Rumunia - Romania - România

Finis Saxoniae and the Art of Return

Publication: 15 October 2021

Rumunia - Romania - România

Finis Saxoniae and the Art of Return

Publication:

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESTo my parents and grandparents

A Mioritic space of beauty[1]

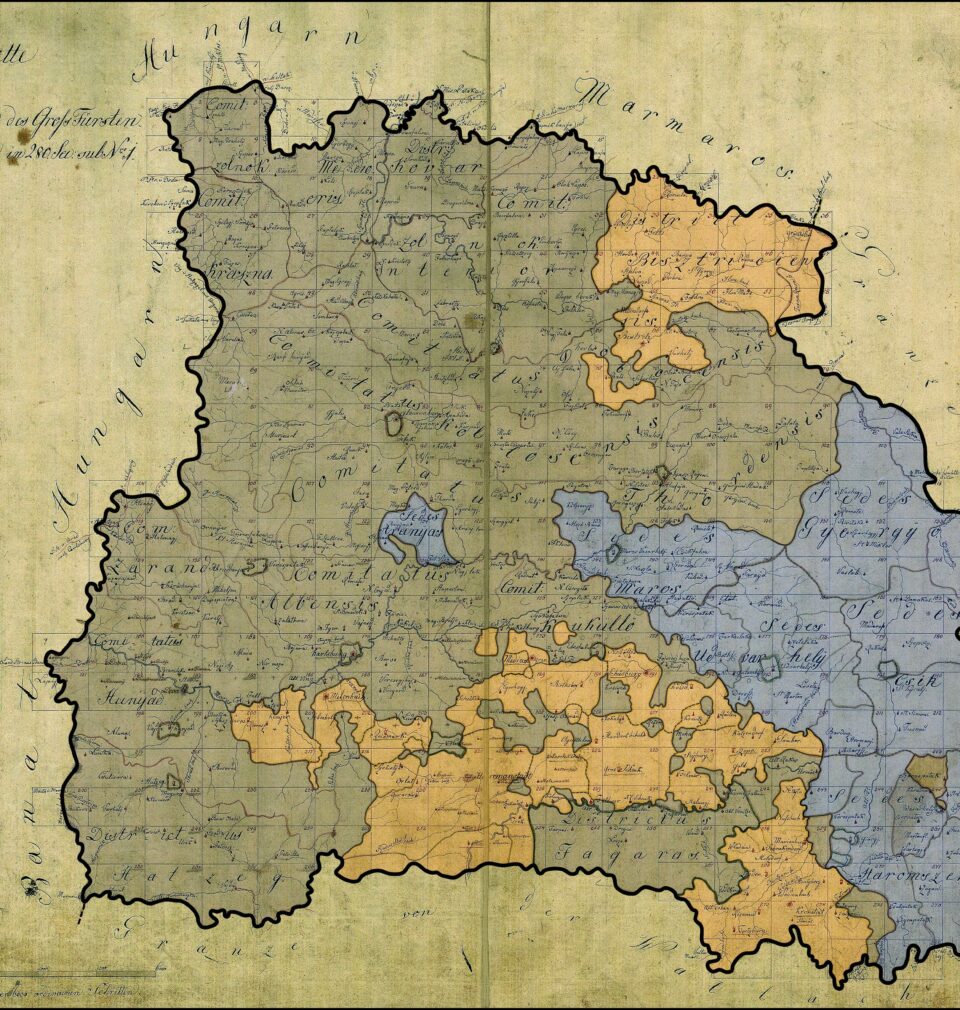

The state accord signed in 1943 between Bucharest and Berlin heralded the start of the compulsory – although nominally “voluntary” – enlistment of Romanian Germans into the SS, a “foreign” army. They volunteered willingly, of course, many of them even enthusiastically. This was a catastrophic rape of their own tradition, and was to cause the collapse of the German community, albeit with the far-reaching complicity of the Romanian state. The final blow to the Transylvanian Saxon community[2] came in 1990 with the mass emigration of this ethnic group to Germany. They left some 250 towns and villages completely depopulated. Peter Jacobi, a Transylvanian sculptor, succeeded in conveying the resonant emptiness they have left in his book of photographs entitled Pelegrin prin Transilvania. The volume contains images forming a heartrending, arresting picture of abandoned, devastated villages, churches, strongholds, fields and ruins. Names such as Abtsdorf, Wölz, Kerz, Arkeden, Draas and Halvelagen to this day also stir distant memories in me. Kreisch, Wolkendorf, Klosdorf, Jakobsdorf, Hamruden, Wurmloch, Denndorf – places I once worked as a village schoolmaster. And I could list maybe even 200 more place names – Pruden, for instance, where my grandfather was born, Hetzeldorf….

The decline of Transylvanian Saxon fortunes began suddenly, in 1867 – or 1876 – with the designation of the community as an ethnic minority and the abolition by the Hungarians of the “fundus regius”, the right to land. This loss cast the Saxons into the throes of complexes; they developed a sense of inferiority and historical non-existence that drove them to the edge of an abyss. It was at this point that the first integrationist tendencies stirred, later to evolve into strivings to join the Reich in the hope of gaining a land of their own. This chauvinistic enthusiasm of the Romanian Germans for the German Reich was presumably born back in 1871, at the moment the Reich itself was born. Prior to that point, the Transylvanian Saxons had enjoyed the protection of the status of “nation”, and Germany had been of little concern to them: they had had their own administrative system, a Saxon diet (the Sächsische Nationsuniversität) and a Graf as their leader, their own judges, appointed by the community, town laws, and schools in every village, even the smallest (they were the first community in Europe to introduce compulsory schooling for all). The Romanian majority was not a party to the “Unio Trium Nationum”[3], did not participate in the Transylvanian parliament, and had no rights.

