Croatia in Europe

The Future of the Past in Croatia

Publication: 14 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESEven though democratic Croatia was founded only 23 years ago, it is by no means easy to speak about its youth. This is a country that experienced both exhilaration and suffering at the time of its establishment. Therefore, we can speak of its inherent contradiction, because this child of Eastern Europe’s emancipations following the year 1989 had to endure tragic events which forced it to grow up quickly, which was not easy at all. In the early 1990s, many Croatian citizens feared for the lives of their loved ones, and the psychosis of war had many tempted to blame or hurt their closest neighbours.

In the 23 years since the introduction of democracy, Croatian citizens have been influenced by politically motivated emotions, sources of which can be found in the recent and distant past. Even though the year 1990, when the first democratic elections were held, can be viewed as a turning point, much like the fall of the Berlin Wall, the following questions can be posed: Where is the borderline between the “past” and the “present”? What makes up the national identity and is there any point in discussing it anymore? In the words of Norbert Huse, which are the “desirable” and which are the “inappropriate” monuments in Croatia after 1990? In the past several years, which can be termed the period of slow transitional aftermath of war, these questions have been voiced openly. They are challenging, because it is very difficult to give a general evaluation of a community, even if it is a relatively small one. The answers would presuppose the acceptance of Halbwachs’ belief that communities which share memories can be viewed as defined entities.

In Croatia, there is an interesting saying according to which two Croats will establish three political parties. The saying is instructive, and at the same time commendable and reproachful. But if memories are related to spaces – as we can read in Cicero and Frances Yates to Pierre Nora and Paul Ricoeur – then in grasping these polarisations, one should not ignore that the communities which have adopted the Croatian name are still disintegrated in their own country owing to a seemingly banal reason – geography. This fragmentation can be seen as the reason for the cultural diversity and richness, but it also represents an interpretative problem. Anyone taking a trip across Croatia (not just along the coast, which is the most interesting region for tourists), will be able to see an unusual diversity within a relatively small area. Thus, in Croatian history rivers served as boundaries of cultural and religious worlds, and the Velebit mountain range that extends from Rijeka to the hinterland of Zadar split dialects, climate and customs of coastal and continental Croatia. This was the reason why Ivan Kukuljević, a conservator in the mid-19th century, saw his projects of political unification and collecting historical documents as a task that needed to be carried out on both sides of the mythical mountain, celebrated in Croatian literature as early as the 16th century.

When it comes to the preservation of cultural memory and identity in the area of present day Croatia, it should be pointed out that from the times of the Renaissance these depended on the co-existence of an elite as well as a popular culture. I emphasise the word “co-existence” because the people, as well as church officials, have used the Glagolitic alphabet since the Medieval period, while Renaissance writers (for example, the “father of Croatian literature” Marko Marulić from Split) showed equal interest for ancient monuments that they interpreted in their Latin texts, and for the vernacular, in which they drew up their key works. With the advent of the Ottoman army they were imbued with an existential fear that they tried to suppress by the use of the vernacular in composing sayings, prayers and various poetic forms.

On the other hand, one of the constituent parts of the history of Croatian culture is the constant presence of foreigners, ranging from invaders to the learned. Croatian communities under the influence of Venice, Austria, Hungary and Turkey used different dialects, and after the 17th century they were viewed as a religiously and culturally homogenous space that had already acquired the name of Illyria. This common denominator for the heterogeneity of the later unified culture became a sort of nom de guerre used by Catholic scholars who dreamed of a reconquest with the help of Rome and of a new structure of the area. In the Romantic era it became a political instrument in the hands of antiquarians and politicians termed the Illyrian movement.

