Nations - History and Memory

What Does Europe Need Nations for?

Publication: 13 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESWhat is the condition of the nation in Europe and in the contemporary world? Although the national community was formed as one of the elements of modernity, it is fair to ask about its role or even legitimacy in the period of postmodernism. Has the nation fulfilled its social role, and is it therefore entering its twilight years?

As we all know, each social reality, both contemporary and historical, is passed on to people in words. So in the context of analysing the phenomenon of the nation we should distinguish two aspects: on the one hand the sphere of real events and actions, and on the other the sphere of words, concepts. Although this is a commonly accepted distinction, not all researchers use it in their reflections on causal relations. So the question “What do we need nations for” must be considered from two points of view. First, we must reflect on the concept and definition of a nation, on the word itself and all concomitants. Second, we must consider the social or political reality: I mean here the reality of the social group called the nation. And we must not forget one more element, namely space; we should remember that the term “nation”, although a mostly European phenomenon (and term), is now used in the global context. So studying this term cannot be limited to the European perspective; the concept should be placed in specific spatial frameworks and take into account territorial differences, especially differences between Europe and the rest of the world.

Starting from these basic premises, I would like to analyse and prove three fundamental claims:

First, that in various epochs and languages the concept of a “nation” was and still is used as a description of very varied historical situations and social elements.

Second, communities, the large social groups described using this term, have developed in historical terms and from a typological point of view were and still are – despite the basic common features – very much varied.

Third, the nation as a concept and a phenomenon of national identity is a typically European phenomenon; the term nation was “exported” outside Europe and there, in different civilisations and systems of values, gained a different meaning, in line with local conditions.

Terms have a life of their own

The term “nation” is not a word like any other; it is not used only as a technical term, like, for example, the state, ministry or inhabitant of a city; the word retains a certain emotional colouring and often goes beyond – or seems to go beyond – mere calculation (understood as rational choice).

For most people belonging to a nation was and still is connected with a positive feeling. Representing one’s nation is a matter of honour and one should be happy about its successes – now especially in sport, cinema and technology.

Previously, though, a categorical imperative was present, today rarely encountered: a citizen was supposed not only to draw benefits from national belonging, that is use its existence in his own interest, and perhaps boast of its successes; he was also supposed to bear responsibility for this community. This imperative demanded of the citizen that he be useful for the community through active work for its good and the reputation of its members.

How did it come to that? We are certainly dealing here with a legacy – or liability? – born in the 19th century. Some researchers believe that the emotional content connected with the term “nation” originates from the French Revolution, whereas others derive it from the philosophy of Johann Gottfried Herder, and others still perceive the influence of Romanticism here. The Herderian idea of a nation as a divine creation and the theory of the native language and national culture as an inherent value certainly influenced many of his readers. Undoubtedly one of the objects of Romantic love and enthusiastic admiration was the nation, its culture and history. Chronologically speaking, though, such a spiritual attitude is not the “beginning”, and the search for the reasons of emotionalising the concept of “nation” must start much earlier. For the historical-political and cultural-semantic roots of this emotional element go much deeper.

Let us first consider the cultural-linguistic element. As is commonly known, in almost all European languages the word “nation” is a derivative (or a translation) of the Latin noun natio; and this word stems from the verb nascor (natus sum), meaning that something is part of a specific context by dint of its origin, being born in particular circumstances. As we all know, the term nationes, used at universities and councils, referred to students and Church notables originating from the same region. However, only specialists know that the territorial relations described as natio are not always coextensive with geographical terms used today; but researchers realise that this distinction – used already in the late Middle Ages and regarded as regional – often also accounted for the linguistic belonging. So the concept was already undergoing a certain “nationalisation”, although in the Middle Ages it had little to do with this form of “socialisation” now contained in the definition of a “nation”.

Even on the eve of the modern era, the word natio was used in reference to elites belonging to the same state – in Hungary and Poland it functioned for many centuries in the phrases natio hungarica and natio polonica and described the politically privileged class, that is the gentry. Besides that a group characterised, among other things, by common linguistic features was also described with the Latin word gens. Yet another medieval term is the word lingua (Latin for language), defining a particular linguistic group.

