Nations - History and Memory

History and Historical Policy

Publication: 14 October 2021

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESThe story of mythologizing the figure and the actions of Alexander Yaroslavich (and by no means just of him) reflects both the history and the very essence of the Russian system of power. Violent and cut off from its own nation in its aloofness, it created false idols for the people, so that by worshipping them, they worshipped the regime itself, blindly succumbed to its authority, obediently believing in its principles as the highest values.

“Russia’s past is beautiful,” claimed the dignitary closest to His Imperial Majesty Nicholas I, head of the gendarmerie Count Alexander von Benckendorf. “Its present is wonderful and its future transcends the human imagination. It is from this angle that Russian history should be described by a Russian.”

Such directives for historical policy issued by the Russian regime are absolutely clear and do not require a comment. (As the Reverend Benedykt Chmielowski said some three hundred years ago in Nowe Ateny [New Athens]: “What kind of animal the horse is, anyone can see.”) We can only admire those Russian historians (such as Vasily O. Klyuchevsky) who wrote history on the basis of sources rather than directives of official ideology. What keeps me from restraining from further reflection is the dictum of a Polish statesman: “Not every truth is educational. Sometimes you have to bite your tongue.”[1] But what are the results when professional ethos or simply defiance do not allow you to bite your tongue? Let the countrymen of Lech Wałęsa (for these are his words) judge for themselves.

For obvious reasons I am using only materials from Russian history and historical policy, but they illustrate not only the Russian situation.

