Conflicts of Memory

We Have Constructed Europe. Now We Need to Construct Europeans

Publication: 27 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESLet us harbour no illusions about it. In a situation where big capital cities are bound to dominate Europe, especially such domains as foreign policy, even if the Council was presided over by a politician from another country, it would not change a thing. The interests of the largest countries, including Germany and France, are not always compatible with the interests of Estonia or even Poland. They will never give up their interests for the sake of Europe.

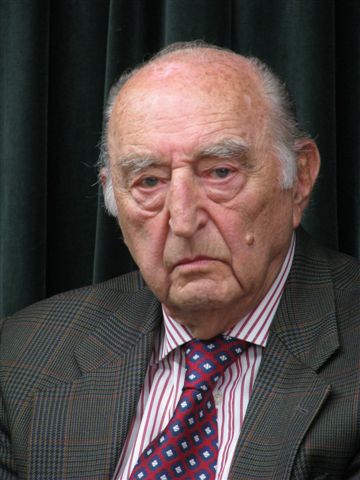

Katarzyna Romańczyk: How do you remember Brussels from when you came here for the first time during the 1950s?

Leopold Unger: I first visited Belgium in February 1956. For Poles, it was the great October year; for Belgians it was the worst winter in a century. It had been a very long time since they had had such cold weather. For me personally, it was an important experience. Never before had I spent so much time in the West. In addition, major events took place in Moscow. It was the year of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Nikita Khrushchev’s famous “Secret Speech”. That’s why the clash between (my) perception of the West and what was going on in Moscow was forever stuck in my head. They had democracy and freedom of the press here. I was intrigued by that. During my first visit to Brussels, I was attended to all the time, so I failed to notice anything that might enable me to create an image of things. My second visit to Brussels was in 1958, to an Expo, which I found tremendous. In fact, I spent most of my time at the exhibition. I saw the world. I came to Belgium to settle permanently in 1969, and found it completely different from the city I had seen in 1958.

K.R.: In what way was it different?

L.U.: New structures, such as tunnels, had emerged to forever influence the growth of Brussels. They had dramatically changed the image of the city, which, to a large extent, they ruined, although, at the same time, they did not smother it. The Central Station had been built. The underground transport network had been introduced between the northern and the southern, the western and the eastern parts of the city. I did not see these things as urban architecture – to me, they first of all were about comfort. And you remember comfort much better than urban transformation.

K.R.: Especially when you are an emigrant?

L.U.: As an emigrant, in the initial years after arriving, you do not pay much attention to what’s around you, to the hallmarks and landscapes of the city. At the time, I had to ensure my financial stability. In 1968, as we all know, there was only one place that the Jewish people could go, namely, Israel. Having left Poland, I could only travel to places where I was welcome. My wife and I decided to come to Belgium, because our family had wanted us to come here and they prepared the entire “logistics” of our arrival to a foreign country without cash. Consequently, in my early emigrant years, I was mainly preoccupied with ensuring financial stability for myself. I considered a number of options to eventually return to my trained profession.

K.R.: Taking the job at Le Soir offered a wide range of educational opportunities…

L.U.: Working at Le Soir, Belgium’s biggest daily newspaper, I wrote articles about the East. Throughout the Cold War, I dealt exclusively with the Soviet Union, Poland, and the former Eastern Bloc countries. I was working so hard that I hardly had time to get acquainted with Belgium, really. If memory serves me well, at that time, I only visited Antwerp and Bruges once, but I never had the chance to go to Liège. Strangely enough, I have never really acquainted myself with Brussels and its residents. I do have some friends, but I have never become part of Belgian society, even though I had all the resources I could possibly need at my disposal. Being a Le Soir expert on Eastern affairs, rather than meeting Belgians I met other experts like myself. Belgians were only my readers. Later, when Brussels developed as a European metropolis, I never had the opportunity to meet a true Belgian. I instantly became part of the international Brussels ghetto.

K.R.: In Brussels, have you met Polish people who complain that they are second grade citizens?