Since the 15th century and above all in the 16th century the Latin natio was commonly accepted and found a permanent place in the developing national languages. From the very beginning the process of acquiring a particular meaning by this term occurred in various conditions, dependent on the political situation in particular European macroregions. But the process can be followed quite precisely since the times of the Enlightenment. On the one hand English lexicons, in line with the political situation, under the term English nation understood the politically coexisting people, its structure ordered by the state. The Grande Encyclopédie too speaks of la nation as the sum of the subjects (or population) living under the reign of one ruler and subordinated to a law identical for all. On the other hand, in the German from that period the term Nation (and its synonym Volk – people) is associated with a common speech and culture. It was similar in the Czech language and most Slavic languages. Regardless of the differences, from early modern times “nation” acquired a positive ring and was associated, for example, with the concept of homeland. Even during the Enlightenment, its representatives published their reflections on the subject of “national pride”. They conducted disputes on national virtues and specific features of particular national groups, which they called nations. They were also interested in identifying “national enemies”. So one can venture a claim that the positive dimension of the term “nation” was enhanced when the Enlightenment patriotism of educated elites took the floor, finding its expression especially in the idea of love for one’s homeland and countrymen exhibited in particular actions.

All this happened decades before the French Revolution, with which – as our textbooks would have it – glorifying of the nation began and started to spread all over Europe. I do not intend to question the significance of this revolution. Thanks to it the term “nation”, supported with the idea of civil society, gained a new content; for the nation should be formed by all citizens, equal before the law and acting in solidarity. And all of them were also to bear responsibility for spreading progress and the struggle for freedom in Europe. At this point one should also state the caveat that the term “nation” acquired its civic dimension earlier, but only thanks to the French Revolution did it assume a universal meaning. The Revolution, and to an even larger extent the Napoleonic period in the history of the grande nation, turned the construct of a nation into an individualised, intellectualised and ideological term, and it became a kind of “mandatory” common good.

Therefore, when looking for the origins of the emotionalisation and glorification of the concept of a “nation”, practically until today identified with a later period, we find ourselves in the times preceding the appearance of Romanticism by at least one generation. And it is this period which is sometimes held “responsible” for idealising the nation and for national enthusiasm. I believe this view to be mistaken. Of course, the Romantics – or at least some of them – took up the national idea and cultivated it, but they did not “discover” it and were not its authors. I suppose that such emotions connected both with the nation and the romantic stance are derived from the same or closely related roots. It was the deepening uncertainty of an individual faced with collapsing values and identity of the old society, the fading ancien régime. This uncertainty generated the need to discover new values and a new belonging. Of course, not all Romantics discovered this new centrum securitatis in the national community, and not all patriots became Romantics. By the way, it could be interesting and inspiring to find out to what extent the idea of national identity was a part of the idea of Romanticism and how many Romantics were active in the national movements in particular European countries. But a weak point of such an undertaking would be the rather big differences in defining the term “Romanticism”.

Regardless of the above, there is no doubt that in the 19th century the term “nation” was already a commonly accepted value. The existence of the nation and belonging to it were associated with something honourable and prestigious, but also imposing certain obligations on all its members. The national idea was carefully cultivated by the emerging nations in Germany, Bohemia, Norway and Hungary.

As the existence of the nation contained the aspect of magnificence, not every group could freely use this dignified name. Magnificence, like nobility in aristocratic families, obliged the nation to prove its historical origins.

In accordance with the spirit of historicism, popular in the 19th century, the nation was understood as a historical (that is, to use a current term, “perennialist”) phenomenon, the existence of which could be traced back to the Middle Ages. And as in the 19th century only political history was regarded as a true science of history, it was obvious that aspirations to being a nation not grounded in political history did not make any sense. In the revolutionary year 1848 the distinction between “historical” and “non-historical” nations became a subject of heated political discussions in Central Europe, provoked especially by German liberals.

This all meant that historically proven statehood traceable to the Middle Ages was regarded as a necessary condition for accepting a given group as a nation. Interruptions or periods of shaky statehood were tolerated. But there was no rule saying for how long and to what extent the statehood could have been interrupted. And it is not known whether an autonomous status, concerning, for example, Catalonia, was acknowledged as a valid substitute for statehood.

