Nations - History and Memory

It’s High Time Poland Recalled the Work of Moses Worobiejczyk

Publication: 13 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

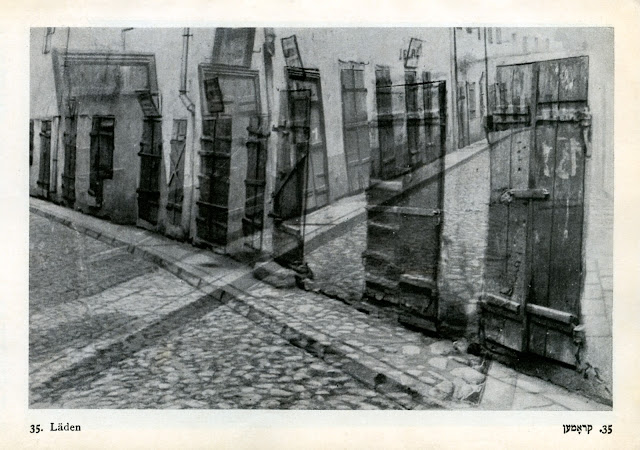

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESEin Ghetto im Osten – Wilna (A Ghetto in the East – Vilnius) is a unique book. This compact volume (19x13cm) contains 65 illustrations by Moses Worobiejczyk depicting the Jewish quarter in Vilnius.

The book is bilingual, with texts in German and Yiddish. It can be read or looked at from right to left and vice-versa. The mentioned illustrations are photographs or simple photomontages based on photographs taken in spring 1929. This little album was published in 1931 by the Swiss-German publishing house Orell Füssli Verlag, in a popular and high volume series denoted by the letters SB (Schaubücher). Worobiejczyk’s little book also had an English-Hebrew version, and after the Second World War there were a number of re-prints.

Interestingly, Moses Worobiejczyk and his work are not particularly well known in Poland. Worobiejczyk is mentioned in the essay Historia fotografii polskiej do roku 1990 (The history of Polish photography up until 1990) by Krzysztof Jurecki, which can be viewed on www.culture.pl, and in Janina Struk’s book Holocaust w fotografiach (Photographs of the Holocaust), but information about him is limited to the following: “Portraits of Polish Jews are shown in the photographs of Roman Vishniac from Warsaw from the late 1930s and Moses Worobiejczyk from Vilnius,” (Jurecki), as well as, “Józef Kiełsznia from Lublin and Moses Worobiejczyk from Vilnius documented the life of the Jewish community in their towns,” (Struk). A couple of facts need to be immediately corrected: Kiełsznia’s first name was Stefan, not Józef, and he was not involved in documenting “the life of the Jewish community in his town” in the slightest. Janina Struk gives the source of this information to be an album issued in 1991: 150 lat fotografii polskiej (150 years of Polish photography), compiled by the former editors of the quarterly Fotografia (which had closed down by that time). It was on the pages of this journal, in issues no. 3–4 (49–50), 1988, that the most comprehensive article so far about Worobiejczyk appeared, written by Jerzy Tomaszewski.

In the article, entitled Mojżesz Worobiejczyk, zapomniana karta historii fotografii (Moses Worobiejczyk, a forgotten page in the history of photography), Tomaszewski provides extensive information about the author of Ein Ghetto in Osten – Wilna, accompanied by illustrations consisting of a few photocopied pages from the Vilnius album. Nowadays, the biographical data contained therein can be found on the internet; however, it should be remembered that the mentioned text was written about eight years before the internet became widely available. In spite of the greater availability and speed of the internet, not much has changed in this matter; 24 years after publishing the article in Fotografia, knowledge of Worobiejczyk’s achievements in Poland is still at the same level, ie almost nothing. However, there were some things which happened during these years: in 2004 Steidl Publishing House re-issued Worobiejczyk’s second album, Paris, a book which was first published in 1931, bearing a foreword by… Fernand Léger. The re-edition is titled Ci-Contre – 110 Photos by Moï Ver, and the photographs from the book (more accurately: photomontages) were exhibited in winter 2004/2005 in Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich.