The history of the Transylvanian Saxons was always, of necessity, a defensive war against the passage of time. Even in the sad years 1940–1944, when the Romanian Germans, led by the Transylvanian Saxons, were politically subsumed into Nazi Germany. This may, of course, be interpreted as an attempt at self-preservation, but the dire consequences of integration with the Reich did not pass them by. The Reich became a moral reference point for the Romanian Germans, for it embodied at once national ideals and poisons, and did so throughout the Wilhelmine period, through the years of Hitler’s rule, and up to the catastrophe that was the Second World War. And this latter was to prove their end.

România Mare

The First World War and the defeat of the central powers – Austria-Hungary and Germany – came as a great blow to the Transylvanian Saxons, and indeed all Romanian Germans. The Kingdom of Romania had been on the opposing side – among the victors[4]. Pressure from France and Great Britain had brought about the fulfilment of promises made at the start of the war: pursuant to the Trianon Pact of 1920, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, Transylvania and part of Dobruja were awarded to Romania, thus augmenting its territory by a half and its population by over a quarter. This created a multinational country, with 19 national minorities: România Mare, Greater Romania. But Romania had had no prior experience with minorities. Moreover, its state system was based on the French model of a unitarian, single-nation state. This naturally disadvantaged the minorities, above all the Saxons and Hungarians, who suddenly became citizens of a foreign, previously hostile state, and the Transylvanian Romanians, who until recently in the ranks of the imperial and royal army had been forced to fight against their own compatriots.

But let us go back in time slightly. The first of December 1918 proved a great disappointment to the Germans. Their initial optimism and hopes that the new Romanian state, drawing on the experience of its Hungarian neighbour and by dint of pressure, would treat the German minority kindly and evince sympathy for their special status, were dashed. In November 1919, on the crest of those hopes, they had put forward their postulates to Romania at the fourth session of the Saxon parliament in Schässburg[5]. None of them were met. There had never been any vast landed estates in Saxon Transylvania, but the “community land”, once the “royal lands”, the foundation on which their small farmsteads had operated, was expropriated. The Church also lost over half of its lands, which had been the financial mainstay of culture, in particular schooling. This forced a significant increase in the church tax.