Simultaneously and in a growing opposition to this traditional distinction, its meaning was brought up-to-date, in the domain of associations assigned to the word “nation”. One could “awaken” a nation defined by its language and culture and announce its existence regardless of whether it could claim medieval statehood. Rather than solving the problem, however, this moved it to another sphere: since historical statehood was not decisive for acknowledging the existence of a nation, what features should have been “possessed” by a community wanting to be recognised as a nation?

The question of what a nation is and what it is not became the subject of study for positivist science, which attempted to define objective criteria. This process occurred in an aura of scholastic “realism”: it was believed that nations had a real existence and that there were “true” nations, which only had to be scientifically defined.

This belief received the first blow from the subjectivist definition of a nation, speaking about the national awareness of its members. This position was represented not only by the often quoted Ernest Renan but also by the theoretically inclined German statisticians from this period, who were longing for immutable criteria of national belonging. Another blow, unfortunately almost forgotten today, came in the early 20th century from the leading Marxist Otto Bauer, who claimed that one should distinguish many stages of historical development and, accordingly, many types of nation, from the nation of the gentry through the nation of burghers and intellectuals to the nation of the capitalist period. And Bauer was not alone in his views: in 1907, when his book about the national question appeared, the German historian Friedrich Meinecke proposed a division of nations into two types: state nation and cultural nation.