But let’s start from the beginning. Moses Worobiejczyk was born a subject of the Tsar in 1904 in the village of Lebedevo in Lithuania. He spent his childhood in Vilnius where he attended a “Tarbut” school, with Hebrew as the language of instruction. In 1924, as a citizen of the Second Republic, he began studies at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Stefan Batory. He continued his education between 1927 to 1928 at Bauhaus, and then for the next two years in the Parisian École de Photo et Cine. In 1927, together with Salomon Białogórski and Benzion Michton, he took part in an exhibition featuring young Vilnius painters, Fun Szul-Hojf bis Glazer-gas (From the Synagogue Courtyard to Szklana Street), which researchers of Yiddish culture consider to be a direct precursor of the formation of the literary-artistic group Jung Wilne. In May 1929, during an exhibition of paintings, graphic art, sculpture, and photographs of young Jewish artists of Vilnius, he displayed his photomontages. These works, later exhibited in Zurich during the 16th Zionist Congress, aroused considerable interest and bore fruit in the form of contact with the Orell Füssli Verlag Publishing House, which in 1931 published the little album Ein Ghetto im Osten – Wilna. The above mentioned book about Paris was also published at the same time. In 1932, Worobiejczyk, as a photo-reporter for the weekly Vie, was sent to Palestine, where he finally settled down for good two years later.

A certain S. Chnéour (the author of the foreword entitled Die Judengasse in Licht Und Shatten, A Jewish street in light and shadows), who is visible on the front cover of the Vilnius album, is actually none other than Zalman Shneur, the eminent and then well-known poet and novelist, who wrote in Hebrew and Yiddish. Choosing him was not only a great marketing move – at that time he wrote popular stories for the New York daily Forverts (which was published in Yiddish and had a circulation larger than the New Yorker) – but was also probably motivated by the fact that Shneur, who was 20 years older than Worobiejczyk, had lived in Vilnius between 1904 to 1906 and was the author of a Hebrew poem about the town. But his somewhat grandiloquent foreword (today we could say that in places it is unbearably “poetic”), in which he compares the streets and alleys around the Great Synagogue to… a “fortress”, and the inhabitants to “soldiers from the front line”, didn’t arouse the enthusiasm of reviewers. Actually, strictly speaking, we should use the singular here, reviewer, because a review of Worobiejczyk’s little album did indeed appear just after its publication, except that it was in… New York, on the pages of the above mentioned Forverts.

Its author, Max Weinreich, who was the founder of the Vilnius branch of the Żydowski Instytut Naukowy (YIVO – Jewish Scientific Institute), astutely observed that the desire of the residents of the area shown in the book was rather to leave behind all these “shadows” and move out of the slums into (literally) “the sunlight”. This was how he understood the material prepared by Worobiejczyk and at the same time noticed that the author of Ein Ghetto im Osten – Wilna missed out a lot of the more modern aspects of “Jewish life” (“why are there no Jewish workers’ demonstrations”?), which were also typical of this quarter, which was perhaps linked with his fear that such a mixture of “old” and “new” might not appeal to the imagination of the publisher. This somewhat stereotypical look, so accurately perceived by Weinreich, is most noticeable in the case of portrait photographs or photographs showing passers-by on the street, where the method of presentation of models and their selection could sometimes paradoxically resemble the propaganda publications, posters or anti-Jewish films that appeared a few years later…

The artist himself must have eventually become aware of this, since in 1945 in Tel Aviv he decided on a renewed publication of photographs from material recorded before the war in Vilnius (a portfolio of 10 photogravures entitled Polin). His photographs appeared in a very pure form and bore a greater resemblance to the “humanistic” photographs of Roman Vishniac from the book Polish Jews. A Pictorial Record (published in New York in 1947) than those from the schaubuch published by Orell Füssli Verlag. Interestingly, both Worobiejczyk’s photogravures, which were his artistic reaction to the increasingly grim news concerning the Holocaust (which reached Palestine, where he lived, towards the end of the war) and Vishniac’s American album, at that time met with complete disinterest on the part of the broader public. The portfolio of ten photogravures, Polin, is currently an antiquarian rarity. Photos by Roman Vishniac commissioned between 1935 to 1938 by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Poland, Czech, Hungary and Romania, only became known and popular after their publication in the album A Vanished World in 1983 (the same photograph was used on its front cover as on that of the 1947 book).

In the previously mentioned article about Worobiejczyk in Fotografia, Jerzy Tomaszewski wrote thus about the Vilnius album: “The photographs (…) drew the reader’s attention by their ability to reveal the atmosphere of the old streets in which Jews had worked, studied and prayed for generations. The composition of some photographs may suggest the influence of Bułhak, who at the time reigned supreme in Vilnius photography circles. However, Worobiejczyk went further: he opposed the grand master, showed details of dilapidated architecture and muddy streets and, above all, created montages of various shots. The impression was enhanced by his original juxtaposition of fragments of architecture and human figures, rarely applied viewpoints, unexpected formats and the shapes of the photographs themselves. Painting studies probably helped the artist to go beyond traditional photographic approaches. The mood of the photographs is often reminiscent of Marc Chagall’s paintings, showing a townscape of the Jewish streets of Vitebsk and other small towns, full of poetry.”