Not only a considerable proportion of the population, but above all the Saxon banks were hit hard by the “debt conversion” (a phrase cursed in our family), which was based on an unfavourable exchange rate of crowns to lei. This caused a degree of impoverishment that even the banks, which often donated ten per cent of their revenues to social causes, were unable to cope with. This was a crushing blow to the hitherto wealthy Saxon economy, and led to deep dissatisfaction in the wider population, including leading conservative and Church circles, whose representatives had signed the treaty on union with Romania. A “movement of the dissatisfied” was founded, along with Rittmeister Fritz Fabritius’ “Movement for Reciprocal Assistance”, both of which initially had aims of an economic nature, calling for preferential loans and home building programmes, but gradually drifted towards national socialism. As early as 1922 the Transylvanian Saxons came out in support of Hitler’s putsch. Civil servants of non-Romanian descent lost their jobs, replaced by Romanians. Chauvinistic attitudes gained currency. Official posts were filled by people from the Old Kingdom, who were completely insensitive to the situation of national minorities. This was unpopular even with the Transylvanian Romanians.

The primary reason: Nazism

Most Saxons remain in denial about the reason for the demise of their people. Their end, played out before our eyes, a historic end, irreversible and drastic, the result of an increasing infatuation with the Reich from 1940 (under the powerful influence of the political elite and the many military personnel enlisted to the ranks of the SS), is incontrovertible. It bears the hallmarks of treason, and is unprecedented anywhere in tradition. Yet most Romanian Germans refuse to accept that part of the guilt for their radical break with that tradition lies with them. Roland Albert, a former SS officer and one of the main protagonists in my documentary novel The Druggist of Auschwitz[6], says in the book: “In the 1940s we were ground up by the mills of history, but no-one can be blamed, not even our political leaders.” These leaders were a bunch of oafs gathered around Volksgruppenführer Andreas Schmidt, son-in-law of Gottlob Berger, an SS officer in the general-equivalent rank of Obergruppenführer, one of whose duties was recruitment to the SS. Schmidt is partly responsible for the signing in 1943 of the dreadful agreement between Bucharest and Berlin that provided, inter alia, that virtually all Romanians of German descent eligible for military service were automatically enlisted into a foreign army, into units of the SS. Many of them later did service in concentration camps. This was also the lot of Victor Capesius, a Romanian captain press-ganged into the SS and appointed camp pharmacist in Auschwitz. He says: “We were not Nazis; as always, we acted in good faith, as Germans. And the tragedy of our small people is one element of the downfall that met the entire German nation in those times […].” And in this way truth becomes entangled with lies, forming one great pulp, and refuting all responsibility.

In order to analyse these internal “fields of time” I use excerpts from this novel about the “druggist of Auschwitz” and from the book Vaterlandstage und die Kunst des Verschwindens[7] (Days of the Fatherland and the Art of Disappearance). The latter is but a fraction of the 6,000 pages of materials archived in files. Its narrator, sentenced by a Communist court, cannot return to his home town of S. in Transylvania. In his stead, he sends Michael T., the main protagonist of the novel.

The materials on the “druggist of Auschwitz” and the “days of the Fatherland” – and also those used in the third part of the trilogy, the novel Transsylwahnien[8] (title deliberate[9]!) – include stacks of letters from the period, records of conversations with members of my Romanian-German family between 1976–1985, including with SS officers, and with the druggist of Auschwitz himself, Dr Victor Capesius, formerly the pharmacist in the “Zur Krone” (Crown) Pharmacy in my native town of Schässburg in Transylvania.

The main theme of the book Vaterlandstage…, and also of the novel The Druggist of Auschwitz is the issue of guilt. It is natural that the experiences and conclusions of this small group of Romanian Germans embroiled in crimes and the resultant apocalypse not only overwhelmed but shook the very foundations of their defensive system, which was founded on the tactic of denial. They themselves never took categoric decisions that might have forced them into anything, even such as emigration. On the contrary, they perceived themselves as victims of dictatorship – red dictatorship, never both systems – and there was never any question of a sense of guilt.