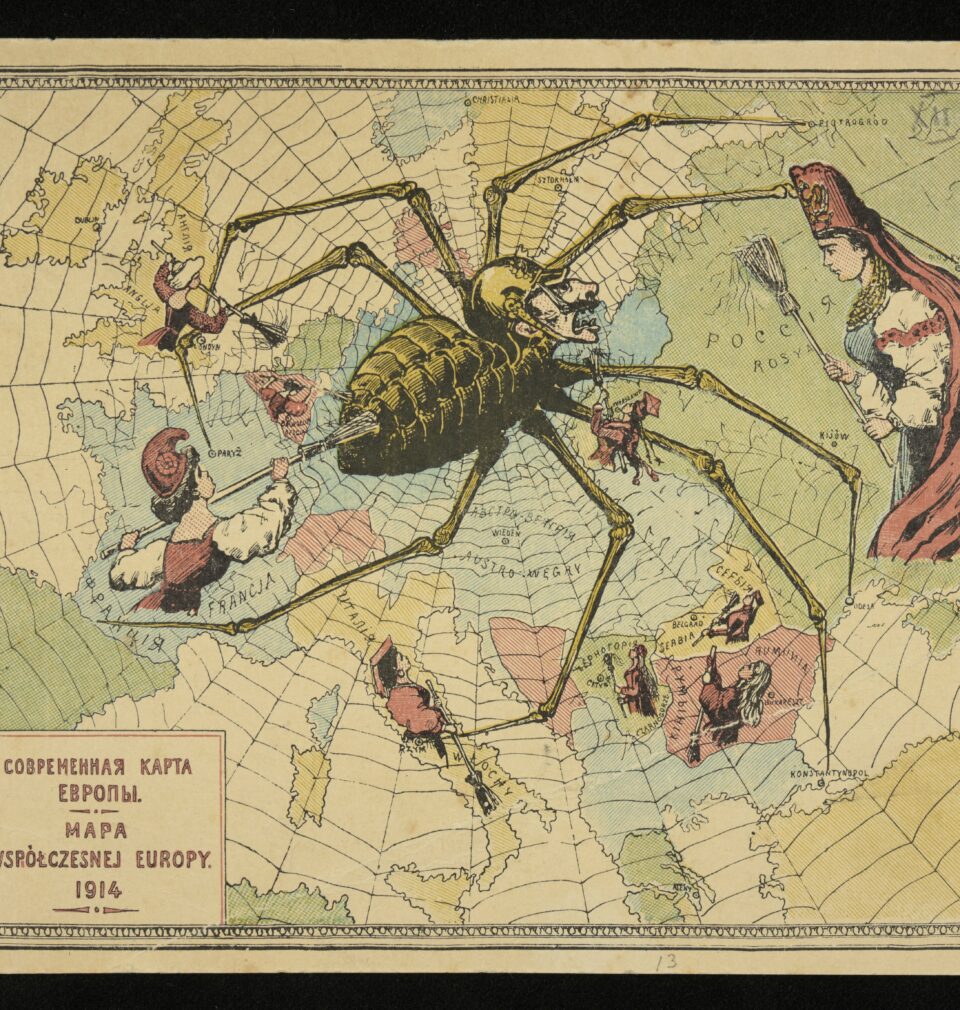

The turn of the 20th century saw the most intense debates on the definition of a nation, with a new term of political (but not yet scientific) discourse entering the stage: nationalism. This was a word without a past, a neologism with emotional overtones. For some, nationalism was a synonym for love of one’s nation (for example in France), which meant that it provoked positive feelings, while for others (especially for social democrats and pacifists) it posed a threat to humanity. The second definition was in a way confirmed by atrocities during the First World War perpetrated on behalf of the nation.

The various interpretations of this term notwithstanding, it is understandable that with the growing popularity of the subjective definition of the nation the term “nationalism” also successfully invaded the language of scholarship, beginning with the USA. This process, which in the United States began as early as the 1930s, supported especially by Hans Kohns’s “idea of nationalism”, was after the Second World War also adopted in continental Europe, first in social sciences and from the 1960s in historical research as well. Of course, this term, despite the reiterated claims that it was a “value-free” concept, was variously interpreted in particular languages, in line with associations provoked by the word “nation”. In some languages it really was free of negative overtones, while in others it had a strongly pejorative ring to it. In my view the aspiration to a universal use of this term is a “cuckoo’s egg” dropped by American scholarship into the European nest.

The term has gained an independent existence and, what’s more, the phenomenon it describes dates back to the 19th century, when the word did not yet even exist! Everything that concerned the “nation” was described as “nationalism”, usually without any distinctions, at best with a qualifier making its meaning more precise. Some authors (for example, Eli Kedouri or Ernest Gellner) saw nationalism as the moving force of the nation. But although nationalism was perceived as primus movens, prime mover, it was supposed to be causally explainable. There are few equally striking examples of a word or term becoming independent of reality and retroactively defining – or in a sense even “raping” – reality in an authoritarian way.

I do not intend to argue here with the thoughtless use of the term “nationalism”. Suffice it to say that most authors subsume under this term all opinions, actions and institutions which are connected with the nation or declare an intent at such a connotation. However, it remains an open question what should be understood by the term “nation”.

I am glad that in recent years more and more authors are refraining from using the concept of nationalism as a scholarly instrument, preferring such alternative descriptions as patriotism, national identity, awareness or belonging. I myself belong to the minority of researchers who understand the term “nationalism” in its narrower, negative sense – namely as a hateful national egoism, putting one’s own nation above others, mixed with xenophobia and chauvinism. In such a context the dividing line between negatively understood nationalism and national identity or patriotism is blurred; in other words, nationalism is constantly present and in some historical circumstances its voice may prove dominant.

The European nation emerged without “nationalism”

Let us now leave the sphere of words and turn to social and cultural reality.

The departure point for my reflections is the following, empirically provable fact: the majority of European communities describing themselves as “nations” adopted the form of civil society – to put the matter succinctly – in the period of modernisation. The modern capitalist society emerging at the time had to undergo the process of restructuring.

I will propose here a certain thought experiment: let us imagine that, studying the reforms introduced in the modern times, describing the social turbulences and changes, we do not know the word “nation” (not to mention “nationalism”). I will present a number of social and cultural transformation processes in such a way as if no general term covered them.

In early modern history, roughly between the mid-17th century and the 19th century, in all regions of Eastern and Western Europe there was a process of gradual or violent collapse of the structures of the late feudal ancien régime: first, the traditional feudal bonds and relations were questioned or even broken. Second, the appearance of manufacture and industry undermined and redirected the structures of the traditional system of agricultural and guild production. The old feudal world of the inheritance system was shrinking, its rules were becoming less restrictive and the class barriers not so obstructive. Moreover, the religious legitimacy of privileged feudal authorities – and consequently also the traditional system of values – was increasingly questioned. More and more people transcended the old patriarchal world, to which the generations of their immediate ancestors still belonged: this process was driven, on the one hand, by people looking for work outside their home place, and on the other hand by expanded access to university education. The idea of equality of all people before the law and state institutions was also gaining ground.