L.U.: I have met all Poland’s ambassadors to Belgium, but I have never been familiar with the Polish community. I guess there is no such thing here, but there are Polish classes. In my opinion, the so-called “Polish community” in Brussels is more or less analogous to the country’s social structure. In Brussels, there are many peasants, chiefly from the Białystok region, as well as peasant women, who work as housemaids, which is a high value occupation. There’s also a group of young emigrants who have been totally inactive in the Polish community and have swiftly integrated into the Belgian community. Young Polish doctors live just like young Belgian doctors, and they socialise with Belgian doctors far more readily than with other Poles, who come here to work. I see Polish people at classical concerts in Brussels, but they have nothing in common with Polish workers employed by Belgian companies.

K.R.: Does the Brussels you know have a genius loci?

L.U.: It does! Two… Maybe even three. I mean the old Brussels, the Marolles district, which has been gradually shrinking. They have demolished many old buildings and their residents have moved elsewhere, but a genius loci has remained. Genuine Brusseleirs (Brusselians), who do not speak French or Flemish but a Brusselian local dialect, are on the verge of extinction. Is there such a thing as a native Brusselian? I’m inclined to wonder. Most importantly, we must consider how many people come to work in Brussels, every day, and how many sleep outside the city. These people spend the money that they earn in the capital city in their provinces. The ring around Brussels is growing rich, while the city itself is getting poorer. But – besides the fact that it is a region, just like Wallonia and Flanders – the city enjoys a high degree of autonomy. You could say that you’re a citizen of the Belgian, the Francophone, the Flemish, or the European Brussels. You could divide the city in many different ways, and in each part you will find a unique atmosphere, culture, community, etc. In spite of appearances, Brussels boasts a rich, vibrant, and diverse cultural life. Two, or maybe even three cultures co-exist here, enjoying equally impressive cultural activities. European and international cultures have also been promoted, for example, through the Europalia arts festival.

K.R.: What do you think about the presentation of Polish culture at Europalia 2001?

L.U.: It was really bad.

K.R.: What went wrong?

L.U.: It lacked class. The French one was also below standard. The Portuguese and Chinese presentations were more interesting.

K.R.: Art activities aside, the cultural life of Brussels has been contributed to by the city’s foreign-born population.

L.U.: The international community has its own separate life. Sadly, this great cosmopolitan spectacle has never influenced the life of Belgians in Brussels and the other way around.

K.R.: Do you mean that there’s no melting of cultures?

L.U.: Even within the international community, the Eurocrats have built a ghetto. They have their own clubs. I avoid European institutions, because they are overwhelming. I find the European Parliament impossibly pretentious. This situation has been slowly changing, because the Treaty of Lisbon is aimed at improving the operation of EU bureaucracy, but it will not make the already-existing institutions smaller. Conversely, the international community will grow even larger. It is a business that operates according to its own rules.

K.R.: Isn’t it paradoxical that Brussels, which has become a symbol of European integration, is also a bone of contention between Flanders and Wallonia?

L.U.: It is not paradoxical. Belgium lives the way it wants to live. Walloons do not get along with the Flemish, because they do not want to, chiefly due to the obstinacy of the latter. I don’t blame the Flemish, far from it. It is a very natural reaction of the community, who take vengeance for the decades of oppression inflicted upon them by the Francophones. Some Belgian friends of mine claim that the Flemish are only fit to work as servants. It was Europe that wanted to unite. Its leaders met up in 1957, to establish the European Community.

K.R.: Can Belgian federalism be regarded as a model?

L.U.: Today, the federation cannot function normally due to a silly, parochial conflict concerning Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde. This is really paradoxical, if you ask me. The fate of the Belgian federation, a flourishing state, can depend on the way a single district in Brussels gets divided. All this stems largely from the stubbornness of both sides. In Belgium, there are two completely credible, independent countries. Wallonia and Flanders (in particular) have everything they need to be sovereign.

K.R.: What is the superior power that connects these two independent countries?

L.U.: Common sense, according to which it pays to be together, economically, some institutions, such as the monarchy, and, above all, the status of Brussels. Flanders will never give up Brussels, and neither will the Francophones.

K.R.: What do you find most surprising about Belgium, where, like you have said, few really know what the purpose of the state is?

L.U.: There are at least five parliaments in Belgium. Can you think of another country, which has five parliaments?