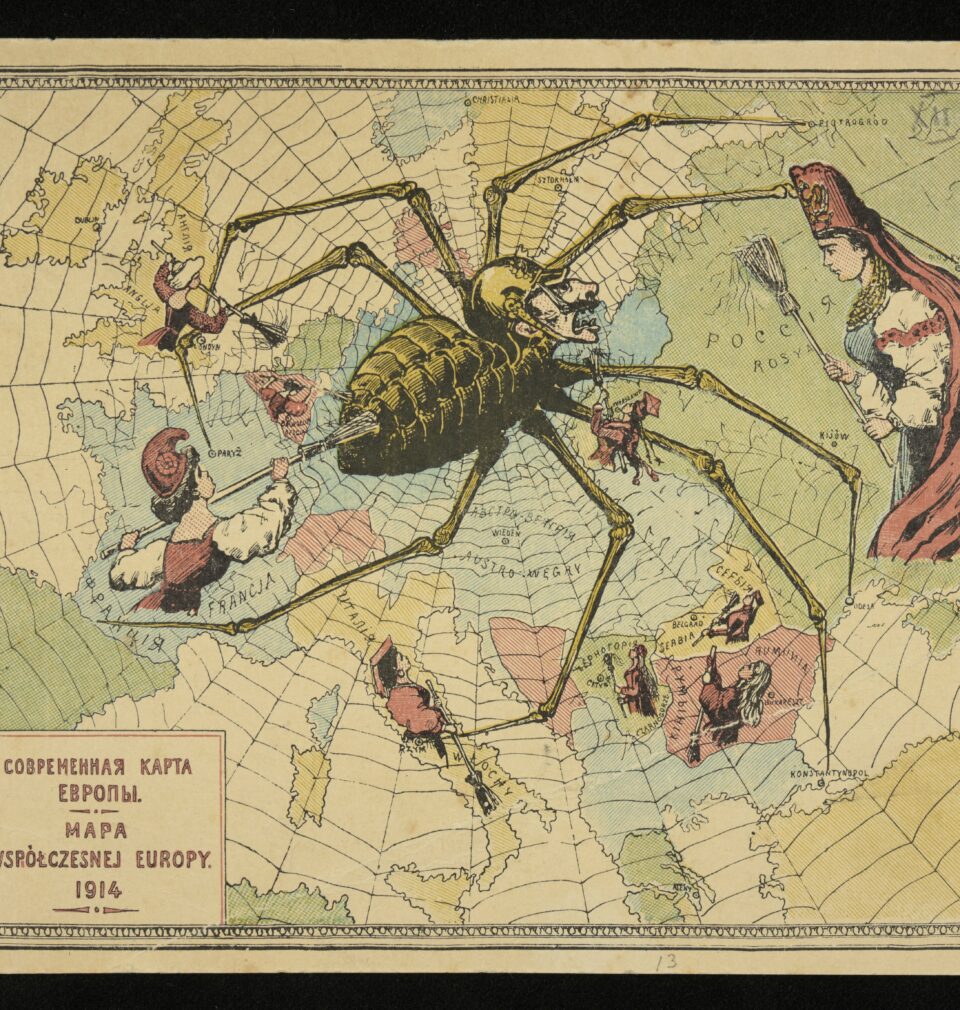

In the academic world and outside it there has been much talk about historical policy. A look at this issue from the perspective of the annals of interpreting history highlights the obvious fact that this new name in fact describes the age-old practice of utilising history in order to create the desired attitudes and views. This intent is quite understandable from the pragmatic point of view, but from the perspective of logic the very method of implementing it raises doubts, for in practice it is done on the basis not of history as such but of ideological visions or political doctrines which were deemed correct and useful in specific countries and specific periods. Therefore, in various national cultures the same history of native Europe (to use Czesław Miłosz’s phrase) is seen from various perspectives, from which different conclusions are drawn for successive national presents. And therefore within each national culture every successive reinterpretation of the history of a given nation serves at drawing currently needed conclusions, which shape new models for each successive present. This is illustrated by the case of Alexander Nevsky.

The prince’s rule according to history and the story of the worship of a saint and a role model of a national hero according to the “historical policy” of the Orthodox Church and the state.

The official picture of Russian history and the state-building Pantheon of its role models, reproduced until today, reaches back to the beginnings of the Russian autocracy. It has been consistently continued, deepened and brought up-to-date in the times of the St. Petersburg Empire, Soviet totalitarianism and the current Russian Federation. A telling example of such a sequence of finding and strengthening a virtual tradition is the story of the Novgorod Prince and since 1252 the Grand Prince of Moscow Alexander Yaroslavich (1220–1263), who was proclaimed saint by the Orthodox Church and made into a standard national hero by the state.

It was the same prince who after concluding a separatist peace with Batu-Khan no longer took part in the fight of Rus’ against the invader; having secured the backing of the Golden Horde, he fought against its foe, that is the West. Not only was he a loyal and devoted ally of the Mongols, but he also became the Khan’s relative. When Rus’ was shedding blood and losing sovereignty, Alexander and the Khan’s son Sartaq cut their hands and ritually mixed their blood, becoming brothers.

In the official history Alexander Yaroslavich consistently appears as Alexander Nevsky, for allegedly his contemporaries were the first to give him this sobriquet after the allegedly famous victory over the Swedes in the “grand battle” (1240) on the Neva River. In fact the First Novgorod Chronicle mentions this incident as a minor frontier skirmish, where twenty Novgorod warriors were killed and the Swedish detachment retreated across the river, where it was crushed by local Ugro-Finnish tribes allied with Novgorod. Scandinavian records completely omit this “world-historical battle”, while the Brief History of the USSR from Stalinist times says bombastically: “The victory of the Ruthenian nation under our great ancestor Alexander Nevsky as early as the 13th century prevented Rus’ from losing the Finnish Bay shore and a complete economic blockade.”[2] “The younger squad” (that is a subordinate part of the household troops of the Novgorod Prince) is identified here with the “Ruthenian nation”, a local leader with the leader of the whole Ruthenian army, which did not exist as such at that time, the lands of Ugro-Finnish tribes with the lands of the whole of Rus’, a frontier skirmish with a battlefield victory. As for preventing the “loss” of the shore, it is difficult to square this with the well-known subsequent Swedish expansion in this part of the Baltic and founding fortresses and fortified towns. (On the site of one of them – not in a wasteland, as the official history would have it – Peter I founded the capital of his empire.) The sobriquet “Nevsky” was assigned to Alexander Yaroslavich at least two and a half centuries later – in the late 15th century, when independence created the need for founding and state-building myths of Muscovy.