These processes occurred non-synchronically, that is in different periods in particular countries. They resulted in an identity crisis, a sense of uncertainty and their concomitants, initially appearing above all among educated persons: looking for new dogmas and forms of belonging as well as a new system of humane values.

An effect of discouragement connected with the growing inefficiency or even impossibility of identifying with the traditional rural or urban community, of questioning the monarchy and religious legitimacy of privileges, was the issue of the place of the individual in this “disenchanted world”. The withering of the principle deriving class inequalities from origin brought about a process whereby people sooner or later ceased to be subjects in a hierarchically structured world and became equal members of a civil society based on division of labour. With increasing social mobility and ever more powerful administration and bureaucracy the role of social communication was also growing; it went far beyond the framework of traditional rural and urban communities. At the same time, daily experience showed that communication was much easier with people using a tongue akin to the native dialect, that is using – depending on the social status – a similar spoken or written language.

This was an instructive experience, for thanks to participation in an education system developing at varying rates of vigour people were capable of imagining a community possessing certain common features – subject to one ruler, inhabiting the same historical land and having the same past or using a language or dialect comprehensible to its members.

This generated, or rather activated – first in the minds of the educated minority – the belief that the relations and bonds characteristic of the old society would gradually vanish. They perceived this vanishing as a restructuring or disintegration of class society into a community based on the division of labour, with all members having the same rights, understanding each other better, sharing the same fate, having the same interests and being capable of acting in solidarity.

This vision was based on the pre-existing – since the Enlightenment – idea of homeland, the good of which every educated man was obliged to serve – it was the Enlightenment concept of patriotism described previously. This idea found various political expressions: either as constitutional monarchy, often characterised by the notion of social justice strongly imbued religiously, or as a constitutional state built on revolutionary foundations, that is a republic.

So the forms varied but there was no alternative to the new structures of the social order and the cultural transformations of society. In other words, the only way of structuring modern society known to us is the version based on elements referred to as “national”.

It is only now, then, that we reach for this basic term usually mentioned at the start: “nation”. As I have said, this term functioned in all literary languages from that time and had positive connotations, although it was used in various meanings: referring to the homeland or political regime, in the context of independence, feudal privileges, individual freedom or defence from external threat. In several languages an alternative term existed – for example the “people” in German, also understood as a positive value.

Initially, therefore, the nation was not a previously prepared programme or project according to which society was to be reorganised, but the term perfectly described the new social and cultural reality, which – regardless of definitions – emerged from social reorganisation and was named the “nation”. This is not to deny the fact that in the 19th century a cultural transfer also occurred, when with some delay new national movements started to form, adopting (or intending to adopt) an existing nation as a model. Not only in Central Europe but also in Catalonia – slightly later, that is around 1900 – one could observe a move from the term “regionals” to “nationals”. In some European languages there was no abstract noun describing the nation, so appropriate new words were created (for example, kansa in Finnish).

What was the aim of this strange thought experiment? First, it served to illustrate in a more comprehensible way that the emergence of European nations was shaped by factors also clearly present in other parts of the world.

Second, I wanted to explain that in the process described as the forming of the modern nation neither the idea of its creation nor the idea of nationalism played the role of the so-called primus movens. Nevertheless, in later times the nation became a cultural and even ethical value in itself, a mandatory principle of life in solidarity.

The foundations for this situation had in a sense been programmed by the Enlightenment idea of patriotism. A patriotic representative of the Enlightenment considered it his duty to serve the people living in his homeland, although this was not tantamount to identifying with these people. It is a different matter with a modern patriot, who identifies with “his” people. This ethical redirecting found its reflection in the definition of a nation. The patriotically minded class of educated people regarded it as obvious that a helpful means of overcoming the identity crisis would be the use of the term “national”, defining the new identity from that moment on.