I would like to mention the text Die Neue Schuldlosigkeit[10] (The new innocence) by Joachim Wittstock, a writer and critic from Hermannstadt[11]. After profound analysis, Wittstock reaches the conclusion that Romanian-German writers have – in the context of both dictatorships – a problem with “the recognised sense of guilt”. This may, of course, be extended to the entire community of Romanian Germans. This refuted sense of guilt is the subject of my research and of my book Vaterlandstage... Wittstock speaks also of a “third guilt” – of a sense of absolute innocence.

This is a reference to the Transylvanian Saxon consciousness prevailing between 1976–1985 with echoes of the 1940–1944 period, which led the Romanian Germans to consider themselves to have been in full Gleichschaltung with the school, cultural, Church and social systems of the Nazi Reich, hence forming a “perfect”, powerful, arrogant enclave of the Reich within Antonescu’s Romania. Since the period 1940–1944, the history of the Romanian Germans has been an inextricable part of the history of the Third Reich, with all the historical, morally negative, and contemporary, practical consequences of that fact.

Stories of the great “time of the nation” (in the sense of the medieval definition of “people”) were like a fairytale, like a dream that continued to play on the consciousness. It is thus small wonder that the “popular” watchwords and the Nazi slogans about heroism worked like charms. “We have always stood together”, “we had German hearts”, my interlocutors would say, but when I asked about “that”, “I didn’t have a German heart”, or I was “digging about in sordid affairs”. Sometimes they spoke to me of a “lack of instinct” or even of “betrayal”. Faith in “the people”, believing themselves to be a part of that people, and taking care not to “sully a great past” were paramount. These went hand in hand with the most important instrument reinforcing the denial: the aesthetic element, i.e. what was referred to as beauty, nobility, heights and spirituality, entirely removed from reality and history. This “beauty” allowed them to forget the “grey day”, and, they claimed, “elevated” them. Most spoke of “feeling”, of the type of sentimentalism that “moves one to tears”. The epitome of this “beauty” was syrupy Saxon street songs, rural choral hymns, and a weakness for operetta in small towns.

Gerhardt Csejka, in his essay “Der Weg zu den Rändern, der Weg der Minderheitenliteratur zu sich selbst”[12] (The road to the edges, the road of national minority literature to itself), writes about the same phenomenon: about how “the overweening, powerful faith in the popular character of the Saxon community is still alive”, even though the community itself no longer exists. “In this way,” Csejka writes, “literature assimilates a role appropriate to the attitudes and behaviours of the previous age – it is still limping along behind itself.” Further, he expresses his opinion that the writers Wittstock, Meschendörfer and Zillich are engaged in “projects” from the generation of Michael Albert[13], right out of the previous century. He also writes that even after the drastic historic crisis of 1944, the main pillar of the trilogy Fünf Liter Zuika (Five Litres of Palinka) by Paul Schuster (b. 1930) is still the notion of a “representative”, realistic and “positive” Saxon historical novel without history or “the people”.

But let us return to the Saxons and their “beauty”. Former SS-man Roland Albert, who features in the book Vaterlandstage… as Andreas, said: “Where others lost their heads… I was tough and unbending… it didn’t affect me as it did other people. I was more unmoved than the most unmoved.” And he adds a convoluted explanation: “Well, but then art, music, and above all poetry often helped me to escape, even there….” That “beauty”, then? As if he needed something else in that grey reality, a reality a little greyer there than elsewhere.

Untersturmführer Andreas, lieutenant and lover of beauty, proved the extent of the kitsch potential in Hölderlin, in the pocket edition of his poems, which he would read up in the concentration camp guard tower. In an interview in 1979 in Innsbruck, he recounted how he was constantly “committing misdemeanours on his watch”, which he would spend up in the watchtower “with his nose in a book”. He was an avid reader of Nietzsche and Hölderlin, simply “not to have to look at all that”. He was a good pianist despite having suffered injury to his fingers in battle at Moscow; unfit for active service at the front, in 1942 he was moved to Auschwitz.