It should be noted that before the appearance of the first national museums in the age of Austrian Emperor Francis I and Chancellor Metternich, the national identity in Croatia was always based on the written tradition. In Croatia, the perception of visible and tangible objects that lost their practical but gained a commemorative value had already appeared in early humanism with the arrival of Italian antiquarian Cyriacus of Ancona. But before the 1830s the debate on epigraphy, numismatics, topography and archaeology dealt exclusively with the heritage of antiquity, which was accepted as having universal value. Neither Marulić in the early 16th century nor antiquarians in the 18th century felt the need to address anything but Roman antiquities in their visible cultural environment. When Kukuljević became the conservator of the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia, the term “monument” started to cover written documents and artefacts that began to be collected systematically.

This brief historical outline seems important for an attempt at interpreting another fact that marked the perception of history in modern Croatia. It concerns the effort to complete the 19th-century project of the Illyrian movement by projects of Croatian politicians after 1990. Like his European contemporaries, as the founder of the national art history and conservation tradition, Kukuljević saw clear political objectives in collecting and inventorying national treasures (from sayings and writings to moveable objects and architecture). However, one thing was specific to Croatia at the time – and this is largely the case even today – the latent neo-colonial mentality that was reflected in the lack of a significant number of freethinking and level-headed exponents of cultural initiatives.