Also in later times and in a similar mode – on the wave of mythological needs and within the myth-making ideology – the importance of the victorious battle of the young Novgorod Prince with the Teutonic Knights in the winter of 1242 on the frozen Lake Peipus (Chudsko ozero) was exaggerated. We find no single word about this “decisive battle”, the “united forces” of Rus’, the victory saving the nations from “German slavery”[3], the threat of “Catholicising Rus’, its ultimate break-up, the loss of national independence”[4] in the Hypatian Codex; only later is there a short mention in the Lavrentyevsky Chronicle and just two sentences in the First Pskov Chronicle. And there is nothing strange in that if we consider the scale of threat posed by the Livonian and Teutonic Orders, with about one hundred knights between them. And the “united forces of Rus’” are just troops from Pskov and Novgorod, which – as we read in the Novgorod Chronicle – robbed the settlements of Baltic tribes (ancestors of Latvians and Estonians). It was on their native land (which was the bone of contention between the Pskov-Novgorod Rus’ and its Teutonic and Swedish neighbours) rather than Ruthenian land that the battle took place where the Balts and the Germans fought against the Ruthenian newcomers. (And it is not mentioned that Alexander fought arm in arm with the horsemen of Batu-Khan, with whom he had concluded a separatist peace, while other Ruthenian princes united against the Mongol invader). The Livonian Rhymed Chronicle from the late 13th century informs us that in this Battle of the Ice (hence the Ruthenian term Ledovoye poboish’ye, Ледовое побоище”), 20 knights were killed and six were taken prisoner. And the First Novgorod Chronicle says that “countless Chudi [Balts – A.L.] were killed, Germans four hundred, while fifty were taken prisoner and brought to Novgorod.”[5] (It is assumed that the author of the Chronicle gives the overall number of combatants, while the chronicler mentions only knights.) And so what in official history qualifies as a joint battle of the Ruthenian nation against the threat from the West was in fact a conflict of Novgorod and Pskov with the Teutonic Knights and Swedes for spheres of influence on the Baltic shore. What is more, Pskov often acted as a rival of Novgorod and ally of the Teutonic Knights.

The later myth – created in the formative period of the state of Muscovy – of the first immortal victories over the “hostile West” has become one of the stereotypical elements of state-building “historical policy”, still vivid and brought up-to-date. The war of Muscovy against Poland, Livonia and Sweden as well as the associated confrontation of the Russian Orthodoxy with the “Latins” required the dual support of the emergent idea of statehood and nation: historical and religious, compatible with the notions and ways of thinking typical of those times. Therefore during the reign of Ivan III a “second embodiment” of Alexander Yaroslavich appears, namely “Alexander Nevsky”, and the “third embodiment” – “Saint Alexander” is brought into being under Ivan IV the Terrible. He was canonised in 1547, which was directly connected with the writing of the Book of Generations (Stepnaya kniga) inspired by the Metropolite Macarius. It was a history of the Ruthenian lands presented generation after generation (stepeni) of the dynasts from the Rurik family – the line of predecessors of the first crowned tsar of Russia. The authors were not very particular as to historical truth, for the priority was quite different: documenting beyond all doubt the sainthood of the greatest predecessors of the Most Enlightened Master of All Russia.

What could justify the sainthood of Alexander Yaroslavich – the protoplast of the Muscovy dynasts?

His bloody feats in defence of the Mongol system directed against the Christians opposing this system in their mass? His cruelty towards the Christians disobeying his orders? The opinion attested by authors of the chronicles about the “ungodly” reign of the Prince in the Christian Rus’?

The only logical justification is provided by the battles against the opponents of Ivan the Terrible from that time and consequently the relentless anti-Westernism of Alexander, both in his policy (previously based on the directives of the Horde) and in his attitude towards Papal Rome. Remarkably, in the same period advocates of fighting the Horde, their main goal regaining sovereignty (which also meant overturning a regime which was culturally alien to Christianity), made contacts with the Holy Roman Empire and the Papal Curia and directly negotiated with the Western neighbours, while Alexander Yaroslavich (whose political stance is judged by official historiography as the only correct one in the circumstances of that time) unconditionally accepted the rule of his tsar (as the Great Khan was then called in Rus’) and obediently realised his will. The servility of the Grand Duke descended into an absolute obsequiousness both personal (accepting the Mongol – pagan – ceremonies and courtly rituals, humiliating for a Christian) and political (relentless and cruel suppression of Ruthenian uprisings, savage treatment of the rebellious recorded by the chroniclers, keeping Russia in the heavy manacles of the system imposed by the Horde).