So far, this discussion has been taking place in perhaps excessively abstract terms, and it is high time to find out to what extent this theory squares with empirical, historical reality. First I will repeat that nation-forming processes not only were non-synchronic, that is occurred in various periods, but also possessed various social and political contents. The basic difference was that in a number of cases the modern nation was shaped through internal reorganisation of a state existing uninterruptedly for centuries, that is a state nation with its own ruling class, homogenous high culture and a written language, while in others this process was marked by a vision of a nation-to-be, to be realised through a national movement.

In order to base our reflections on specific examples of these two kinds of nation-forming processes, we have to imagine the map of Europe from the early 19th century. On the one hand we will find a limited number of states almost homogenous in ethnic terms: France, Holland, Portugal and Sweden, and two states with a dominant old state nation – Spain and Great Britain, countries inhabited by other ethnic groups besides the dominant one.

On the other hand we have the so-called ethnies (a term introduced by Anthony Smith), out of which in many cases independent nations emerged; most of them managed to form their own state. This process was neither historically “necessary” nor pre-programmed by “nationalisms”. In fact, not every group turned into a separate nation. This process ended in success in three multiethnic empires in Central and Eastern Europe as well as in the West (the Irish, the Catalonians, the Flemish, the Norwegians, the Basques). In these cases the path to a fully formed nation (even not possessing its own state) led through national movements.

It is not my aim to present the history of national movements in detail. I will limit myself to the remark that most of them sooner or later achieved their goal. The main issue was accepting the national identity by the people, which was supposed to help in shaping an autonomous culture, written language and a full social structure of the nation-to-be and to safeguard a certain degree of participation in administration and political decision-making.

Stateless nations emerged from the idea of the nation-to-be mostly in the second half of the 19th century. In their programmes they did not even raise the question of national independence, hoping only for achieving autonomy. In fact we know only a few national movements which managed to establish a state before the First World War. Almost in all cases these were countries located on the south-eastern fringes of Europe (Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria) as well as Norway, which became an independent state only in the early 20th century. To understand and interpret the specific stereotypes and political culture of the “small nations” we must remember this difference.

I will quote a few examples of such stereotypes: for members of small nations their national existence was (and still is) not an obvious fact – these nations repeatedly felt obliged to prove their aspirations to autonomy. For a long time after the success of national movements a stereotype of external threat to the nation and its interests dominated; in some cases this problem is still relevant. One can also notice the worship of simple folk as an authority or saviour of the nation, often accompanied by a liking for egalitarian democracy. Another stereotype is where a special role is assigned to education (of the people) perceived as an element of national identity. More frequently than in the case of state nations one can encounter here a kind of provincialism, understood as a deliberate isolation from the “grand world” and being satisfied with lesser ambitions in work and culture, coupled with a distrust towards all things foreign. Moreover, the formerly stateless nations did not and do not have any experiences as colonisers, and only a few Western European nations (the Scots, the Welsh, the Catalonians) took an active part in the colonial expansion of their state nations, profiting from it.

Concluding my reflections on the origin of the modern nation, I would like to warn against a certain wrong perspective which for me is a historical trap. The national present is very often seen from the perspective of 19th-century moral categories and vice versa: the past of nations and the behaviour of their members is often interpreted in line with today’s criteria. As a result many researchers, especially Anglo-Saxon ones, with blatant arrogance and using today’s criteria, appraise 19th-century national movements as “nationalist” or “ethnic” and transfer this judgement onto selected contemporary nations or national movements. Sometimes they are right, but usually they are mistaken.

What remains of the nation in Europe and in the world?

What is the condition of the nation in Europe and in the contemporary world? Although the national community was formed as one of the elements of modernity, it is fair to ask about its role or even legitimacy in the period of postmodernism. Has the nation fulfilled its social role, and is it therefore entering its twilight years? This is not a new question: as many as one hundred years ago such a prognosis was formulated by Rosa Luxemburg (and slightly less radically by Lenin).

I still remember genuine Leninists who attempted to predict when and how it would come to pass. Their only specific proposal was the discredited conception of the “Soviet people” – a supranation to which other nations would be subordinated.