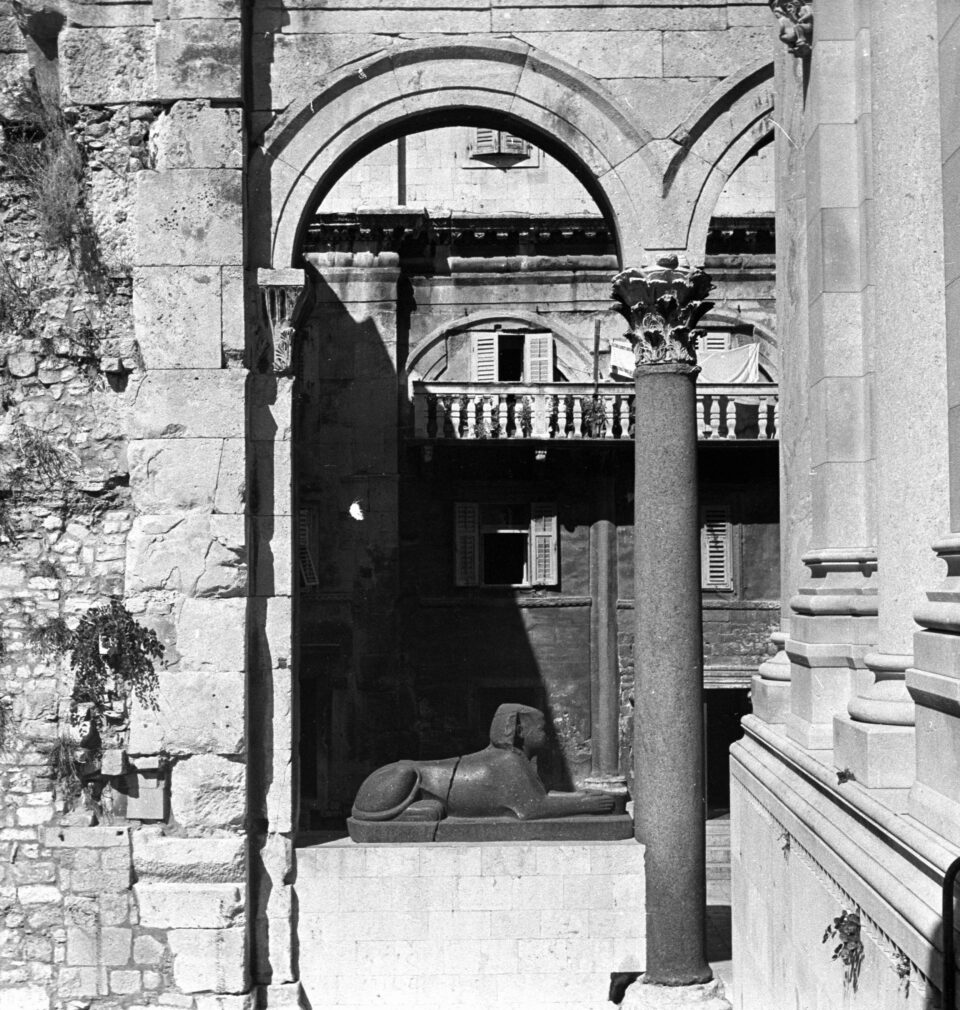

Kukuljević’s solitary position of an enthusiastic polymath in the Habsburg super-state who dreamed like Jàn Kollàr, Carlo Cattaneo or František Palacký of national particularity and emancipation, shows the specificity of Central European nations at that time. Unlike France, Prussia and England in those days, where champions of the culture of romanticism had already convinced the state and church officials to collect data about national monuments and by restoring them to transform them according to the current historical imagination, with some interruptions in the following decades in Croatia, individuals continued their work trying to convince statesmen and the people that cultural heritage was important, but were more or less unsuccessful. Nevertheless, in their historical and conservation canon, Croats, like Austrians, Italians, the French, the English, Czechs, Poles and Germans, have a gallery of men and women who served as intermediaries between the political elite and the masses. The generation of Alois Riegl, Max Dvořák, Camillo Boito, Gustavo Giovannoni, Paul Léon, William Morris, Georg Dehio and Cornelius Gurlitt around 1900 is matched by Gjuro Szabo, Emil Laszowski, Viktor Hoffiller and Josip Brunšmid in Croatia. They were not just passive recipients of the innovative conservation ideas of the European fin-de-siècle which promoted the expansion of the term heritage and the preservation of stylistic complexity in historical settings. Just before the start of the First World War, using the perception of monuments, they advocated tolerance, following the instructions of Riegl, to whom the notion of human was more important than the notion of national. Croatian experts, like Czech and Polish experts, had the good fortune to work directly with Austrian champions of the new conservation theory Riegl and Dvořák. An example of this work was the problem of the maintenance of Diocletian’s Palace in Split. Their ideas, along with those of the German theory guided by the motto konservieren, nicht restauriren, marked the work of Croatian conservators practically until the last quarter of the 20th century.

The triangular relationship that political authorities, scholars and the nation enter into and that developed as a form of social contract after the French Revolution, constantly experienced changes in the balance of power in Croatia in the burdened 20th century. Without undue generalisation, it can be said that after the fall of Austria in 1918, this relationship was under constant watch by the political elites. In the period before 1945, historians and conservators in Croatia worked within a poorly developed system of higher education and government departments in which identities were suppressed by police persecution, eradicated by policies of the regime and during the Holocaust, were constructed in a mythical narrative by the collaborators. In the socialist system, which boasted a revolutionary nature, there was an interesting blend of modernisation and the hitherto most ambitious construction of a system of cultural heritage preservation. While the national was supposed to be suppressed by the narrative of the supranational (or the Yugoslav version of the famous motto égalité–fraternité), the conservation system blossomed for the first time in the history of Croatia, combining the historical and topographical approaches to heritage with the restoration approach. Thus, along with the autopsy conducted by the newly established institutes, work was done on reconstructing the monuments of “non-popular” regimes, and so in the heavily bombarded Senj, the cathedral was reconstructed, and in Šibenik the Renaissance City Hall of Venetian administration. These interventions were carried out at the same time as the reconstruction of Polish cities, and they coincided with the persecution of the Church and the denigration of previous administrations in the official historiography.

Even though Croatian historians of preservation are yet to make greater discoveries about these times in the archives, in these systems one can recognise a situation that was known in Europe until 1789 – a lack of genuine public reception, as well as a lack of a constant public debate on the discovery of new values and the preservation of the existing ones. This was essentially the situation before the first multiparty elections in 1990. Experts were given their role within the structured political system, as well as social importance, but in a society where expressions of certain opinions were regarded as a legal offence, one could not talk about a free exchange of knowledge and the development of appreciation for different kinds of past. Furthermore, conservation successes were rarely or never given attention and importance in public the way this was done in Poland, Germany and Italy with experts such as Jan Zachwatowicz, Hans Döllgast and Alfredo Barbacci, to whom memorial plates were erected on the buildings they reconstructed and who were celebrated as healers of traumatised communities.