Striving for independence and associated hopes for Western support characterised not only parts of the elites but also urban patricians. Particularly influential and strong pro-Western groups were active in the republics of Novgorod and Pskov. In such circumstances emissaries of Pope Innocent IV visited the Grand Duke. The proposal to establish contacts and conclude a pact against the Horde was violently rejected by the Christian executor of the Khan’s will.

In opposition to the anti-Mongolian sentiments growing in the Christian Rus’, Alexander consistently followed the subservient oriental – anti-Western – option imposed by the Horde. The view of this prince as a defender of Rus’ against the German and Papal threat, which lingers in the official historiography, is not based on sources; it reflects the successive needs of ideology and requirements of propaganda.

The knightly orders did not plan to annex Russia (and if they did, their potential would have made it impossible), they had no vision of “Drang nach Osten” and “Catholicising Russia” (as is maintained in the History of Russia recently published by the Institute of Russian History of the Russian Academy of Sciences)[6]. They were interested only in the lands of the Baltic peoples and the Pskov-Novgorod area. So it was a conflict not with the entire Rus’, composed of separate principalities, but with the republics of Pskov and Novgorod. Therefore Alexander Yaroslavich – then the prince of Novgorod – defended not “the whole of Rus’” (which then experienced not the supposed “German threat” but the real Mongolian invasion) but the western borders of Novgorod and Pskov and their spheres of influence on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. And the young prince did not engineer anything new: he only continued a policy which existed before him and was to exist after him.

Another aspect of the still vivid myth of the “hostile West” is the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy.

Both were interested in fighting arm in arm with Russia against the threat coming from a civilisation alien to entire Europe – one that was belligerent and expansive. This was the case in Mongolian times, and was to be so too at the time of the Turkish might. The preserved contemporary records confirm that. And besides speculations and arbitrary judgements based on them, there are no material sources about the alleged temptations or even ominous plans of Rome against the Ruthenian Orthodox Church, just as there are no records showing that Alexander ever acted in the interest of the Orthodoxy.

The historical paradox of sanctifying and worshipping a ruler who splashed with blood the Christian Rus’, which did not want to be Mongolian Rus’, also persisted after the times of the bloody Ivan the Terrible. Brought up to date according to the changing needs of ideology, it was used by the system which established the Orthodox Church. Peter I, infatuated with the West, ordered (1724) the transfer of Alexander’s ashes to the new capital of the Empire. The worship of a staunch anti-occidentalist by a declared (and ardent) occidentalist is explained through the need of justifying (and hence implanting in the minds of the subjects) the “historical right” to the Baltic lands freshly taken from Sweden. Therefore, the day of concluding a peace agreement with the beaten neighbour (30 August 1721) was announced by the first emperor of Russia as the day of worshipping Alexander Nevsky. Hence his cult as a defender of Russian land, promoted and implanted in collective awareness through the “historical policy” of the state and the established Orthodox Church. The fourth embodiment of Alexander Yaroslavich thus came into being. In this phase of expansion of the myth the Alexander Nevsky Lavra was built in St. Petersburg – one of the four largest monasteries in the Empire. Soon after the death of Peter I (1725) his widow, Empress Catherine (née Marta Skowrońska) introduced the Order of Saint Alexander Nevsky as the highest decoration for military merit. In 1753, Peter’s daughter, Empress Elizabeth, commissioned a silver reliquary in which the mortal remains of the Prince were placed, and introduced an annual procession from the Kazan Cathedral to the St. Alexander Lavra as part of the religious calendar. In the early 20th century a street and a lane in the first capital of Russia were named after the Prince.

