific Marxist program of simple, affordable, practical furnishings and architecture. Mies van der Rohe, in turn, realised his “idea” for the school as director between 1930 and the school’s closure in 1933; he abandoned Meyer’s Marxism and focused students instead on the systematic and rigorous practice of architecture. This rich trajectory offered many opportunities for artists and architects throughout Central Europe to be inspired by various aspects of this leading Weimar German school’s development.

A synthesis of the crafts, fine arts, and architecture quickly emerged as Walter Gropius’s modern Bauhaus ideal. Of course, early antecedents for this principle could be found as far back as the ancient Greek Parthenon and, as the Bauhaus Program noted, in the medieval cathedral. But in the post-war desire for collective German and Central European national rebirth, it became easier to imbue ancient notions with fresh significance and renewed possibility.

Gropius’s Bauhaus Program exuded confidence in modernity’s endless capacity for renewal. “The ultimate goal of all artistic activity,” the program declared, “is the building. To decorate it was once the noblest task of the visual arts, they were indissoluble components of the great art of building.”[7] Adapting architect Otto Bartning’s revival of the nomenclature of medieval society, the Bauhaus Program replaced such academic titles as “student” and “professor” with the medieval “apprentice,” “journeyman,” and “master.” These idealistic designations set the school apart from the art academies and applied arts schools of recent decades. Gropius concluded the Bauhaus mission statement on a high note, proclaiming: “Let us collectively desire, conceive, and create the new building of the future, which will be everything in one structure: architecture and sculpture and painting, which, out of the millions of hands of crafts workers, will one day rise towards heaven like the crystal symbol of the new and coming faith.”[8]

Gropius’s rich imagery invoked at once the medieval, communally constructed German cathedral and a “new faith” in the architecture of Expressionists like Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig, and Erich Mendelsohn. As its earliest promotional document, the multivalent Bauhaus Program further connected the crafts “base” of medieval society to the new social order, a social democratic majority analogous to “the millions of hands of crafts workers,” whose constructions would rise toward heaven. The Bauhaus Program gained international attention, and has to be given credit as a major document responsible for attracting idealistic young students and faculty – or “apprentices” and “masters” – from across German-speaking Central and Eastern Europe. Gropius wanted to create more than just a modern art school; he wished for the Bauhaus to be both a mirror and a model for the emerging Weimar German modern social order.

Gropius invited Lyonel Feininger to design a visually compelling cover for the Bauhaus Program. Feininger rendered the “crystal symbol of the new and coming faith” in the form of a dramatic Cubist-Expressionist woodcut, entitled “Cathedral” (Figure 2). Like other Expressionists before him, Feininger consciously employed an artistic medium developed in the Middle Ages, the wood-cut, to infuse his modern imagery with a kind of primitivist power. His “Cathedral” presents the front elevation of a building comprising three gabled portals, three levels of flying buttresses, and three towers, all topped by three stars emitting bright rays of light. This vertically organised set of triads is highly suggestive of the Holy Trinity, a cornerstone of Christian doctrine frequently symbolised in the interior “triforium” and clover-leaf “trefoil” ornaments of actual medieval cathedrals. At the same time, the triangle of stars radiating light above the building seems to suggest the applied and fine arts organised under the leadership of architecture, here given a notably cosmological significance.

However, like the Bauhaus school itself, Feininger’s jagged, Cubist-Expressionist lines and pulsating emanations of light, structure, and shadow expressed an aesthetic that could easily offend conservative artists wedded to older academic traditions. Amid the divisive politics of post-war Germany, many conservatives saw avant-garde art not as the dawning of a promising new age, but as fundamentally threatening to an established social order. Precisely that which inspired youthful Central European avant-garde seekers of new aesthetic truths, in other words, was prone to offend those who remained suspicious of experimentation in virtually all its forms. Appealing to Germans’ sense of their culture’s historical achievements in the Middle Ages, and deftly skipping over any debts the school owed to Wilhelmine precedents, the Bauhaus became a veritable poster child for social democratic efforts to rebuild a war-torn country and refashion German society. The question was whether the school could present new aesthetic forms in the crafts, fine arts, and architecture in ways that Germans of all political persuasions could embrace.