One could draw a parallel between this conception and the contemporary phantasms of some Euro-enthusiasts, prophesying the downfall of the nation or the dissolution of “nationalism” in the common European identity. I will not analyse these predictions – if only because our everyday experiences belie them. But I would like to point to a certain misunderstanding resulting from the fact that too little attention is paid to the aforementioned difference between the emotionally coloured term “nation” and the rational, administrative or social and political reality of the nation state. By the way: what is the power of the emotional potential of European identity?

Considering the development of the “nation” from a macrohistorical and pan-European perspective, one can clearly see a certain significant difference between the 21st century and earlier times: currently the nation state is a European norm, an ordinary state of affairs. The 19th century left behind only a few stateless nations, almost all in Western Europe. Most European nations were formed without a state and in this shape they became elements of the European norm; moreover, by no means all representatives of their 19th century political elites longed for the establishment of their own state. But this is not the only difference present since the 19th century within the social group called the “nation”.

Comparing the communities which in the 19th century formed in large social groups called “nations” with the social reality currently described by this term and seen in the global context, we discover such large differences that a radical sceptic could claim that a “classic” nation (as a community) exists only in the form of traditional national institutions and as a memory that is constantly brought up-to-date. A thesis formulated in such a radical way is difficult to maintain, but I perceive in it a certain rational element. Let us therefore ask what remains from the bonds and values so significant for the European nation in the 19th century.

Currently, the nation is no longer perceived as a “value in itself”; instead, the importance of civil society (organised according to national and state rules) is underlined. We can also easily conclude that the emotional attractiveness of civil society is smaller than the power of the idea of national society in the 19th century.

In the context of the current neoliberal individualism the humanist imperative of serving humanity through serving the nation sounds alien.

The term “national interest” is most often used as a slogan in political agitation, and it is above all the interests of the citizens which can count on acceptance and support.

The words about the national interest sound serious only in the context of competitiveness of a given country in trade and industry, while the classic optimism connected with the idea of progress of a nationally organised society is perceived with disapproval or, at best, is questioned.

The majority of national codes, based on common historical tradition, have lost their validity: historical awareness is usually limited to contemporary history, utilised as an instrument of political struggle.

The common features of high and folk cultures (characteristic of the “classic” period of nations), on which the cultural national codes were based, no longer exist: the distance between high culture of the narrow intellectual elite and the strongly globalised (that is non-national) culture passed on by the media is growing ever faster. This medially globalised (and Americanised) culture is gradually replacing or marginalising national cultures.

In this context, the national language is also losing in importance, descending from the highest realms of national values and symbols.

These deficits are partly compensated for by a new force – unknown in the 19th century – reinforcing the sense of identity: this is sport as mass entertainment.

An important factor weakening national feelings is the pluralisation of identity. While previously national identity was regarded as an all-encompassing and mandatory form of belonging, today we know – and we use this knowledge – that every individual has many identities and that one can even claim two or more national identities. This leads to a weakening or obfuscation of the once clear dividing line between US and THEM.

Also important to remember is the difference resulting from facilitated horizontal mobility: we now observe a process of emergence of supranational elites, which do have a national belonging but ignore it. These elites can find jobs and earnings in any place in Europe and the world, and their language of communication is not their native language but the lingua franca, that is English.

The obviousness of national existence for almost all European nation states does not exclude relics and modified manifestations of national identity.

Among the positive relics, I include above all the demonstrations of national solidarity, important for society, occurring in crisis situations or during natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes.

Sudden explosions of nationalism in some post-communist countries have been regarded as negative relics. I will limit myself here to a short comment. These explosions are brief repetitions of national movements, occurring in conditions analogous to those which I described as a “classic” situation of identity crisis. This time the process happened in the conditions of highly developed social communication and fervent political struggle. The ethnic element was formulated largely in negative terms: as a rejection of the communist dictatorship.

A much more widespread, negative and permanent component is the growing xenophobia, directed at such “others” as immigrants – often manifested in a derivative form of a colonial-nationalist arrogance, but usually just a primitive reaction to the new phenomenon of multiculturalism.

Let us now turn to the global impact of the discussed concepts. In the second half of the 20th century the terms “nation” and “nationalism” spread all over the world, and today they have a life of their own. New states on the territories of former colonies adopted the name “nation”. Soon afterwards, or even simultaneously, a growing number of tribes or ethnic groups expressed an ambition to be recognised as a nation.