After the Bolshevik coup (1917) the pantheon of standard figures from the tsarist times turned into a panoply of revolutionary heroes, and from the 1930s it regained the favours of the totalitarian regime because of the ideological requirements of the Stalinist superpower aspirations. When the internationalist slogans of world revolution were replaced by patriotic slogans of nationalist-imperialist socialism, the Prince from an “alien class” was put back on the pedestal as a providential figure, a heroic defender of the country and conqueror of the “German dog-knights” (psy rytsari)[7]. In 1938 Sergei Eisenstein made the world-famous film Alexander Nevsky. According to the 1930s ideology renewed by Stalin, the screenplay (originally entitled Rus’) presented a traditional version of official history, with the traditional image of the main character and the traditional version of his achievements. The eminent historian Mikhail N. Tikhomirov described the plot as “a travesty of history”[8]. Shelved as a result of the unexpected alliance between comrade Stalin and Parteigenosse Hitler, the film was first shown in 1941 after the Nazi invasion on the USSR and awarded the Stalin Prize. In 1942 the Order of Alexander Nevsky was introduced as one of the highest military decorations. The money collected by the Russian Orthodox Church then financed the production of airplanes for a squad named after the Prince. In the post-war era a number of monuments to him were unveiled, and streets in various cities were named after him.

The official cult of Alexander Nevsky persists until today. Reinforced in the collective awareness by textbooks, continued by the stereotypes of official historiography and promoted by the state-building ideology, it is still shaping social memory and channelling the national awareness. And as an example of the unofficial, independent and free historical, national and civic thought one can quote the following judgement: “It is a disgrace of Russian historical awareness, of Russian historical memory, that Alexander Nevsky has become an unquestionable object of national pride, it has become a fetish, it has become a standard not of a sect, not of a party but of the nation whose fate he misdirected so cruelly. […] Without a shadow of a doubt Alexander Nevsky was a national traitor.”[9]

The logic of this harsh and unambiguous judgement becomes understandable when we realise that in that period (right after the Mongolian invasion) the Ruthenian plenipotentiary nominated by the Horde, repressing political opposition and numerous insurrectionary forces, made a clear choice between the East and the West in favour of the former, that is a civilisation which was alien in terms of history, politics, religion, culture and customs. This meant that the tradition of the Kyiv-Novgorod Rus’ – its history, its culture (including political culture), the very awareness of sovereign being and the essence of the felt identity – was definitively interrupted, deliberately and cruelly destroyed. Consequently the direction of development of the whole of Eastern Europe was radically changed. It inevitably led to the emergence of the Mongolised Moscow despotism, which acquired its perfect shape under Ivan the Terrible. As the contemporary thinker Georgi Gachev aphoristically puts it, Rus’ became a victim of Russia.

The Mongolian face of the Moscow regime

The story of mythologizing the figure and the actions of Alexander Yaroslavich (and by no means just of him) reflects both the history and the very essence of the Russian system of power[10]. Violent and cut off from its own nation in its aloofness, it created false idols for the people, so that by worshipping them, they worshipped the regime itself, blindly succumbed to its authority, obediently believing in its principles as the highest values. This manoeuvre turned official violence into the patriarch’s caring about his children[11], its savagery into harsh but just fatherly punishment and its cruelties into the necessary condition of survival and proper functioning of the family[12], that is also the patrimonial state[13]. This is how the Moscow statehood from the very beginning of its existence justified and legitimised its method of executing power following from its Mongolised essence, disguising its true identity through creating its virtual image in the awareness of the subjects (also with the help of the increasingly enslaved Orthodox Church)[14].

The cruelty of the Horde translated into the cruelties of its Moscow vassals and their ruthlessness towards the rebellious population of the Christian Rus’. For the people the Horde was hostile and alien, for the vassals it was a friend and kin[15].

The Story About the Invisible Town of Kitezh survived to our day: on hearing that the Mongols were approaching, the inhabitants prayed to the heavens, asking to be saved from rape and humiliation. God answered their prayers: within sight of the stunned invaders, accompanied by bell-ringing and religious chants, the town was hidden by the waters of a lake. According to legend chanted prayers and bell-ringing can be heard from the depth of the lake, which really exists.

Some scholars believed that in the original version it was not the Horde but the Moscow army which arrived. The government later suppressed this story.