In his thoughts he repeated “inter arma silent Musae” – in wartime, the Muses are silent. “So,” he said, “I did my guard duty with a backpack full of poems. I was constantly committing offences.”

From 1940 the Transylvanian magazine Kirchliche Blätter began to print curious poems. One example: “Lord God / protect the Führer / may his work be Thine / may his work be Thine / Lord God / protect the Führer”. Or these lines by Heinrich Zillich, the most “worthy” Saxon author, written in honour of Hitler: “Sent down to the Germans from God […] Good, blue eyes, hand of bronze, armed with sword / low voice, dearest of fathers to children […].”

I have often had occasion, also in Germany, to observe men of that generation, in moments of weakness, their mendacious, false pathos and affected feelings. But that pathos and kitsch even pervaded the most critical minds of the age, such as Karl Kraus. Even Klaus Mann wrote a novel, Mefisto, with Gründgens[14] as the prototype for the main hero. Nazism was characterised by the artificial facades of a confabulated world that craved the natural and genuine but was in fact their opposite – that world, sentimental and teary, was saturated with an enthusiastic kitsch that emanated from every sphere of life, including its art, its monumental buildings, films and speeches. It was this kitsch that presented mortal peril, particularly in speech, this “overflowing soul of the people” with its mass of “feelings”, yet completely isolated from politics and reality, that made possible the war and gave its acquiescence to concentration camps, to an everyday reality that evolved into unimaginable factories of death – on whose peripheries officers and their families, celebrating Christmas, sang German carols, staged concerts, and recited poems. Art and barbarity. Hermann Broch, in his lecture “A few words about kitsch”, offered a very early warning about the impending danger: “the connection between neurosis and kitsch is not without significance in the historical sense”[15]; “it is no accident that Hitler (like his predecessor Wilhelm II) was a great lover of kitsch”[16]. It is common knowledge that this was an affection to which other dictators, among them Stalin, also succumbed. Broch defines kitsch as imitation, simulation, blatant lies, and feigned feelings elevated, dangerously and alluringly, to “sublimity”. “Look, they stand in processions on vast swathes of land / woman with man, their souls aflame, / in holy fusion…,” writes Heinrich Zillich[17], for instance, addressing Hitler.

The thesis that the Transylvanian Saxons are “irreligious”, as one of the first Nazi visionaries and crypto-fascist theoreticians claimed, does, alas, find confirmation from the angle of the psychology of peoples. It is also true that the “notion of nation”, as Alfred Pomarius claimed, acted “as a religious substitute […] in the place of the notion of a god”. Pomarius defined this “pull toward rationalism” as a “type of religious life”, as an “economic and political religiosity”.

The aesthetic substitution of various kinds of “feelings” for religion – above all the supremely valued “community”, “German soul”, and values such as duty and obedience, would not have been possible without Hitler and the death camps. We should remember that Hitler called conscience “a Jewish invention”. “Pedantry” and “playing the wiseacre” are “Jewish traits”. My Saxon interlocutors accused me of “negativity”. I quote: “It’s sad… you don’t feel it any more.” “But I do… only I don’t accept that part of myself….” “You don’t accept it… but it’s… your better part… You don’t have a German heart.” If one treats these “feelings” too bluntly, one encounters immense irritation; as if they were a religion, and hence sacred.

The term used in psychiatry to describe those regions between waking and sleeping with which forgetting (e.g. dreams) is associated, is the “borderline between states”. These borderlines can also refer to the sense of time, and to moods, however. My interviewees claimed never to have heard of “Auschwitz”. The word “Auschwitz” today has a different meaning than it did then. They were not lying. My own experience told me to answer my own question of whether the individual has any way of resisting the influence of the times in the negative. During those interviews, I said: “Perhaps I would have been a camp guard too, I don’t know. Perhaps.” To which my interviewees responded: “Perhaps?! Perhaps?! Definitely!”