K.R.: Does this surprise you, though?

L.U.: I pay a large tax bill in Belgium and I believe I do it in order to make it a peaceful place. And peace will come when more autonomous regional institutions emerge. In Wallonia, there are many intergovernmental organisations. They’re there to provide jobs to people. Belgium is managed by political parties, not the government. In order to make a decision in Wallonia, Flanders, or on a federal level, political party leaders first need to assemble. Even the federal parliament is a supplementary institution, passing acts that are first discussed by political parties. The same applies to the languages. Theoretically, Belgium is bilingual, but there aren’t many genuinely bilingual people here. The Flemish are truly bilingual. There are very few bilingual Francophones. When we look at the institutional structure of the state, it becomes clear that the vast majority of executive institutions are staffed by the Flemish, because a perfect command of both languages is required. These days, most Flemish people can speak three languages, including English.

K.R.: How does this mosaic of public institutions translate into the well-being of the average citizen of Brussels?

L.U.: Public life in Brussels is chiefly concentrated in municipalities. The municipality issues passports and IDs, provides money to poor people, establishes parking zones, supplies funds to hospital, etc. It’s not the ministries that solve people’s problems. There is no bond between the citizens and the ministries. There is a bond between the citizens and the municipalities. I have never been to a ministry, but I have visited the municipality very often. I am not a citizen of Brussels, I am a citizen of the municipality of Woulwe-Saint-Lambert. It is my actual homeland, in this respect. The ministry is beyond my reach. I imagine that this sense of regionality, which is extremely strong in Flanders, and quite considerable in Wallonia, has not yet reached such levels in Brussels. In the capital city, even considering its cosmopolitan character, everyone refers to himself or herself as a citizen of Belgium rather than of Brussels.

K.R.: Is there a tolerance limit between the Flemish and Walloons?

L.U.: Most certainly, especially in Flanders, where demonstrators shout: “Let Belgium die!” Nationalists will not be easy to eliminate. It won’t be easy to get rid of the nationalists. Vlaams Belang is a very racist, anti-Belgian party.

K.R.: Are Belgians xenophobic?

L.U.: I used to say they are not xenophobic, because they hate each other so much that they’ve exhausted their hatred. But I wouldn’t say that today. Some changes have obviously occurred that are mainly connected with the crisis, which have lowered people’s tolerance to each other. The conflicts only involve fighting over money. Flanders believes that it subsidises every Walloon. What deepens the problem is the inflow of Muslim migrants and their poor integration, which has been hindered by the Flemish-Walloon social issues. There is this thing as “civilisation shock”. You don’t really pay attention to it when you’re prosperous. Due to the crisis and the disturbing (almost 18 per cent) unemployment rate in Brussels, an unemployed Belgian will act like a European, but a Moroccan may act very differently.

K.R.: In crises, people’s attitudes become more radical, as a rule.

L.U.: In crises as well as due to poverty and propaganda. There are a number of different forces operating in Brussels. Belgium is covered by a network of mosques, many of which are small, privately owned. I was criticised in some circles, when I meddled in their affairs in Le Soir. Belgians were only xenophobic towards each other. You could sense alienation, but not a hostility. Different standards of living, especially in Brussels, when – due to the crisis – state finances began decreasing, intensified the antagonisms among people. European Union officials pay minimum tax, which arouses further discontent. Belgians know what cars the Eurocrats drive and where they live. If we compared the salaries of a European commissioner or the head of the European Council and those of an average citizen, we would see an immense disparity, which deepens the gap and the feeling of alienation. Envy is the most common and most human of feelings. Poverty makes people less patient and less empathetic towards strangers. It’s normal.

K.R.: The disputes over language and the division of Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde have become inherent to the sphere of political conflicts in Belgium. How do you rate the Belgian political class in this light?