The legend is still present in the Russian awareness and folk culture. In his documentary Bells from the Deep: Faith and Superstition in Russia (1993), the well-known German director Werner Herzog filmed people creeping on ice in the belief that they would see a town hidden in the depths.

A paradox of the religious-patriotic mythology: the conqueror of the Horde in the shadow of the suppressor of Rus’

The terror of Ruthenian Christians, Alexander Yaroslavich, isolated in his own family (his brothers Andrei, who found refuge in Sweden, and Yaroslav, as well as his son Vasily, were in opposition) was the first perfect embodiment of an absolute settlement with an invader. This eminent architect of political Mongolisation of Russia, a rigorous executor of the Khan’s orders, the implementation of which resulted in the alienation of the Ruthenian regime from the Ruthenian population, thanks to the government and Church ideology of Moscow overshadowed the first conqueror of the Horde, Grand Prince Dmitry (1359–1389). This genuine hero of the struggle for Russia’s dignity, the commander who dismounted his horse and fought like an ordinary warrior, motivating by his own example and enhancing the belief in victory in the hitherto unconquered enemy, after the great Battle of Kulikovo on the Don (1380) acquired the sobriquet “Donskoy”.

Dmitry Donskoy was proclaimed saint only in 1988. Why was the Orthodox Church, which had so quickly shown its favour to the bloody suppressor of Christian Rus’, so tardy in recognising the virtues of the brave Prince, who gained the blessing of Sergius of Radonezh himself (perhaps the greatest figure in the Old Russian line of saints) as well as widespread recognition among his contemporaries and later generations? The most likely reason was the pronounced conflict between the Grand Prince and the Ruthenian Church hierarchy, triggered by his decision to place Mikhail (Mityai), his confessor as well as a high official (guardian of the Grand Prince’s seal, counterpart of the Western chancellor), on the metropolitan throne. Thus, in his relations with the Church this ruler was ahead of the historical time: only after the Russian statehood took shape and was solidified – that is almost a century and half later – did the Russian Orthodox Church start to succumb to the Russian state, embodied by the autocratic tsar.

Conclusion

The use of history by actors external to it means depriving it of its status as a scientific discipline, for it is turned into an ersatz, a kind of applied science, that is a craft rather than an instrument of knowledge. Each scientific discipline aims at objective knowledge and history (as every branch of humanities), when subject to any pressure or in any way connected with an actor external to it, creates not objective knowledge but a false awareness, dependent on and subservient to strictly non-scientific factors. A telling example of this is history textbooks written in various periods, or even in the same period but representing various ideological or party-political options.

Such history, reinterpreted or even manipulated, ceases to be a science, for science is identical to itself. This identity is constant and unchanging against the fluid socio-political or party-political reality. And each manipulated history, serving the purposes defined by actors external to it, changes its identity with every change of the ideological and political agency calling it into being. Hence the question: does such history serve its prescribed goals in the long term, even if they are formulated as ethically noble and patriotically correct?

Subordinating history to goals (the content of which changes in line with changes at the highest echelons of power) leads to some goals (“correct” from the point of view of holders of spiritual and political power) being ennobled and glorified and others (“incorrect” ones) obfuscated, disparaged or even condemned. But the “correct” and “incorrect” goals may trade places depending on the changes in the ruling ideology. Such continuously distorted vision of the nation’s history cannot shape civil society and a fulfilled personality. A civic attitude cannot be enforced through legal sanctions or restrictive measures. But people can be educated to it through history taught non-ideologically, that is through its own lessons – and not through lessons of an ideologically reinterpreted and politically straightened vision of the country and nation. Hence a completely rhetorical question: perhaps it is history itself as a science which should shape worldviews, government programmes, party-political doctrines in the 21st century, after the painful experiences of the ancient and not so ancient past?

“History is not a teacher but a supervisor of life – claimed our great historian Vasili O. Kluchevsky a century ago – it teaches nothing but only punishes for not knowing the lesson”[16], which is “an instrument of self-mending”[17].