The time of the red dictatorship

The twenty-third of August 1944. The rays of the morning sun glimmered through the branches of the nut tree. The sound of bells reached us from afar. The lanky milkman, the metallic clank of milk churns. He came to a halt alongside us and said: “Stiţi doamnã – vin ruşii”. “Kurt!” my mother shouted, terrified, “The Russkies are coming!” A sudden reversal. Time stopped…. All our plans gone to the devil. Everything gone to the devil, although nothing has changed.

It wasn’t “liberation”, but “defeat”, because the Saxons, the Romanian Germans, had been on the “other side”, of course. What we have to remember is that until May 1945 the men had fought in divisions of the SS and the Wehrmacht, some of them had held posts in the camps. Considered “Nazis”, 99 per cent of them were nevertheless a “national group” (“grupul etnic german”). Hitherto the perpetrators, they were transformed into a collective victim. The twenty-third of August stripped them of all their rights. In January (on “black Sunday”) some 30,000 people (men aged between 18 and 45, and women between 18 and 35) were transported to the Donetsk Coal Basin as labour. This operation, carried out at the Soviets’ behest, provoked the (futile) protest of the Romanian government, which attempted, with the support of the Allies, to halt the deportation of these Romanian citizens.

My aunt Friederike told me that one of those deported was my uncle Georg. He received the order from the Russian commandant of the town: Report! In this same way – on an order of the commandant of the town – the Germans had once summoned Jews. Uncle Georg’s response to this was: “Very well, very well, I shall go. May God protect you, my love, you and the children! I shall return before long; after all, I am healthy.” He took his backpack from the table, laced it up carefully, went to the door, and stepped out into the corridor. And never came back.

Some, like my father, went into hiding; others changed their names, or married locals, like Lieutenant Popescu, who married Gret. To this day she continues to receive a Romanian officer’s pension for him, even though she has been living in western Germany, the “new homeland”, for years.

The Act on Minority Status passed in the first days of February did not initially extend to the Romanian Germans; they were stripped not only of their right to take part in elections, but also of their Romanian citizenship. Most of them lost their jobs. Even their school buildings were confiscated. They were detailed for forced labour, subjected to persecution, but not resettled, as in Yugoslavia, Poland and Czechoslovakia. The Romanian Germans were valued as an intelligent and reliable workforce.

My father and uncle sat at home and took on physical work, digging up grass from the sports pitches, or making toys; the women knitted; and I, 13 years old, had to help the adults, for instance chipping limescale from the vats in the leather works, or weeding the garden.

On 23 March, pursuant to a new agrarian law, most German farmers were expelled from their homes, farms and land. A similar fate befell the townspeople. German businesses were expropriated. The only people spared this treatment were those who had fought in the ranks of the Romanian army after 1944. Everything that could serve as the basis of the community – schools, institutions, property – was destroyed. We became aliens in our own homeland. On 30 December 1947 the “people’s republic” was created and the king was forced to abdicate. This was the beginning of the Stalinist Sovietisation period, which meant that the Romanian Germans were treated in the same way as everyone else: they were no longer persecuted as Germans but as a class. On 11 June 1948 all private property was “nationalised”. On 9 August schools all passed into the hands of the state; the only exceptions were German church schools. In 1950 the next phase followed: expropriation of residential buildings.

Blow after blow rained down on us. I still remember it well: as every day, around seven in the evening Grandfather S. and my father came home from their work at our plant A.V. Hausenblasz. They had taken the plant from my grandfather. From then on the life in him began to fade; he tortured himself and worried himself sick. Father would say: “His life’s work was ruined, he couldn’t come to terms with that. First there was the affair with the limited partnership: he reorganised the firm, changed its name to Elegant Works, and went into partnership with some Romanians and Jews to try and see the hard times through. But that proved a fiasco too. Shortly after that, slowly but surely, the expropriations began. That was what they wanted, precisely that. Most of all they would have liked to eradicate us altogether. And our young people still in Russia. It was all over. Our life’s work. He had made his way out of terrible poverty, worked for what he had. But now? All over, all for nothing….”