Some Asian and Latin American countries proclaimed themselves “nations” even earlier, during modernisation and in the initial stages of capitalism. Although an analogy with Europe could have been drawn on the basis of facts regarding the modernisation itself, the social, cultural and political circumstances as well as the beginnings of the process were completely different. Political scientists and sociologists did not hesitate to label these events as “nationalism”, usually without noticing that their classifications are completely divorced from reality.

In other words, the thoughtless use of the term “nationalism” opened the door in research – and perhaps also in politics – to a series of misunderstandings and false interpretations, emerging from naïve confusing of social formations which are completely different culturally (but bear the same name). The indigenous European term “nation” was imported (together with “nationalism”) to non-European countries only because they referred to themselves with that label. This process was usually accompanied by positive associations of the term “nationalism” – this was about a struggle against colonial exploitation by external actors and overcoming internal oppression.

Of course, one cannot halt the process (and the excesses coming with it) of cultural transfer, but we may fairly expect independent scientists to account in their analysis for the fact that historical conditions, traditions and social-cultural roots of global “nationalism” make it significantly different from the process which produced the European nations.

Concluding my reflections, I will sum up this confusing of concepts as a “global trap”. What does this trap consist of? It is generally assumed that the majority of the first freedom fighters, representatives of new African and Asian (and partly also Latin American) nations, used national ideas not so much to achieve internal cultural integration of state communities but to boost their own power and sometimes also to enrich themselves. Describing these events as “nationalism” does not seemingly come into conflict with assigning this model to the same category as the European nationalism and with using it in reference to the past, for “nationalism” had existed earlier and everywhere.

On the basis of the general premises, some recognised theoreticians have claimed that nations – regardless of the place and time of their emergence – are just constructs or even inventions of frustrated intellectuals or power-crazed politicians. Perhaps these theories are justified in the case of Africa or Asia, but they are clearly contradicted by our empirical knowledge about the history of European nation-building processes.

These divergences – and I return here to my point of departure – remind us of the methodical threat of divorcing concepts from reality mentioned earlier. The result of this divorce is that depending on the social and cultural conditions the same word describes completely different segments of society or political types of organised communities. What in the early 20th century was called nation in Europe now exists rather as historical background and reminiscences, and what is currently labelled as nation outside Europe is a completely different social and cultural community from the former (preserved to our times only as relics) European nation. And the word “nationalism” functions as a desired sobriquet – although usually concealing negative associations – which can be attached to any entity.

Nevertheless, the study of the tension between the concept imported from Europe and the African or Asian reality is a fascinating task for future scholarship.

In conclusion, we should emphasise that regardless of the specific and autonomous existence of non-European nations, the institutionalised reality of the nation is also undergoing significant changes in its European homeland. The process of emergence of nation states turned national existence into state existence, as a result of which national ideas became an object of political struggles, manipulated and controlled by politics. In short, we often get the impression that the national community, for which an individual was ready to fight and make sacrifices and which he regarded as centrum securitas, is gradually losing its original function. It has not died or vanished, but it lost its humanistic legacy and it still exists in the form of the state as a framework for the actual social community, but it is to a growing extent transferred into the sphere of words and rhetoric as a pretext for political struggle. It opens the door for demagogues and may be exploited by the media.

So the answer to the question from the title of this text, namely if today’s Europe needs nations, will be sceptical, or at least ambiguous. Yes, Europe does need nations; we need the principle of responsibility for supraindividual community, reflexive solidarity with the national collective, cultivating national cultures and the belief that constructive work serves not only the nation but also entire humanity. But such a concept of the nation does not exist any more and, if it does, then only as a memory, (old-fashioned) memento, lieux de mémoire. The nation survived to the present on innumerable stages where political struggles are played out, driven by individual or party interests, but the impact of supranational processes is increasingly pushing the national idea to the sidelines. I would venture a claim that this kind of nation is of not much use for future Europe.

Unfortunately I cannot conceive of a positive solution to this situation on the level of reality. But in the sphere of concepts, evoking the original humanistic nation-building ideals could introduce the distinction between egoistic nationalism and positive patriotism as an instrument of civic education.

Copyright © Herito 2020