Changes in conservation paradigms promoted in Europe at the turn of the 20th century, which were stopped by wars and totalitarian regimes, were supposed to keep up with social and political changes in Europe after 1989. However, experiences varied. In Russia, in the words of Natalia Dushkina, the discovery of the suppressed heritage began with the “romantic” and soon entered the “barbaric” phase. The Resurrection of Lazarus – of images of monuments destroyed long ago, as a result of what Wolfgang Pehnt called “a yearning for history” – and at the same time a merciless destruction of religious and national treasures in the wars from the Caucasus to South-Eastern Europe, show that in the past 20 years the new societies redefined the understanding of what national heritage is. In Croatia, the establishment of the new state followed the rise of new historicism in which some wanted to merge the past with the present in an uncritical way. Linguistic archaisms, fabricated historical uniforms and the eclecticism of new state symbols were supposed to contribute to the value of novelties. But one of the main problems of this small country was in self-censorship of the citizens themselves, who had become so used to resisting the authority of the government to such an extent that they had become wary of sharing experiences in the perception of values. The education system of the period bears a large part of the responsibility, as it did not pose questions on spaces of memory nor did it analyse traumas from the past in a critical way, so the citizens were not provided with an incentive to create their own pride and social ethos, which should be reflected in the acceptance of the concept of altruism.

After large-scale destruction, ethnic divisions and tragic migration, in large parts of Croatia, visitors, as well as those same citizens from the beginning of the process of emancipation in 1990, may experience mixed emotions. While they may be amazed by the exquisitely preserved Dubrovnik, now jeopardised by modern development, they will be appalled by the desolated areas of Lika and Banovina. In post-war Croatia, the political discourse easily claimed victory over the professional and the public. Experts have been co-opted or pacified within new forms of the bureaucratic system, and the public was offered a non-scientific discourse about the past where until a decade ago the idea of the nation pushed aside all other forms of memory. Recently, a new narrative has been added to the decaying and politicised system, one about life-saving foreign investments, which has jeopardised a scientific overview of the past and the public perception of historical ambience much like in Italy of Salvatore Settis and Silvio Berlusconi.

Be all that as it may, Croatia, now on the threshold of the European Union, has a very noticeable and promising potential: the disgruntled, mostly young people who have started asking all these questions about the temporal boundaries between “us” and “them” and the point of making such boundaries. While the university circles discuss the ethics and impartiality of the historical discussion about the last century, and while an unnecessary decentralisation and insensitivity to the public interest can be felt in the 20 conservation departments established by the political principle of divide et impera, the number of NGOs is increasing in the country every day. Anyone who is at all familiar with the history of conservation will dare to assume that these new communities, which share “the yearning for history”, will mobilise the rest of the public and force it to change. So, even though not much is being done for the neglected national monuments or the cities which still bear the scars of war and to which no one can return with ease, at the same time Croatia is discovering new landscapes such as industrial heritage (in which this de-industrialised country is beginning to abound) and Austro-Hungarian army barracks and fortifications. In turn, students have launched projects of “city district museums” and tours of abandoned buildings of the army of the former Yugoslavia, commemorating the everyday modernist-socialist communities and re-examining the phenomenon of oblivion after social and ideological changes. These new and exciting landscapes and new value systems testify to the new perception promulgated by David Lowenthal, Salvador Muñoz Viñas and Marion Wohlleben. These new traditions should be embraced because the cult of monuments that is now evolving can help spread the sensibility in Croatian public, which needs a sober view of the past as much as it needs freedom.

Translated from the Croatian by Marko Majerović

Copyright © Herito 2020