“It was the beginning of summer, a cloudless June, 1948. One day, a terrible rumour spread. Mrs Flechtenmacher came round,” my mother recounts, “and said that they would be taking everything away from us….” Did the scales fall from their eyes then? Was that the fall from heaven that the great Adolf had spoken of? The fall that could have been heroically averted by sending their opponents into kingdom come?

I remember how one day my father came home and said, in a worried voice: “We have to pack at once. Within 48 hours the house must be empty. They’re expropriating it. The security service is moving in.” When we had taken all the furniture, curtains and rugs out of the rooms, the house began to reverberate with hollow sounds. Steps echoed, and the sounds of conversations emerged as if from a great distance.

Writing as life after death

Romanian-German literature addresses the theme of the end. Its success is assured by the pathos of parting, the “swan song” after the historic fall. Language records the states to which it succumbs itself: “The high sky like the navel of nothingness, / the typewriter dead, and the peace / absolute”. These lines issued from the pen of Franz Hodjak, an expert at parting.

My own writings and my experiences from my last travels “home” show me, whether I like it or not, that the chaotic new post-1989 reality that has taken root in the towns and villages is merely a reflection of an inner state, and one that is dangerously opening up old wounds. What has been forgotten is fighting its way back out into the light with all its might. Reality, like déjà vu, is becoming schizophrenically confused with forgotten images and nauseating, dizzying scraps of dreams. Is this the revenge of the forgotten “homeland”? The boundary between reality and hallucination is becoming dangerously effaced.

Under the dictatorship, “‘home’ was no longer a ‘place’,” Herta Müller wrote in her book Barfüßiger Februar (Barefoot February). Christa Wolf wrote of the GDR as a place that did not exist, anywhere. A squandered, wasted life. The security organs of the Securitate and the Stasi created a situation of a permanent state of emergency, of an irrational reality; wherever all forms of public life were eradicated, a community bonded by the solidarity of fear emerged, in defiance of the state security service and the censorship. For Herta Müller, emigration freed up what had previously been “stagnant time”. The revolution of 1989 did so in an even more radical way. “Stagnant time”, mirages of space. As if reality had been invented by a crazed poet, as if it were a plagiary, a fraud.

In his novel Ausreiseantrag (Application for emigration) Richard Wagner writes this about the deception, the artificial reality of halted time: “He saw carnations that looked deceptively like carnations… He saw cafés deceptively like cafés. Today there is no coffee. He leafed through newspapers deceptively like newspapers. The sports news, that was all you could believe; all the rest was deception, a lie.” All this is constantly reminding us that this was shelved, artificially halted time.

This groundbreaking experience is condensed in this small literature to the format of epic truths: illusions of space, time and the logic of language are unmasked. And while western readers find this state of consciousness hard to understand, it affects them in equal measure, and in this way conditions the new aesthetic of paradoxical logic.

The repositioning of the world into the fragile web of language as Hensel, Werner Sölnner and above all Oskar Pastior do it shows that extreme phenomena, in spite of their paradoxicality, do go together. Pastior does this using variations in the sounds of what is “in-between”, and through a remarkable diversity of associations. This release of language inspires the reader, who is “inawordthroughandthroughrevived”, even if Pastior attributes to language purely mathematical forms, as in his volume of palindromic verse Kopfnuß, Januskopf[18] (1990).

Language as the last homeland, a homeland in the mind. In my own volume, too, Aufbäumen (Objection, 1990), the poem Rewohlt addresses the double meaning of the word “expelled”: “What would still be / has no neck / up now: the gallows is / a feather”. And yet thanks to language, all is not lost: “Something has ended, unnameable / between language and death, but he / flies, otherwise he would be dust, above it all. // And they said you survived.”

Authors die, chilled by western coldness. Three authors committed suicide, two – Georg Hoprich and Roland Kirsch – while still in their homeland, while the third – Rolf Bossert – took his own life shortly after his arrival in Frankfurt. “And you, o so lucky one / did you think life was yet to start? Nothing is improper, / I breathe glass. A concrete apple in the grass. The devil take language.” Those are my lines, written after Bossert’s death.