Historia est magistra vitae has been present in the collective memory since primordial times. But the constant practice of bending history for the particular purposes of this or other reason of state, a system of power or party propaganda, still results in the fact that both the regime and the people blindly and obediently following its directives keep stepping on the same rake. This happens because the false consciousness generated by manipulated history is deprived of critical thinking shaped by scientific history. The problem is that real history reinterpreted in accordance with successive needs loses not only its real dimension but also the large (and therefore instructive) perspective proper to it, replaced by a blinkered view. By its very essence and its cognitive limitations it generates ahistorical thinking, leading to a vision restricted by stereotypes and prejudices born in the ancient and recent past. And this not only cuts us off from 21st-century modernity but also leads us back into the blind alley of old traumas, mistakes and crises.

In such an antique way contemporary “historical policy” makes it impossible to draw lessons from history, which according to the ancient predecessors of today’s Europeism is supposed to be magistra vitae.

Translated from the Polish by Tomasz Bieroń

***

[1] “Kupię jej ten kwiatek” (I will buy her that flower), Lech Wałęsa interviewed by Janina Paradowska, Polityka 2012, nr 14, s. 15.

[2] Ocherki istorii SSSR. Period feodalizma IX–XV ww. V 2 chastiakh, Moskva 1953, part 1, p. 854.

[3] Ibidem, pp. 848, 851, 852.

[4] Istoria Rossii. S drevneyshykh vremen do kontsa XVII veka, Moskva 2000, p. 251

[5] Novgorodskaya pervaya letopis starshego i mladshego izvodov, in: Polnoye sobraniye russkikh letopisey, Moskva 2000, t. 3, s. 78.

[6] Istoria Rossii. S drevneyshykh vremen do kontsa XVII veka, Moskva 2000, p. 251

[7] By the way, it is another invention of “historical policy”, which used the German scare when the moment was propitious. This phrase, which has come into common usage thanks to the religious-patriotic ideology and state-building mythology, is not to be found in the historical records of old Rus’.

[8] Mikhail N. Tikhonov, Drevnaya Rus, Moskva 1975, p. 375

[9] Mikhail M. Sokolski, Niewiernaja pamiat´. Gieroi i antigieroi Rossii. Istoriko-polemiczeskoje essie, Moskwa 1990, p. 193.

[10] It also characterises very well the current of Russian historiography subservient to the regime, called the “national school” (gosudarstvennaya shkola).

[11] Hence the popular description of the autocrat, “daddy tsar” (tsar´ batyushka).

[12] Responsible for all iniquities are strangers, those from outside the family – “boyars”. The daddy tsar does not know it, but when he finds out he will punish the guilty ones and justice will return.

[13] Hence the popular description “Mummy Rus’” (Matushka Rus´). From its beginnings until today the Russian system successfully – through education, propaganda, official scholarship – identifies in the social awareness the native land with the government, the homeland with the political system, the country with the regime, patriotism with adulation of the head of state.

[14] This historical experience in manipulating social awareness was adopted – and ingeniously developed thanks to the huge propaganda apparatus – by the Bolsheviks, using the same patrimonial-familial vocabulary: “Grandpa Lenin”, “our father, teacher and friend Stalin”, CPSU – “our family party”, USSR – “a family of nations” or the Country of the Soviets – “Mother Homeland”.

[15] This was a typical expression of the political thinking of the Ruthenian power elite, reflection of the contemporary notions of the community of local interests and supralocal reason of state. An example of analogous conceptions in the West (bearing in mind the differences in civilisation and culture) was the attitude of the vassals towards the lord, the vassals’ districts to the suzerain’s district. A significant and fundamental difference was that in the West these were legal-political arrangements between representatives of a common civilisation, while in the Mongolian Rus’ it was an absolute subordination by conquered representatives of one civilisation to the demands, interests and will of culturally alien conquerors, with all the consequences in the sphere of politics, economy, culture and national identity itself.

[16] Aleksandr Janov, Zagadka nikołajewskoj Rossii 1825–1855, Moskwa 2007, p. 11.

[17] Wasili O. Kluchevsky, Soczinienija, Moskwa 1958, t. 3, p. 296.

Copyright © Herito 2020