For its initial phase in 1919-1920, the Bauhaus represented a parable of a harmonious German society in which practitioners of the crafts, fine arts, and architecture cooperated in a purer, less mediated form of artistic production. Yet promises of communal harmony proved elusive. If the founding of the progressive Weimar Bauhaus aroused the ire of the town’s cultural conservatives, the school also suffered early attacks from a less expected quarter: its own student body. During the first full semester of instruction in the fall of 1919, thirteen students – or some five percent of a total student body of 231 – resigned en masse in protest over the Bauhaus Program and its curricular innovations. The Bauhaus masters’ executive committee meeting minutes (unavailable to Western scholars until the end of the Cold War) help to reconstruct the students’ actions and motivations. According to meeting minutes from 18 and 20 December 1919, Walter Gropius and the director of the Weimar School of Building Trades, Paul Klopfer, attended a special assembly called by Weimar’s Free Association for City Affairs (Freie Vereinigung für städtische Interessen) to discuss the Bauhaus and “the new art in Weimar” on 12 December. There, the minutes record, the chair of the meeting, Dr. Emil Kreubel, levelled attacks against the Bauhaus that Gropius and Klopfer “successfully parried.” The architectural historian Barbara Miller Lane recounts Kreubel’s comparison of Cubist and Expressionist painting to the artistic output of patients at a mental hospital. As Kreubel denounced the school for being a “Spartacist-Bolshevist institution,” individual agitators in the audience added catcalls of “Jewish art” and “foreigners.”[9]

A Bauhaus student named Hans Gross then rose and “Unfortunately made a speech to the gathering against the trends embodied by the State Bauhaus. This was all the more surprising,” the minutes continue, “because Gropius had coincidentally encountered Gross on the afternoon of the special assembly, and Gross had explained that he thoroughly approved of the goals of the State Bauhaus and was prepared to follow Gropius through thick and thin.”[10] Ensuing executive committee discussions make clear that among Bauhaus students, Gross had initiated the “circulation of an anti-Semitic petition on which his own name failed to appear.” He also delivered a “German nationalist party speech which, prepared in longhand, was read at a public gathering of students on Friday, 11 of December.””.[11] What emerges from heated executive committee discussions is that Gross denounced both the foreign and Jewish representation at the Bauhaus as “un-German,” a tactic common enough among the xenophobic far-right. Here, Gross joined those right-wing Germans who consoled themselves for Germany’s defeat by accusing German Jews and left-wing “traitors” at home of having undermined the war effort. The so-called “Dolchstosslegende” held that Jews and the left had “stabbed Germany in the back,” thereby causing the German Empire to lose the war. In his speech at the meeting, Gross further claimed that Bauhaus assignments in the autumn 1919 semester, which focused on the making of toys and other three-dimensional objects, were preparation for a ban on the venerated artistic tradition of easel painting. Gross’s public assault and resignation from the school with a dozen other students made clear how closely arguments about modern art and cultural production were tied to political definitions of German identity and notions of both the aesthetic and the political future.

The masters’ executive committee submitted an immediate, detailed written rebuttal – a carefully worded blend of defence and offense – to the Weimar Culture Ministry officials overseeing the school. The document refuted Gross’s specious assertions and included an exact breakdown of the 231 students enrolled at the Bauhaus in 1919 by nation of origin: 210 Germans, fourteen Austrian Germans, two Bohemian Germans, three Baltic Germans, and two Hungarian Germans. The two elected student representatives were not foreigners, as Gross maintained, but were in fact Germans of Austrian extraction. The only traitorous and “un-German” behaviour at the Bauhaus, the masters’ rebuttal emphasised, was that of the student Hans Gross himself. Gross trafficked in deliberate untruths and denunciations, and he had disgraced both the school and other Bauhaus students who were “especially qualified, including some who participated in the war and achieved officers’ rank.”[12]

The Bauhaus painters Lyonel Feininger and Johannes Itten thereafter signed a public statement affirming that they had every intention of continuing to practise and teach the art of easel painting in their studios and classrooms. A second statement, signed by all members of the Bauhaus masters’ executive committee, forbade student participation in political activity “regardless of which side” or ideological persuasion, “on penalty of expulsion.”[13] Seeking to dampen sustained criticism in the local and national press, Gropius withdrew from the progressive artists’ groups, the Workers’ Council for Art and the November Group, after overseeing the former merge with the latter on 17 December 1919 in the midst of the Bauhaus controversy. Gropius thereafter maintained a safe distance from left-wing organisations and would, in fact, insist at every opportunity that the Bauhaus was “unpolitical.”