Since Zalman Shneur also mentions Chagall in his preface, the matter should be treated seriously, but there’s a million dollars to anyone who can see a visual analogy with the author of Lovers over the Town! Perhaps if we are talking about using motifs from the native landscape and changing them into “art”. If we want to look for some painting analogies with Worobiejczyk’s Vilnius, then perhaps they can be found, but rather in the work of Chagall’s teacher, Yehuda Pen (although with considerable reservations). Jerzy Tomaszewski also quite inaccurately draws parallels with the “grand master” Jan Bułhak; for Worobiejczyk, however, his photographs weren’t (and it is rather difficult to believe they ever were) any sort of a reference point. Looking at the layout of the photographs and photomontages in the Vilnius album, we see here rather the effects of education at the Parisian École de Photo et Cine, studies at the Bauhaus under the guidance of Josef Albers, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, and finally constructivist photomontage reading.

Similarly to contemporary silent documentary film makers, in the visual narrative constructed by him (the photographs in the album have been systematically arranged in the form of a “film”, which, additionally, can be viewed in two directions), Worobiejczyk often changes the method of image cropping, uses techniques such as foreshortening and “dissolve”, and concentrates photomontages. All of these measures, which serve to enhance the expression of the image and suggest “meaning”, turn out excellently when applied to mass open air demonstrations, urban traffic or building sites bristling with cranes, but do not always work well in the case of a difficult theme such as a neglected and claustrophobic district of a provincial town. When we look, however, at the fourth page of the book (which is the “title” page for readers of Worobiejczyk’s book in Yiddish or Hebrew), where we have a photomontage made up of multiple images of locked and bolted shops fronts, we see a fascinating image made up of “quotations of reality”, which may conjure up associations with photographs from… the pop art genre three decades later.

There are more photographs or rather photomontages of a similar character in the little album. In the case of the work entitled Läden (Shops), we are dealing with a classical “photographic sandwich”, in other words putting together two negatives and copying them together. A great photomontage on the next page entitled Ein Erwartung des Käufers (Waiting for a client), is a mosaic image, created from a fragment of a shop window with the owner sitting in the doorway, previously duplicated in various sizes and shades of grey. Looking at these purely graphical solutions, we may wonder about the sense of placing such (sophisticated) illustrations in a popular schaubuch (which is something of “mystery” to the author of this article). When we look at other books (where illustrations also play a key role) released onto the publishing market by Orell Füssli Verlag at around the time of Ein Ghetto im Osten – Wilna, then apart from the usually innovative layout of these publications, the photographs themselves are not especially extravagant. The Vilnius photographs of Moses Worobiejczyk, just like the work of the earlier mentioned Roman Vishniac, may also be appreciated without paying attention to the aesthetic motifs. Because whether we consider the composition of these photographs as being influenced by avant-garde cinema, constructivist poster or the “visual humanism” of black-and-white photography, they are an unchallengeable documentary record of the appearance of people (and also places in which they were photographed) who were later killed during the realisation of the Endlösung der Judenfrage.

“It is high time to recall the work of Moshe Raviv – Moses Worobiejczyk – in Poland as well, to which he is linked by memory and sentiment,” wrote Jerzy Tomaszewski in Fotografia in 1988, having somewhat earlier had an opportunity to visit the artist, who was then living in the town of Cfat in Israel. Moshe Raviv (for that was the name adopted by Worobiejczyk after the establishment of the Land of Israel) died in 1995, which was not noted by Polish cultural periodicals; the same was true in the case of the re-issue of the album about Paris and the exhibition at the Munich Pinakothek der Moderne. It is indeed high time (to repeat Jerzy Tomaszewski’s words) for Worobiejczyk to at last feature in histories of Polish photography as an original and creative photographer, and not just the author of “portraits of Polish Jews” or as a person who “documented the Jewish community in his town”. It is high time for a comprehensive and richly illustrated monograph, which will take into account not only the album which has been broadly discussed here: Ein Ghetto im Osten – Wilna, but also photos printed in newspapers from that period such as Dookoła świata. Such a monograph will encompass the album from Paris, will draw attention to the dozens of posters designed in Palestine and Eretz Yisrael after its establishment, will make available photographs from Polin and the second portfolio devoted to the city of Cfat (mentioned by Jerzy Tomaszewski) to a broader public, and finally will also present the paintings of Moshe Raviv, who finally broke with photography in the 1950s.

Translated from the Polish by George Lisowski

The author wishes to thank Karolina Szymaniak for making a copy of Moses Worobiejczyk’s album Ein Ghetto im Osten – Wilna available.

Copyright © Herito 2020