The dictatorship honed the delicacy and sensitivity of language in its most subtle areas, controlled writers, censored them, persecuted them, opened up the chasm of the absurd, and attuned authors’ senses to absurdity. To this must be added the decline of the language, and a logic leading to the absurd. The dictatorship exerted constant control over language; it was a serious, palpable threat. People living to the rhythm of slogans and set phrases develop an aversion to explicitness and formulaic expression – a physical aversion that intensifies in writers and leads to a rejection of all that is purely real in nature. As in Oskar Pastior.

The vacuum of absence, “headless pillows on kisses without lips”. What during the Cold War was executed by force in the East was in the West opposed to the system without any pressure. “Not everything is in order, but OK,” as Werner Söllner writes in his immensely moving monologue (Monolog), which begins with the words: “It would appear that I have died.”

Translated from the Polish by Jessica Taylor-Kucia

***

[1] This name is taken from the folk ballad “Mioriţa” (the little ewe), the greatest and most famous work of Romanian pastoral lyric poetry. In a reference to the spiritual space in which the drama constituting the plot of the ballad takes place, Lucian Blaga (1895–1961), poet, philosopher, essayist and a native of Transylvania, coined the term “Mioritic space” to describe a landscape as the spatial and spiritual matrix for the people living there. In his definition it is a “high, indefinably undulating space” in conjunction with a spirituality “strung between a muted fatalism and trust”. The Mioritic space is one of the central categories of a description of the unique Romanian spirituality, but it also speaks of a “bond of soul and space”, which was undoubtedly a major consideration in Dieter Schlesak’s choice of reference.

[2] Transylvanian Saxons – one of the major ethnic groups of Romanian Germans. They settled in Transylvania in the 12th century under the rule of the Hungarian king Geza II (ed. note).

[3] The “Union of the Three Nations” (Lat. Unio Trium Nationum) – a pact concluded by the Hungarians, Saxons and Szeklers in 1437 in response to peasant rebellions. It confirmed the privileges of the three national estates and their readiness to put down similar uprisings in the king’s name in the future. The Wallachians (Romanians) were excluded from the agreement (ed. note).

[4] Kingdom of Romania – name of the Romanian state between 1881–1947. Here, in the sense of the “Old Kingdom”, otherwise known as the Regat, which comprised Moldavia and Wallachia (ed. note).

[5] Schäßburg (Ger.) – Rom. Sighişoara, Hung. Segesvár.

[6] Dieter Schlesak, Capesius, der Auschwitzapotheker, Bonn 2006; Polish edition: Capesius – aptekarz oświęcimski, trans. Renata Darda-Staab, Kraków 2009; English edition: The Druggist of Auschwitz, trans. John Hargraves, New York 2006.

[7] D. Schlesak, Vaterlandstage und die Kunst des Verschwindens, Zürich 1986.

[8] D. Schlesak, Transsylwahnien. Roman [e-book], [no place of publ.] 2009.

[9] A pun: Wahn (Ger.) – madness, lunacy (trans. note).

[10] Joachim Wittstock, “Die Neue Schuldlosigkeit” [manuscript], 1990.

[11] Hermannstadt (Ger.) – Sibiu.

[12] Gerhardt Csejka, “Der Weg zu den Rändern, der Weg der Minderheitenliteratur zu sich selbst”, in: Neue Literatur 1990, book 7/8.

[13] Michael Albert – American economist and alterglobalist, one of the creators of the concept of participatory economics (ed. note).

[14] Gustaf Gründgens (1899–1963) – the most popular German actor of the Third Reich (ed. note).

[15] Hermann Broch, Kilka uwag o kiczu (lecture), trans. Danuta Borkowska, in: idem, Kilka uwag o kiczu i inne eseje, Warszawa 1998, p. 116.

[16] Ibidem.

[17] Heinrich Zillich (1898–1988) – a Saxon born in Braşov, a writer, one of the foremost proponents of Romanian-German literature (ed. note).

[18] A pun: Kopfnuss – 1. a knock, blow to the head; 2. a conundrum; Januskopf – Janus’ head (trans. note).

Copyright © Herito 2020