Not a single one of his enemies listened. Despite Gropius’s increasing propensity to argue in the 1920s that art should be regarded as occupying a realm separate from politics, and notwithstanding the resolute avoidance of any official political involvement by himself or his school, the Bauhaus remained a target for the right. For his part, Gropius promoted the school tirelessly in a blizzard of press articles. The frequency of his public lectures moved the architectural historian Winfried Nerdinger to characterise Gropius as a “wandering preacher of the modern.”[14]

Throughout his years as Bauhaus director, Gropius stood by his conviction that artistic vision and talent were of paramount importance in post-war Germany’s cultural rebirth, regardless of a person’s background or nationality. In the months after the Bauhaus controversy, he resisted calls from Weimar conservatives and chauvinists to hire more Germans and follow German academic traditions more closely. It was unclear, after all, what could precisely be called “German” about the nation’s academic art traditions; for centuries, Germany’s artistic education derived from practices in France, Holland, or Italy, and before that, Greece. Gropius continued to hire and defend leading artists from the European avant-garde: the Swiss painter Johannes Itten, originator of the famous six-month, pass-fail Bauhaus “Introductory Course” on elementary form and materials; a second avant-garde Swiss painter, Paul Klee, member of the pre-war, early Expressionist “Blue Rider” group; the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of painterly abstraction and synaesthesia, and co-founder of the “Blue Rider” group in Munich; and the Hungarian painter László Moholy-Nagy, an experimental media artist. Gropius hardly wrapped himself in the German flag in making hiring decisions. The artists he recruited reflect the Bauhaus director’s unerring eye for the best German and international talent, a group of Bauhaus masters that are celebrated to this day as leading innovators of twentieth-century art.

Keeping abreast of prevailing theories in international architectural and design, Gropius corresponded with leading architects such as Le Corbusier in France and took valuable cues from the Russian Constructivist and Dutch de Stijl movements. Each in their own way, Constructivism and de Stijl sought a rapprochement between art and industry in the name of social progress. Following an international Constructivist conference in Dusseldorf in 1922, Gropius was determined to set the Bauhaus on a new course. Against the strenuous objections of the most popular Bauhaus teacher, the charismatic and mystical Johannes Itten, he introduced a Constructivist-style slogan, “Art and Technology: A New Unity,” for the Bauhaus’s first major exhibition in summer 1923.

Itten, after a prolonged struggle with Gropius, resigned from the school in disgust. His departure greatly disappointed a devoted group of students who, in close emulation of the example set by their favourite Bauhaus master, had shaved their heads, donned monks’ robes, adopted yoga and deep-breathing exercises, and practised vegetarianism. Itten’s replacement, the Constructivist László Moholy-Nagy, was the perfect choice to signal the school’s new direction, skilfully guiding students through the Bauhaus Introductory Course, supervising the school’s metal workshop, and pioneering experiments in a variety of new media.

Quite apart from any troubled internal politics at the school, the unprecedented inflation of 1923-1924 rocked the worlds of Weimar and Thuringia. Right-wing parties displaced a Thuringian coalition of socialists and communists in 1924, overshadowing celebrations that followed the first major Bauhaus exhibition in the summer 1923. The victorious political right revived its old charges that the Bauhaus was a centre of “cultural Bolshevism” and guilty of crimes against the “German” traditions of Weimar classical architecture and the literature of Goethe and Schiller. With a clear legislative majority, the right-wing parties closed the Weimar Bauhaus in 1924.[15]

Before the consolidation of “strong man” politicians like Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini in the 1930s, wide-ranging experimentation in architecture seemed to be the order of the day. Czech national pride would help make movements like Czech Cubism prominent in the Bohemian capital, while Baltic nations like Lithuania, whose independence leaders had been inspired by the Czechs, designed a variety of modernist buildings for their interwar capital, Kaunas.[16] The flow of artistic ideas across international borders continued, facilitated by the activities and internationalism of schools like the Bauhaus, making the interwar era one of the most productive and experimental periods in the entire history of modern architecture.