L.U.: Particracy is very strong in Belgium, and, at the same time, the standards of the political class are very high. I will use an example here. Appointing Herman Van Rompuy, the President of the European Council, was the subject of public discussion. Powerful European states have been criticised for the fact that they did not want to make the head of the EU a strong man and an aggressive, tough talker. The appointment of Van Rompuy has not changed anything in this respect. He is a wise, dignified experienced mediator, a prudent man, an excellent diplomat, who can reconcile different posts. Let us harbour no illusions about it. In a situation where big capital cities are bound to dominate Europe, especially such domains as foreign policy, even if the Council was presided over by a politician from another country, it would not change a thing. The interests of the largest countries, including Germany and France, are not always compatible with the interests of Estonia or even Poland. They will never give up their interests for the sake of Europe. To them, all other countries should adjust their policies in their favour.

K.R.: Would you say there is a European public opinion?

L.U.: No, there is no such thing. We have constructed Europe. Now we need to construct Europeans.

K.R.: What do you mean? We are European, after all.

L.U.: The number of citizens of European states, who would think in European terms as opposed to national terms, involves a very long process. The Treaty of Lisbon was supposed to change this. The European Union is not a democratic institution. Perhaps it will become one when the European Parliament begins to operate with modifications that the Treaty is expected to bring. Perhaps the opinion on the isolation of European institutions within the structure of the member states will then change. Where is this opinion if, in Poland, only 20 per cent of citizens vote in the EP election, and only slightly more do in other countries? A Belgian is European in the same way as a Pole or a Dane is European. However, he is Belgian, Danish first, and then he is European. An opinion can only develop when we voters understand that we elect our European Parliament.

K.R.: Many Brusselians criticise the functioning of EU institutions. Is this about populism or do they really mean it?

L.U.: Both. The standard of living of many Eurodeputies is excessively high and it shows. They could live more modestly. I don’t like it. When you enter the European Parliament, you can see a pretention, an almost sovietist touch about it. Sovietists loved huge spacious interiors. The rooms in all Soviet institutions were overwhelming. In the EP, I thought the space was superfluous. The perception of European institutions in Brussels can influence the notion of Europe in a very bad way. A Brusselian, who sees the way the institutions work (I’m not sure whether he sees them correctly), believes that they are a hotbed of privileged bureaucracy, which puts him off the EU.

K.R.: But Belgians, including Brusselians, have supported the Treaty of Lisbon through their federal and regional governments?

L.U.: France, Ireland, and the Netherlands held referenda on the Treaty of Lisbon, which comprises 900 pages of extremely complicated statements. How can one ask the average citizen about his or her opinion on the Lisbon Treaty? Consequently, people in these countries did not vote against the Treaty, because they did not know anything about it; but they voted against the governments, which had proposed it. In Belgium there was no such referendum, but the process was similar. Only that voting is compulsory in the election in Belgium. Bearing this in mind, the 20 per cent attendance in other countries means something, while the 90 per cent attendance in Belgium does not mean anything at all. Elections for the municipal councils, the regional parliaments, or even the federal parliaments are an entirely different cup of tea. The Brussels Parliament election results have been increasingly forged through vote buying. Turkish or Arab representatives are put on lists of candidates, for example. Muslims do not have a party in Belgium, so they vote for the groups who include their candidates in the lists. It’s hardly democratic, because your vote should be based on the candidate’s qualifications rather than his or her origin. In this respect, Brussels is very special in comparison with other regions.

K.R.: What sort of benefits does Brussels draw from its European institutions?

L.U.: Financial ones.

K.R.: Only financial?

L.U.: Mainly financial. It must give Brussels billions of euros each year. Many Belgians are employed in the European institutions, so their income increases. They are well-to-do. They constitute a large group in Brussels. At the same time, however, European officials do not pay local taxes, which, I believe, is outrageous. They use the same infrastructure as everybody else and they do not pay for anything. The fact that these employees spend a lot of money on services provided by Belgians may be perceived by Belgians as compensation for all the disadvantages connected with living in the vicinity of European institutions. In Brussels, there are restaurants whose entire income is the money spent by European officials. But I do not really feel entitled to discuss it, as I am only a beneficiary of European institutions. I’ve managed to combine working in Brussels with my work as an international journalist. I’ve had my share of moments of glory. I have gained respect in the local milieu. I came to Brussels, because I planned it. My family was here and I had their support, and then I realised that this was the perfect place for me. There is no better place in the world for a journalist than Brussels.

Brussels, 1 December 2009

Copyright © Herito 2020