This chapter draws upon two of the author’s earlier publications, “The Politics of Art and Architecture at the Bauhaus,” in Peter E. Gordon and John P. McCormick, eds., “Weimar Thought: A Contested Legacy”, Princeton, 2013, 291-315; and “Before the Bauhaus: Architecture, Politics, and the German State”, 1890-1920, Cambridge, 2005.

[1] The year 2009 saw publication of nearly a dozen international scholarly books, conferences, and exhibitions on the Bauhaus’s individual artists and their collective achievements in cities like Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Frankfurt, New York, and Chicago, as architectural scholar Martin Filler noted in a review essay 2010 essay commemorating the ninetieth anniversary of the Bauhaus’s founding. See Martin Filler, “The Powerhouse of the New”, New York Review of Books, June 24, 2010, p. 1.

[2] Winfried Nerdinger, “Bauhaus Architecture in the Third Reich” [in:] Kathleen James-Chakraborty, ed., Bauhaus Culture, Minneapolis, 2006, pp. 139-52; this is James-Chakraborty’s translation of Nerdinger’s original 1993 German essay, “Bauhaus-Architekten im ‘Dritten Reich,’” [in:] Winfried Nerdinger, ed., Bauhaus-Moderne im Nationalsozialismus: Zwischen Anbiederung und Verfolgung, Munich, 1993).

[3] The architectural scholars Luminiţa Machedon and Ernie Scoffham best make this point when they note: “Romanian architects did not form groups distinguished by their concepts of building, such as the Bauhaus, De Stijl, and other schools of avant-garde thought…Nevertheless, while pursuing their own individual ideas, all the architects expressed their attitudes to the formal and functional directions of the new architecture …and were united insofar as each conveyed the message of the international Modern Movement.” Quoted in Machedon and Scoffham, Romanian Modernism: The Artchitecture of Bucharest, 1920-1940, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, 1999, p. 66.

[4] See Walter Gropius, “Program of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” (April 1919), reproduced in Hans M. Wingler, The Bauhaus, pp. 31-33. View the original artifact on the web at http://arthistory.about.com/od/from_exhibitions/ig/bauhaus _1919_1933/ bauhaus_moma_09_01.htm (accessed August 1, 2018).

[5] Walter Gropius quoted in John Willett, Art and Politics in the Weimar Period: The New Sobriety, 1917-1933, New York, 1978, p. 50.

[6] Walter Gropius, “Idee und Aufbau des Staatlichen Bauhauses Weimar” [in:] Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar, 1919-1923, ed. by Walter Gropius, Weimar and Munich, 1923, pp. 7-18; quotation here from the translation, “The Theory and Organization of the Bauhaus” [in:] Bauhaus 1919-1928, ed. by Herbert Bayer, Walter Gropius, and Ise Gropius, New York, 1938, pp. 20-29; quotation p. 28.

[7] Walter Gropius, “Program of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” here quoted from the translation by Charles W. Haxthausen in Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman, eds., Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity, exhibition catalog, New York, 2009, p. 64.

[8] Walter Gropius, “Program of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” quoting from the translation by Charles W. Haxthausen in ibid., p. 64. The present author has made one minor adjustment to Haxthausen’s translation of aus Millionen Händen der Handwerker, which Haxthausen renders as “from the million hands of craftsmen.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Sitzungen des Meisterrates am 18. Dezember 1919 and 20. Dezember 1919, Meisterratsprotokollen, pp. 56-62.

[11] Meeting of 18. December 1919, Meisterratsprotokollen, p. 57.

[12] Meeting of 20. December 1919, [in:] Meisterratsprotokollen, p. 61.

[13] Meeting of 18. December 1919, in Meisterratsprotokollen, pp. 58-9.

[14] Quoted in Winfried Nerdinger, “Walter Gropius’ Beitrag zur Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts,” [in:] Peter Hahn and Hans M. Wingler, eds., 100 Jahre Walter Gropius: Schliessung des Bauhauses 1933, Berlin, 1983, pp. 17-36, quotation from p. 18.

[15] See Miller Lane, Architecture and Politics in Germany, pp.76-86.

[16] See Miller Lane, Architecture and Politics in Germany, pp.76-86.

Copyright © Herito 2020